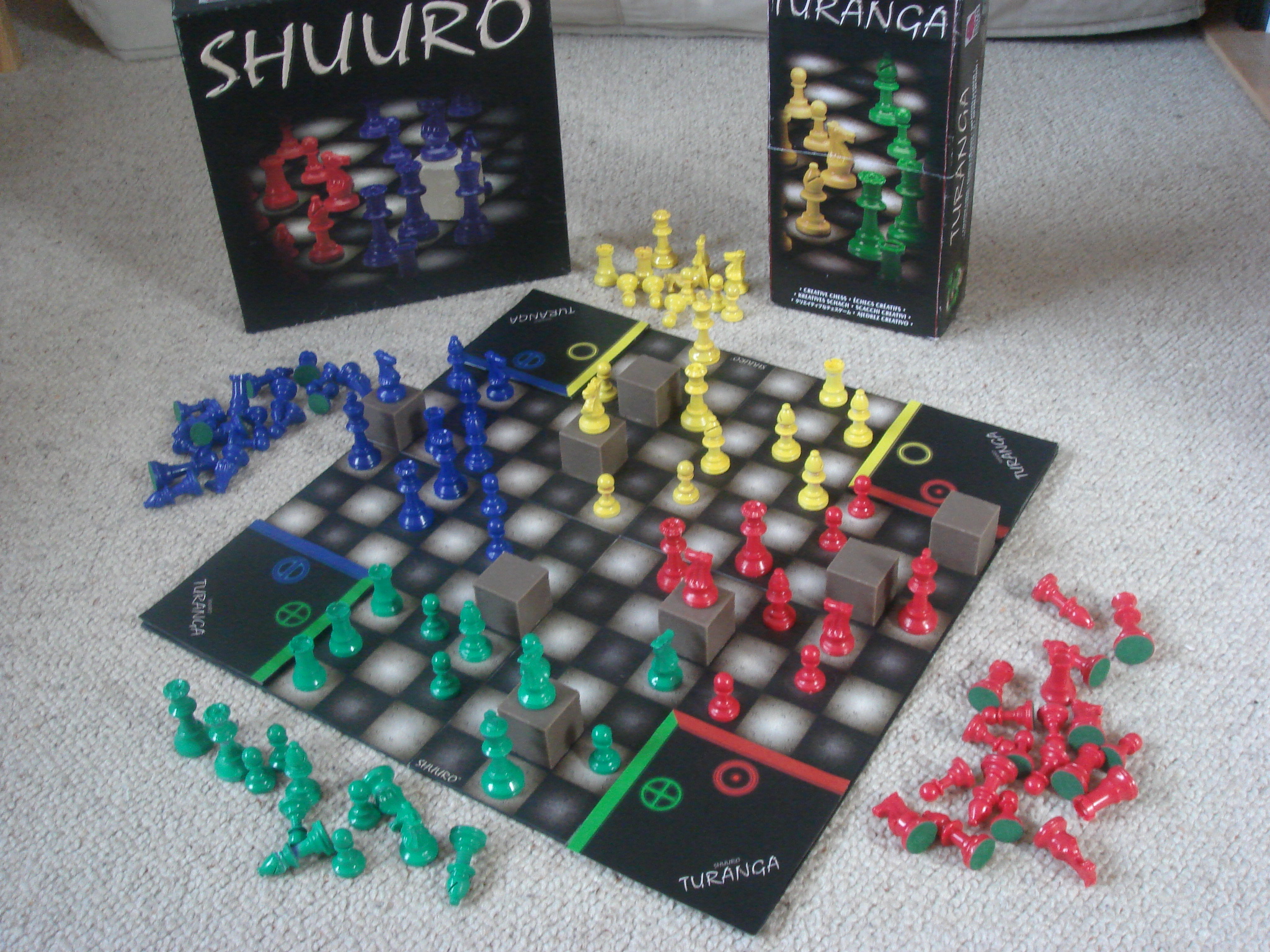

Renowned Games Designer Alessio Cavatore has been a busy man since leaving Games Workshop. Not only has he been helping us with our forthcoming Ancients rules but he’s also founded his own company, River Horse Games, to produce boardgames. His first offerings are an intriguing and innovative take on Chess called Shuuro and Turanga.

Read below to find out all the details…

PER ASPERA AD ABSTRACTA

The Making Of Shuuro

By Alessio Cavatore

To set the scene…

It all began so many years ago, when I was just a kid, I had a huge collection of toy soldiers by Airfix, Esci, Atlantic – hundreds and hundreds of little plastic soldiers that span all periods but mostly were from the Second World War.

At first I used them mostly at our home on the seaside (Noli, on the Italian riviera). There, on the beach, I built fortifications out of sand and then deployed the toy soldiers and began the battle by throwing small pebbles at them. To this day, the sands of that beach still occasionally return the occasional toy soldier…

Then I discovered chess, which my dad taught me during the holidays in Lillaz (in the Alps). I still have the first chessboard he gave me as a present. I still remember the smell of the wooden pieces and their wooden box…

Next it was wargames, in the shape of a great series of old books – Battlegame Books by Andrew McNeil. Each one of these books had a theme (WWII, Medieval knights, space pirates and so on) and in the first half it presented some history, information and great pictures, while at the back it had four wargames each, with cardboard cut-outs and simple rules.

And that’s when I happened to notice that the parquet of my bedroom at home in Turin) was just perfect for wargaming – it had a chequered motif!

So I began a period of intense gaming (solo, of course!), when I deployed my hundreds of toy soldiers onto the floor and then moved them on that large square grid. Combat was resolved with dice, trying to use the rules from the aforementioned books. Soon, however, I started realising that those rules were not written to handle huge formations of toy soldiers on a large board (the floor), with terrain (books and such like). So I started writing my own rules. Simple stuff, of course, but it did the job.

So I began a period of intense gaming (solo, of course!), when I deployed my hundreds of toy soldiers onto the floor and then moved them on that large square grid. Combat was resolved with dice, trying to use the rules from the aforementioned books. Soon, however, I started realising that those rules were not written to handle huge formations of toy soldiers on a large board (the floor), with terrain (books and such like). So I started writing my own rules. Simple stuff, of course, but it did the job.

I’ve spent countless hours making larger and larger battle, introducing vehicles (all clearly the wrong scale, and often the wrong period, but who cared!) and refining my rules, and soon realised that my wargaming style had severe limitations: a mum intent on sweeping the floor or the playful house cat were only some of the dangers faced by my glorious armies…

Eventually I bought my first wargame in a box: Avalon Hill’ s Africa Korps. From there it was more games by Avalon Hill, International Team, Milton Bradley and even the more mainstream Risk, which of course allowed me to ‘ train’ some friends, like Cristiano Delle Case, and slowly bring them to the Dark Side of wargaming.

It was just about then that, while roleplaying with miniatures, I was exposed for the first time to the game that was to become such an important part of my life: Warhammer Fantasy Battle. It was love at first sight and it led to a mad campaigning season that saw me in the end winning the Italian tournament in 1995 (which, it has to be said, was a very small affair at the time), and eventually landed me a job at Games Workshop, first as a translator, and then as a games designer.

After many years of war gaming with miniatures, both fantasy/sci-fi and historical (with the likes of the Perry twins!), I finally decided to have a stab at designing my very own game.

Hopefully this little autobiographic excursus has helped to frame the background from which the concept of Shuuro was born.

Minimalistic Wargaming – the birth of a concept

Amongst the many aspects that I find fascinating with wargames, one of my favourites is the picking of the army list. I normally spend hours upon hours choosing my force. I love the meta-game that goes on in your head when you prepare for battle. It’ s a bit like in roleplaying, where one of the things I love the most is generating a new character. All of that potential, all of that planning ahead, daydreaming about the strengths and weaknesses of the character, about all of the situations when his many abilities will come in useful.

Wargames do that by assigning a points value to each type of troop in the game. Some are more powerful, and cost a lot of points, others are weaker, and so they are cheaper. The choice of whether to rely on a multitude of cheap, low-level pieces, or to instead field a small elite army of few super-powerful pieces, is always an intriguing one. Often there is no right and wrong answer, it is all about the terrain of the battlefield where the engagement is going to happen and the type of opponent that the army is going to face.

So, roughly ten years ago, I was struck by the realisation that the points value system was something I had seen already, in a game that is a lot more mainstream than wargaming – chess! I remembered my dad teaching me the relative value of chess pieces, as part of explaining about exchanges: “A Knight or Bishop is worth three Pawns, a Rook is worth five, a Queen is at least as good as a Bishop and a Rook together…” It was quite obvious that this was the same concept of points system used in wargaming: the better a piece is, the more points it costs!

And chess, after all, is still very clearly a simulation of a battle, albeit a very abstract one. The next step was a somewhat obvious question that came quite strongly to my mind: if I was given the chance of changing the composition of my chess set by spending points to have different pieces at the start of a game, what would I do? How would I spend my points?

At the beginning this was just a subject for conversation with some of my more chess- minded friends, but in a little while I started to think about making more of it, maybe designing a game based on this simple principle.

Before I began, I had a good look around on the net and in the few books I could find for an existing game or chess variant that used this simple principle of assigning points to the pieces and letting the player choose their own army, but, to my amazement, I couldn’t find any. Surprised and delighted that the idea seemed like an original one, I set myself in motion and so the first prototypes of Shuuro was born.

First, the battlefield

Initially, I experimented on normal chessboards, using the classic relative points of the chess pieces, but I soon found that if I wanted to spend more points, to field larger armies. One side effect of fielding larger forces was that these armies were feeling a bit too crammed, squeezed in by the size of the board. By having two large armies facing off, the space in between them was often not even enough to deploy all of the pieces – I needed a bigger board! I made a few larger boards, and I loved the extra freedom offered by a wider and deeper gaming space.

One of the effects I soon noticed, however, was that a large board meant that ‘ long’ pieces (i.e. those that are capable to move of any amount of spaces, like the rook, bishop and queen) were getting proportionally better, the larger the board. This is easily explained by thinking of how many squares are controlled by one such piece placed near the centre of an 8×8 board, and how many are instead controlled from the centre of a 12×12 board. On the other hand, the ‘ short’ pieces (i.e. knights, pawns and the king) did not improve at all, as the length of their moves is fixed. My first thoughts when presented with this problem was to simply change the proportional value of the pieces, making pawns and knights cheaper, but while I had no qualms downgrading the pawns, it seemed somehow wrong to do the same with the knights. You see, I love knights in normal chess and I love the balance of power existing between pieces as different as bishops and knights, so it felt wrong to undermine this intriguing element of the game. I needed something to limit the increased power of ‘ long’ pieces and to benefit the abilities of the knight.

One of the effects I soon noticed, however, was that a large board meant that ‘ long’ pieces (i.e. those that are capable to move of any amount of spaces, like the rook, bishop and queen) were getting proportionally better, the larger the board. This is easily explained by thinking of how many squares are controlled by one such piece placed near the centre of an 8×8 board, and how many are instead controlled from the centre of a 12×12 board. On the other hand, the ‘ short’ pieces (i.e. knights, pawns and the king) did not improve at all, as the length of their moves is fixed. My first thoughts when presented with this problem was to simply change the proportional value of the pieces, making pawns and knights cheaper, but while I had no qualms downgrading the pawns, it seemed somehow wrong to do the same with the knights. You see, I love knights in normal chess and I love the balance of power existing between pieces as different as bishops and knights, so it felt wrong to undermine this intriguing element of the game. I needed something to limit the increased power of ‘ long’ pieces and to benefit the abilities of the knight.

The answer came to me from the same place were I started – wargaming. In war games, the table is littered with elements like hills, woods, rivers and buildings, all of which affect how the units deployed in them perform. And, more to the point, as these pieces can be moved to represent an infinite number of different battlefields.

I decided that, in the same way as Shuuro’ s armies were to more closely represent real armies, that are never exactly the same as the enemy, its board was going to more closely represent a real battlefield, which is almost never a flat and featureless field. In real battles, terrain is a vitally important element, one that can completely influence the balance of power between opposing forces, from the cliffs at the Thermopylae, to the walled farmsteads on the field of Waterloo, to the jungles of Viet Nam. And so the plinths were born.

I literally imagined that some squares of the board emerged to form impassable obstacles, blocking the movement of long pieces and making the knights’ jumping ability more useful.

It was only later, while playtesting, that one of the players landed a knight on top of one of the blocks, joking that it looked like an equestrian statue. And there it hit me – there was a way of making the knight even better, to further address the imbalance in power with the bishop. If knights could not only jump that blocking element, but also occupy it, they would become almost invulnerable in such position, as only an enemy knight could reach them there! And I loved the idea that in a battle only some troops are suitable for taking defensive positions (I know, I know, normally it is the infantry and certainly not the cavalry… but I’ ll justify myself with the abstract nature of the game!).

The result was very pleasing. Battles often begun with a cavalry skirmish, as the opposing knights vied for control of the plinths located in dominating positions in the centre of the board. Oh, and by the way, that’ s why the blocks are called ‘ plinths’ , as they often ended up becoming the bases of those temporary equestrian statues. Soon, the knight on a plinth became the signature image of the game, perhaps its most characteristic visual element, which instantly sets aside Shuuro from normal chess.

Then it was a case of deciding how to place the plinths on the board. I thought of allowing players to deploy plinths first, and then deploy their armies (more about this later), but that led quite quickly to optimisation and the battlefields ended up looking always the same. Then I thought of offering some pre-made set-ups for the plinths, representing in abstract some famous battlefields of history, but once again the number of options was quite limited (even though I find the idea still quite appealing, maybe as set ‘ scenarios’ – who knows?). Then, once again, I thought of a system I had seen used in wargaming – the setting of terrain elements by dividing the table in sectors and then rolling on a chart to see what terrain is present in each sector. So at first I thought to play on a 10×10 board, using a ten-sided die to place the plinths, but this was a bit too random, occasionally creating battlefields that were a bit too one-sided. Finally, partially inspired by the square shape of the plinths, and partially still wanting to play on a larger board, I decided for a 12×12 board, divided into four 6×6 quarters. This would allow me to use a normal six-sided dice to place the plinths (the humble D6 coming always recommended by the priestly wisdom of my favourite games designer). The division in four quarters would make sure that, even though the plinths are placed at random, their distribution is more homogeneous across the board (two per quarter), maintaining a better balance between the two opponents.

Then, the armies…

So, with the dice ensuring that every game of Shuuro is going to be different, the board was set. It was time to go back to the armies and set in stone their values. I wanted the pawn to still be the unit used to measure all of the other pieces, so it made sense to keep its value at 1. The value of the long pieces was increased in proportion with the amount of squares they can control in a 12×12 board in comparison with a normal 8×8, and the length of their move. This was done with an equation that tried to take into consideration both the number of squares they can control on a larger board and the maximum move they can make. It was then a case of playtesting and adjusting these abstract ‘ calculated’ values with battlefield experience and, let’ s admit it, a good dose of very unscientific gut instinct.

That’ s how I came to the current values of the pieces, which were initially 1, 4, 4, 7 and 11, but I then multiplied them by ten for two reasons. The first is that both the playtesters and I agreed that mysteriously it felt easier to add in tens than in units when working out the total value of the army (if you can explain this, I’ d be happy to hear). The second is that with tens it would have been easier to decide that a piece was worth something less than a full value, for example, the knight was worth 35 rather than 40 before it gained the ability to jump onto the plinth… Eventually I didn’t need this second reason (but I might in future expansions), but the first stood firm.

The last part of this process was to limit the amount of pieces of a certain type that the players were allowed to buy with their points. This was born out of wanting to limit the most extreme armies that could exploit any weakness in the relative value of the pieces, and keep the forces a bit more varied and balanced. I kept these limits proportionally decreasing with the increase of the points cost of the piece, to ensure players could spend more or less the same amount of points in each type of piece (except for the pawns… too cheap!). So, for example expensive queens were limited to only three per army, while you can have up to eighteen inexpensive pawns. I Finally rounded them all up in multiples of 3, to maintain the mathematical relationship with the 12 squares, the six faces of the plinths and of the dice… for purely aesthetic reasons, really.

Finally, the maximum number of pieces in the army is simply set so that it’ s not possible that the armies reach the fourth row (considering 32 pieces and 4 plinths). This ensures that the two armies are always separate by at least six empty rows. I also choose the pieces to be blue and red rather than the traditional black and white.

This was because of three reasons:

– To once more reinforce Shuuro’ s nature of abstract military simulation, where the two opposing sides are always traditionally ‘ Red’ and ‘ Blue’ .

– To set the looks of Shuuro aside from traditional chess straight away.

– To ensure that neither side had a ‘ always go first’ rule attached to (as White would have had)

Deployment and game-play

With the armies selected and the battlefield randomly set thanks to the dice, it remained to be decided how the players were going to place the pieces on the board. It seemed natural, with so many elements borrowed from wargames, to just go for another one (Shuuro was more and more shaping up to be a chess-wargame). So I decided that the players were going to place their pieces on the board one at a time, alternating. This means that from this point onwards the game was already on, as each piece placed was effectively an attack that the opponent needed to think about. To keep the looks of the armies a bit closer to normal chess, I added a few stipulations: that the King was to go down first and in the middle of the board, that all of the non-pawn pieces went down next, therefore starting behind the pawns, and finally that pawns started from the second row. These rules took care of the wackiest and most extreme deployments, keeping a more chess-like feel to the battlelines.

Gameplay was easy. I wanted to keep the rules as simple as possible, ideally exactly the same as normal chess, to make sure that players could simply play chess in a different environment. In the end I was forced to eliminate the castling move, as it was becoming really complicated to wok out a way to do that in Shuuro, and in the end, castling was effectively done during deployment, when the players could easily ensure that their king already started the game in a ‘ castle’ .

Even more variety

It is worth noting that many of the things we tried during development, and that were then dismissed, have been captured and preserved in the form of game variants that are presented at the end of the rules. This gives you a nice insight in to what the game looked like at several stages during its development. For example, you can still play Shuuro with no limits to the number of pieces you can field, just using the points limit – so you can field that all-queens army!

The one thing that people always ask about, but that at no time was a variable I wanted to consider is the so-called ‘ exotic pieces’ . Adding new pieces to the game of chess seemed something that other have tried, and that I personally did not dare to attempt. What I wanted, my ‘ design aim’, so to speak, was not to change chess. I wanted a game that was simply chess in a different setting. Basically, I wanted the challenge to be about choosing a chess army and fielding it in a different, more rugged, battlefield. But at its core I wanted the game to have maximum accessibility and to respect the game of chess, so I ruled out extra pieces from the start. Perhaps one day an expansion will come… And, speaking of expansions, the natural development of Shuuro for me was that of making it into a four players variant. With the Sanskrit name of Turanga, it will be our next game, and playtesting it has been wild fun. I only tell you that red and blue are now allied against green and yellow (a penny if you can guess what these colours represent…) and that, much like in bridge, the two allies sit opposite each other and cannot communicate after the start of the game… it takes real team work to win at Turanga!

The name of the game

Bizarrely, one of the most difficult parts of this design process was naming the game. The most obvious choice was something like ‘ battle chess’ or ‘ chess war’ , but all of this kind of names were already taken. So for a while I decided for the shamelessly self- celebratory ‘ Cavachess’ . This was obviously like calling it ‘ my chess’ , and it had the added nice joke of sounding like ‘ hippo chess’ in Japanese (I’m often in Japan, because my wife is from this fascinating country).

The name lasted a little while, and even made it into printed material (see the book ‘ Hobby Games 100’ by James Lowder), until an Italian friend pointed out that ‘ Cava-chess’ would sound to Italians something like ‘ Cava-loo’ , because slang Italian for ‘ toilet’ is ‘ cesso’ , pronounced exactly like chess with an ‘ o’ at the end – not an ideal name in my native country!

In the next months, very many names were concocted and rejected, in a huge and time consuming brainstorming operation. Eventually, I decided to go for Sanskrit, mainly because ancient India is the place where chess originated, but also because it’ s a really cool-sounding language and because, as it wasn’ t one of the languages we were going to translate the manual into, it kept things fair. So I did some digging into war-like Sanskrit words and ‘ Shuuro’ , which means ‘ warrior’ , won the selection process.

The outcome

Well, in the end I had a game that I really liked. Why do I like it so much (other than being my brain-child, that is)? Well, it is because every time I play, it feels different, as the armies and the position of the plinths change. It is because I can challenge players that always crush me at chess on more even grounds, their opening theory destroyed by the game’ s variable set up. It is because it only has one page and a half of rules and it takes five minutes to explain to someone who already knows chess. It is because it pushes my buttons both as a chess player and as a wargamer, respecting both games.

Reality hits: how do you make a boardgame?

So the game was designed and tested, now it was a case of turning into a reality. I thought about trying to convince an established games company to make the game, but a part of me really wanted to have my own little business… so I decided to try this new experience, even though I was proceeding veeery slowly under my own steam. Enter the one force that most contributed to turning Shuuro from a prototype into a commercial boardgame: this force is called Alberto Giusti. This old friend of mine (we’ ve been friends and/or schoolmates from primary school to university and beyond) is a ‘ serial entrepreneur’ and saw potential in my idea. With help and advice from my friend Hugo Pritchard, we set up River Horse LLP (and the hippo joke keeps going…), and we embarked upon the challenging process of making the board game. Without Alberto’ s whip on my back, and his help with everything business, and particularly web marketing,

So the game was designed and tested, now it was a case of turning into a reality. I thought about trying to convince an established games company to make the game, but a part of me really wanted to have my own little business… so I decided to try this new experience, even though I was proceeding veeery slowly under my own steam. Enter the one force that most contributed to turning Shuuro from a prototype into a commercial boardgame: this force is called Alberto Giusti. This old friend of mine (we’ ve been friends and/or schoolmates from primary school to university and beyond) is a ‘ serial entrepreneur’ and saw potential in my idea. With help and advice from my friend Hugo Pritchard, we set up River Horse LLP (and the hippo joke keeps going…), and we embarked upon the challenging process of making the board game. Without Alberto’ s whip on my back, and his help with everything business, and particularly web marketing,

Shuuro would have probably taken ten years to see the light, if it actually made it at all. Instead, I willing submitted to the crack of the whip (I knew it was for my own good!), and after about a year of really hard work, we had in our hands a first print run of a great and classy-looking game! Not that I’ m biased…

And of course we couldn’t have made it on our own. This adventure has only been possible with the help of the friends that helped making Shuuro a reality, whose names are in the game credits, and who I wish to once more thank from the deep of my heart.

Intrigued? Snap up a copy of this lovely variation of wargaming today from our webstore!