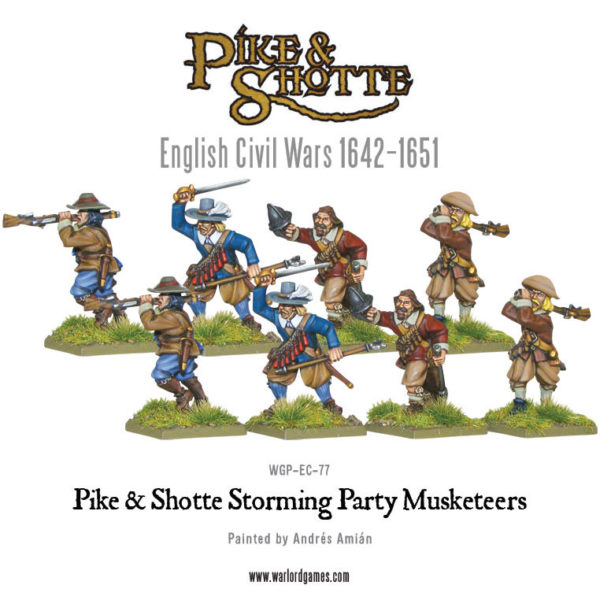

The mainstay of the armies of the era, the roles of the musketeer and firelocks were pivotal in this new age of warfare. The pike blocks of infantry were usually supported on each flank by ranks of handgun armed men. The role of the musketeers was to pour as much firepower at the opposing enemy unit as possible, then the pikes would engage and the firearms infantry would turn their weapon around, and club the enemy to death!

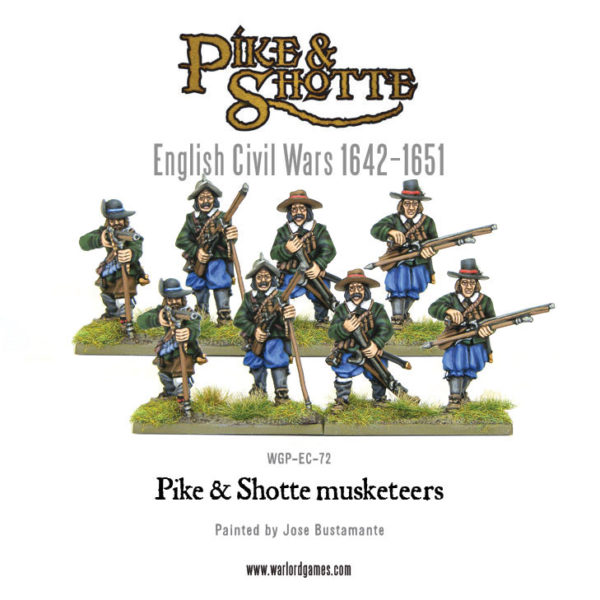

These weapons were far from being accurate, being smoothbore firelocks and matchlocks that were best used to frighten an enemy into submission. Such was the inaccuracy of these weapons that they rarely actually hit their intended targets, despite the huge numbers. The musketeers would be protected by the pikemen whose main role was to fend off any cavalry. The entire unit could form into a hedgehog, with the pikes’ length enabling them to fend off cavalry, whilst the musket armed troops could shoot into their ranks. However there were instances of musket armed troops fending off cavalry on their own.

Another factor in the role of firearms was a tactic of firing in a salvo, where upon the men would be arranged two to three ranks deep, and the handgun equipped infantry would fire en masse at close range, with each wing of musketeers taking turns to fire. This way while one would pour fire into the approaching enemy, the other could be held in reserve. This tactic was seen during the English civil war against the formidable Highland Charge, and the army of Montrose also utilised the salvo to great effect. Due to the complexity of the manoeuvre however it could only be performed by a well-trained and a highly disciplined army.

The matchlock was fired using a lighted length of saltpetre treated rope held in place by the S shaped lever, which when touched to the priming pan would ignite the gun powder.

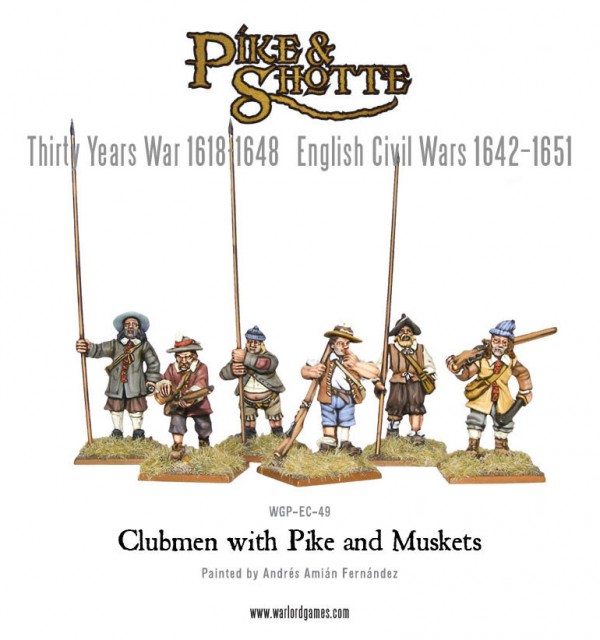

In the 16th century these weapons were known as arquebuses and had started to be used in large numbers. Cheap to make and manufacture, these handguns began the process of replacing the bows and arrows of earlier years with a weapon that would eventually dominate wars thereafter. Despite the new innovation, these earlier handguns lacked the advantage that bows and crossbows had – that they could be used in wet weather, whereas the matchlock obviously could not.

The musket was also introduced in the 16th century, and was so much heavier that they required their own support to be effectively used. Large and cumbersome, these weapons required a lot of kit to use them. Later in the century the barrels were shortened and could then be used without the aid of a musket rest.

By the time the flintlock was introduced, this new technology would come to dominate the battlefield. These were also known as “doglocks” and “firelocks” and were rolled out not just to the infantry but to cavalry also. The firing mechanism of this new weapon was a vast improvement of the earlier wheel lock and matchlocks.

Previously armies would have had to carry a horde of match cord with them on campaign. This new evolution in firearms freed up the logistics of transport. The weapon was more expensive to make but was far more useful on the battlefield.

Another key introduction to the musketeer’s arsenal would be the bayonet. Starting as humble knife jammed into the end of the weapon, this simple innovation meant that the weapon was turned into a shortened pike, rendering the need for pikemen redundant.