With a brand new German translation of the Hail Caesar rulebook just out, and the hugely detailed supplement Age of Caesar hitting the stores this weekend, we decided to revisit these designer’s notes from the author of said tome, Rick Priestley…

Rick: This time round I thought I’d talk a little bit more about the Hail Caesar game itself – both in terms of the mechanics and what is sometimes called ‘games philosophy’. I’m not too sure whether ‘philosophy’ is not too grand a title for the kind of thinking that goes into a wargame – Wittgenstein I ain’t – but we can certainly take a look at some of the ideas and ambitions that have informed the development of Hail Caesar over this last year.

Hail Caesar is – as I’m sure you all know by now – based very firmly upon our Black Powder wargame. Those who already own a copy of Black Powder will therefore have a fair idea of what to expect – and throughout this article I will be making comparisons between the two games. For the benefit of those who might not be familiar with Black Powder I’ve tried to give a brief overview of the mechanisms in their basic form.

They have both been developed amongst our own gaming circle, for our own use, and to play the kind of games we enjoy.

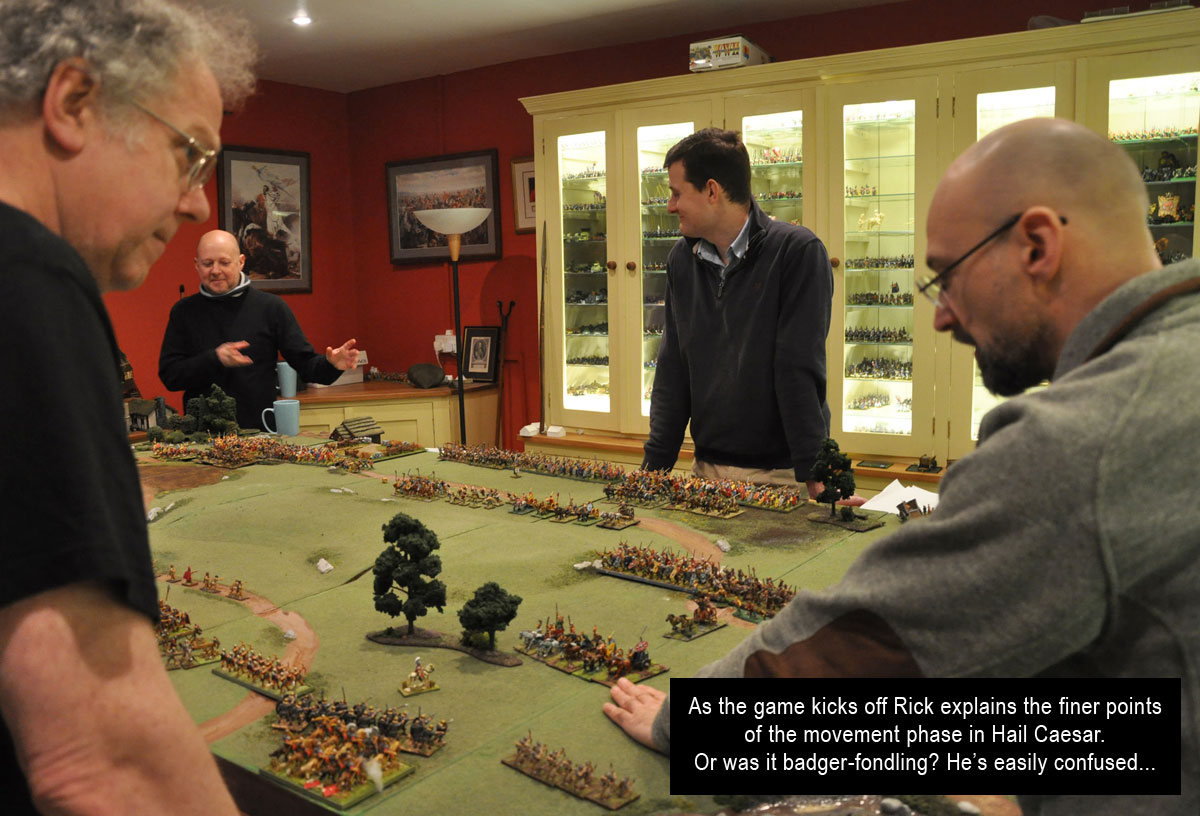

Black Powder and Hail Caesar share a common approach to gaming – they have both been developed amongst our own gaming circle, for our own use, and to play the kind of games we enjoy. By making these rule sets available more widely we hope for no more than to introduce others to a style and type of gaming that anyone can participate in should they wish to do so. In presenting the rules for publication we have endeavoured to carefully explain how they work, and how players might choose to expand and develop the core ideas for themselves, but we have not otherwise compromised the central tenet of the game – a game played between friends in the spirit of comradeship and entertainment. Of course, at no point did anyone ever sit down and write a ‘brief’ for our games. They simply evolved over time as a result of ideas and enthusiasms amongst the group. But if a brief had been written it might have looked like this:

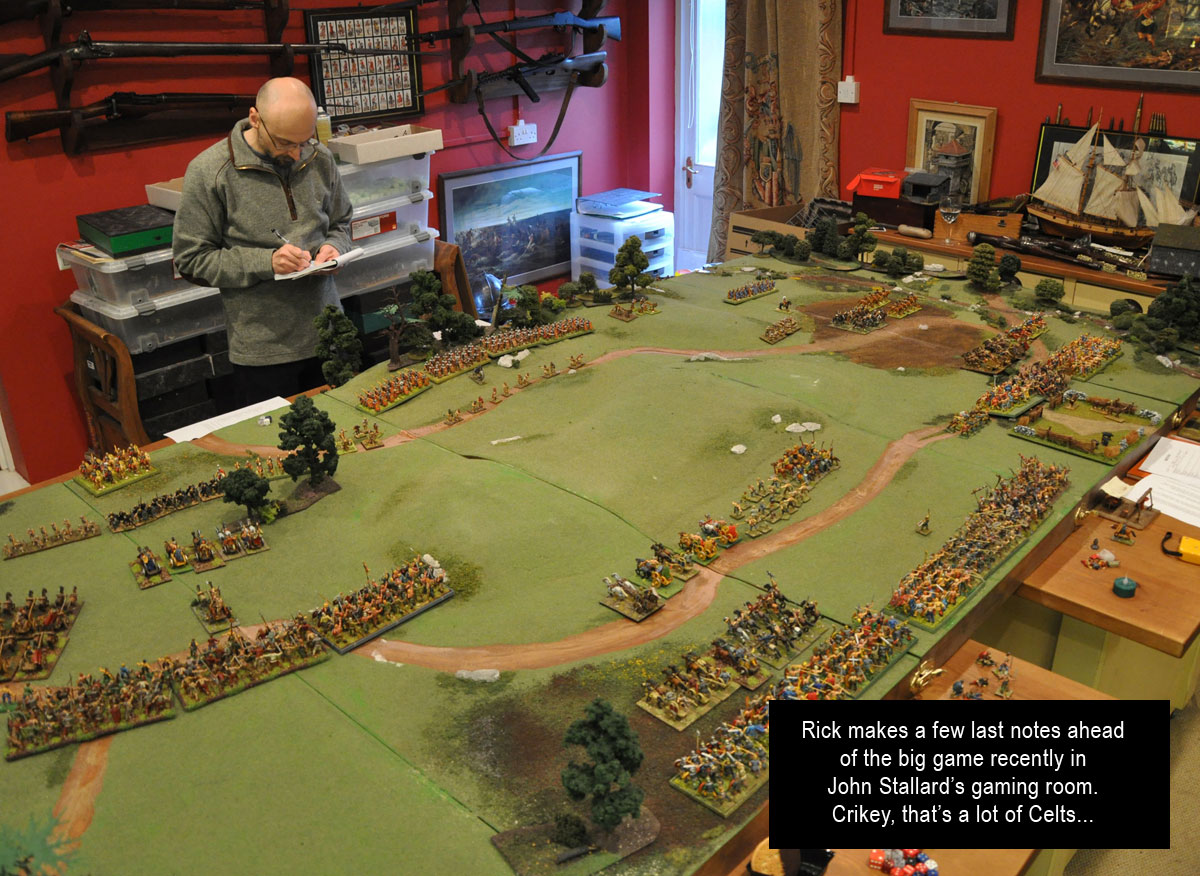

* Our game must start and finish over an evening allowing sufficient time for the consumption of curry – the table, armies and scenario would ideally be prepared beforehand – though don’t count on it – especially round at John’s.

* Our game must easily accommodate two or three players a side – although it must be possible for a single player to control an entire army if need be – should Little Steve have so exhausted himself lion taming that he falls asleep on the sofa – for example.

* The game must allow for our existing collections of models, which are based every which way and comprise units of differing sizes – but are all 25mm or 28mm ‘scale’ – except for Rick’s 10mm which we prefer not to dwell upon.

* The armies available are a fair size – well frankly huge in the case of Alan’s Napoleonic collection – and the game must commonly facilitate big battles as well as the occasional smaller action.

* The tabletops available vary – none smaller than 8 feet by 4 – but the chief battlefield is 12 or 14 feet by 6 necessitating the inclusion of at least one player with very long arms – Jervis being a prime example of the breed. All the tables comprise rolling terrain modelled with rises and depressions, rivers and roads, and with plenty of scenery representing villages and towns, fields, orchards and areas of cultivation. This does mean that the exact placement of units can get a bit vague.

* As well as providing for our regular group the game must take into account occasional guests and visitors who may want to pitch in and take control of part of an army.

Our players are also looking for an enjoyable, social evening – they are not looking to spend ages cross-referencing charts, totting up factors, and micro-adjusting movement.

Those are probably the main drivers behind the development of our rules. Of course, the tastes and preference of our comrades are a major factor too – and here we must bear in mind that most of us are friends because we have at some time or another been workmates at Games Workshop. So, as a group we have a relatively high proportion of professional games designers, sculptors, model makers and artists – including the owners of at least four wargames hobby businesses. Needless to say – everyone has their own ideas about what makes a game enjoyable – but it’s reasonable to say that all of our players are primarily interested in a social game in which the quality of the models, terrain and curry are of at least equal importance to the rules themselves. The aesthetics of the wargame are a major part of its appeal – and the rules must produce games that look attractive and which ‘tell a story’ as they play out. And that story should be entertaining and dramatic – at least worthy of repetition during the post-battle pint in the local pub.

In terms of how this translates into game mechanics, it should be pretty obvious we need a game that plays fairy quickly, as we aim to complete what is probably a larger than average battle over the course of a single evening on what is a big tabletop by most people’s standards. Our players are also looking for an enjoyable, social evening – they are not looking to spend ages cross-referencing charts, totting up factors, and micro-adjusting movement. So, our game is designed to crack along at a good pace, and uses multiple dice rolling as its prime mechanic rather than single rolls with multiple factors, thoughtful card play, or mechanisms that require a great deal of careful calculation before actions can be taken. No criticism of games that employ these techniques is implied, all of these mechanics are good in their place, but for purposes of our game it is preferable to stick to multiple dice rolling with minimal modification.

To achieve our goal of rapid and decisive movement we allow for relatively long moves and we permit units to make up to three moves in their turn.

In broad outline both Black Powder and Hail Caesar play in the same fashion. Each side takes a turn alternately completing all of its movement, then shooting and finally resolving any hand-to-hand combats before the opposing side takes a turn beginning once more with movement.

Although play is alternate as described, the side that is not taking the turn has the opportunity to move in some situations (to countercharge or evade for example), and to shoot (with traversing or closing shots), and to fight in hand-to-hand combat. When casualties are inflicted it is also necessary for the side that suffers them to take morale checks (effectively saving throws) and also to take break tests where required.

These interactions ensure that all players remain involved in the game even when it isn’t their turn. Hand-to-hand fighting also includes a certain amount of post combat movement when losing troops retreat, allowing the victors to press home their attack or consolidate their position – all of this can potentially result in units form both sides moving regardless of which side’s turn it happens to be.

Orders

To achieve our goal of rapid and decisive movement we allow for relatively long moves and we permit units to make up to three moves in their turn. Whether they move at all, and how far they move, depends upon the result of a test made against the command value of their accompanying leader or commander.

Each commander controls a brigade or division comprising one or more separate units (for example four infantry battalions). Often a player will take responsibility for one division of troops, with the side represented by three or four players in all. If the army is especially large or players are in short supply each player controls several divisions.

To move any unit under his control the player first nominates the commander model that will ‘give the order’, he then explains what he wants the unit to do – in real world terms as far as possible – and then he rolls two dice adding the scores together to determine if the order has been successfully received and understood.

Most commanders have a value set at 8 meaning the player must roll 8 or less on two dice to issue a successful order. If the roll is 8 or 1 less the unit has one move in which to try and complete its order, if the result is 2 less the unit has two moves, and if 3 less or more the unit has three moves. If the result is more than 8 the unit fails to move at all, although in some situations units are allowed a single move even when their order is ‘failed’.

Units are always obliged to fulfill their order in so far as possible – no hanging back just because you wanted two moves but have rolled only one! This is the principle means by which orders are issued and troops moved in our games – and it allows for rapid movement as well as occasional bottlenecks and frustrations as orders go awry or troops fail to move at all.

Move

As we have said the move distances are quite long – though less so in Hail Caesar than in Black Powder. In Black Powder infantry move 12” at a time, whilst in Hail Caesar they move 6”. In Black Powder cavalry move 18”, where in Hail Caesar they move between 6” and 12” depending on their type. This emphasises the differing character of warfare with the shorter moves in ‘ancients’ tending to place more importance on holding a line and keeping supporting troops nearby.

To compensate for this to some extent there are more ‘automatic moves’ in Hail Caesar than are allowed in Black Powder. These cover situations where a unit can move either without an order or, in some cases, allow a unit to move once even where its order is failed.

For both of these games we’d happily recommend players adjust the move distances given to suit their own tables if they are significantly smaller than our own. Having said that, we have played Hail Caesar across a 4 foot wide table without feeling the need to reduce movement distances – being content to ensure no troops were deployed within potential charge range of enemies at the start of the game.

Shoot

Shooting is an important part of Black Powder and much less so in Hail Caesar. In Black Powder volleys of musketry will often stop an enemy formation in its tracks by disordering it. Although shooting is an important part of ancient warfare it is much less likely to be decisive. Hail Caesar therefore treats ranged fire and any resulting disorder a little differently.

In Hail Caesar ranged attacks represent not just longer ranged missile fire with bows, crossbows and slings, but also short ranged exchanges of thrown missiles as well as skirmishing either by troops in open order or, where appropriate, by bodies moving beyond the main formation. Almost all units have been given a short ranged ‘shooting’ ability to represent this, including most close-fighting infantry such as Roman legionaries and Greek Hoplites (though not pike-armed phalangites… should you be wondering).

This range is a mere 6” but this is entirely adequate to allow for an exchange of missiles prior to a head-to-head clash or ‘soft contact’ between troops fighting in looser formations. All units therefore have a short and long range ‘attack value’ equivalent to a number of dice: usually 3 at short range and either 3 or 0 at long range depending upon armament.

When making ranged attacks the unit rolls the number of dice indicated and scores of 4 or better are required to inflict ‘hits’. A few modifiers apply – and in the case of Hail Caesar these modifiers tend to push the odds down slightly compared to Black Powder. In Hail Caesar any 6’s rolled when making ranged attacks result in a break test rather than causing disorder automatically as they do in Black Powder.

Hail Caesar also has separate break test charts for missile fire and hand-to-hand combat, with disorder being a potential result of this test in both cases. In both games disordered units are unable to move in their own turn and also suffer a penalty for shooting and hand-to-hand fighting so this is a significant penalty.

Casualties

When units suffer casualties these are recorded by whatever method the players prefer. Our own habit is to use model casualties – though we often employ a distinctly coloured dice to indicate casualties whilst they are inflicted as this saves time. We do not remove models from the units themselves, and this is one of the reasons why the exact basing style of our troops isn’t terribly important – there being no need to remove individual models as casualties during the game.

Although units can suffer any number of casualties throughout the course of a battle the maximum number that is recorded in Hail Caesar is usually 6 if the unit is of a regular size. This is double the value in Black Powder where units can normally take 3 casualties, and the difference reflects the importance of prolonged combats in the ancient game.

Of course, this also means that the effect of missile fire is relatively less in Hail Caesar than Black Powder, something we felt was only proper given the differences in weapon technology and tactics. Casualties inflicted in excess of 6 are not carried over from one turn to the next but become negative modifiers on any break tests the unit is obliged to take. Once a unit has its full quota of casualties it is considered ‘shaken’ which prevents it deliberately engaging in hand-to-hand fighting and imposes a penalty on the unit’s shooting and combat dice.

Hand To Hand

Units also have two different values for hand-to-hand combat: a clash value which is used in the first round of any combat, and the sustained value which is used at all other times. In both cases these values are the number of dice rolled varying from 4 or 5 for light troops to 7 for heavy infantry and 8 or 9 for heavy cavalry.

The basic mechanic is the same as for shooting – roll the number of dice indicated and all results of 4 or more score ‘hits’. The unit that has been attacked then rolls one dice for each hit it has suffered and its morale holds on scores of 4 or more effectively negating that hit.

All unsaved hits are then recorded as casualties onto the unit. This is a very simple mechanic – multiple dice rolling – but very effective in terms of creating moments of tension within the game and as a method of balancing play. Both sides fight in hand-to-hand combat regardless of which side’s turn it is, and the side that scores the most casualties wins the fight.

The losers must then take a break test, rolling two dice against a chart, which can result in the unit holding its ground, retreating or breaking altogether in which case it is removed from play entirely. In Hail Caesar, unlike in Black Powder, there is also the potential for a unit to break automatically without recourse to a break test if is receives enough casualties in one go.

Anyway – that’s a very generalised summary of the game’s basic mechanics and some of the differences that mark Hail Caesar from its Black Powder predecessor.

Starter Set

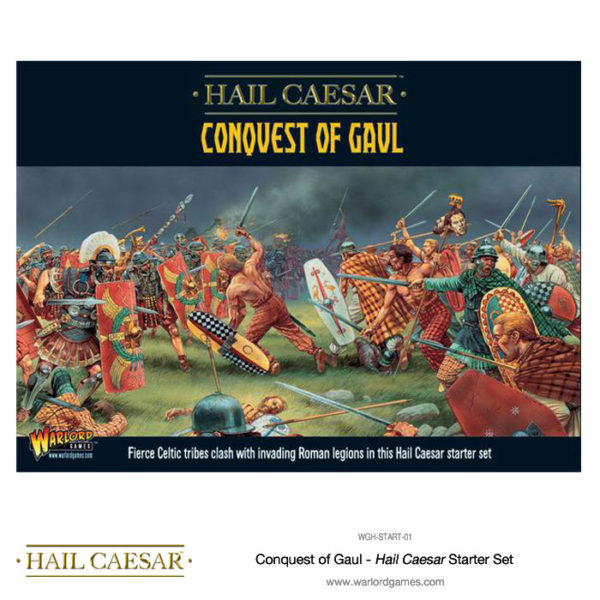

The Conquest of Gaul starter set is the perfect entry into ancient battles, pitching Roman Legionaries against a horde of Celts – and it’s now available with either the English or German rulebook inside:

Rulebook

Alternatively, grab the rulebook separately – again in English or German – along with the free exclusive model of Centurion Titus Aduxas:

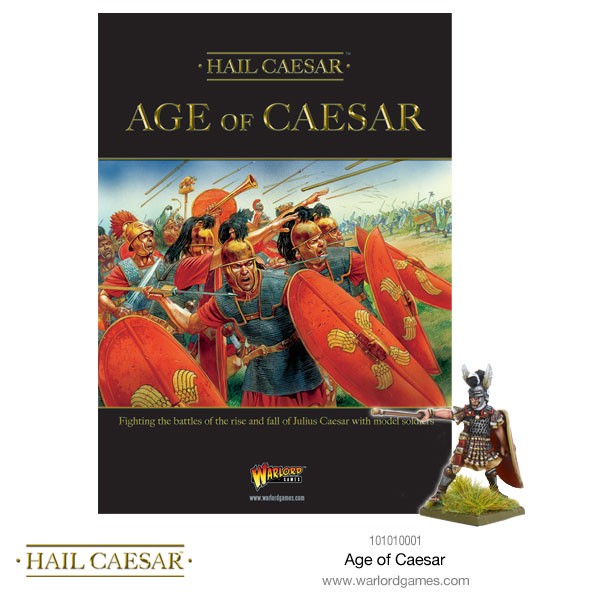

Add a Supplement

Once you have the rules (or even before if you so wish) you can zero in on the force or period of conflict that interest you the most, be it Ancient Britons, early or late Roman, Germanic tribes, or Celts. The Warlord range has grown vast and you’ve plenty of choice to peruse at your leisure. Our latest supplement of course introduces us to Caesar and his numerous conflicts and is packed with gorgeous and inspiring models and scenarios for you to reenact: