Frank Jastrzembski, M.A. introduces us to the colourful and fanatic Armies of the Mahdi (1881-1898)

These black chaps know how to fight and how to die. –British soldier speaking of the Ansars.

September 2, 1898. Along a five mile desert front, 40,000-60,000 fanatic followers of the Mahdi, or Ansars, descended upon a collection of British, Sudanese, and Egyptian soldiers with their backs pinned up against the Nile River. Roaring war chants were supplemented by the repetitive recital of “There is but one God and Muhammad is the Messenger of God” as thousands surged forward. Amirs, the equivalent of battalion or regiment commanders, motivated their men with Islamic chants and through the display of their own personal bravery.

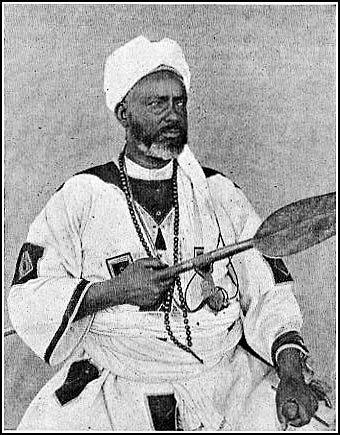

Some Amirs sported chainmail and carried swords captured during the Crusades 600 years beforehand. Thousands of flags with elaborately embroidered inscriptions rippled as a gust of wind encompassed the battlefield. A wide array of brightly colored patches decorated the soiled white tunics of the Ansar soldiers. One British soldier present was awestruck by the spectacle put on by the medieval-styled army and commented, “It was a sight to be remembered as long as ever life lasts – a pageant that I imagine can never recur.”

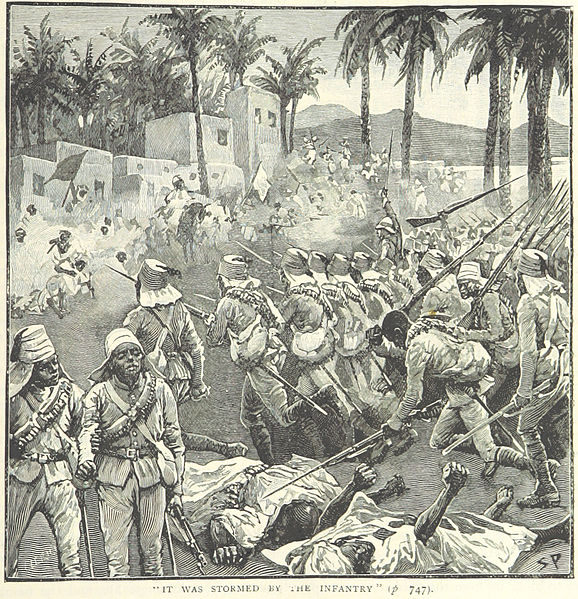

The defending army under the command of General Herbert Kitchener, less than half that number, impatiently waited until the black tide descended upon them. The defenders had the distinct advantage of being armed with modern firearms and artillery, and were under the protection of nearby gunboats. As the attack began to pick up momentum, the Ansars came under a shower of bullets and shells that tore their ranks to shreds and left gaping holes in their formations. Deprived of the element of surprise, the attack never stood a chance despite the overwhelming advantage in numbers. Nearly 10,000 were killed and the same number wounded as thousands of lifeless bodies were left strewn over the battlefield. One English journalist soberly observed that the attack “was not a battle but an execution.”

Those who witnessed the slaughter were enamored by the bravery displayed on that day. “The valour of those poor half-starved dervishes [Ansars] in their patched jibbahs would have graced Thermopylae,” an impressed British soldier proclaimed. Despite the validated show of bravery, the Mahdi’s once proud army was forever shattered on the fields of Omdurman.

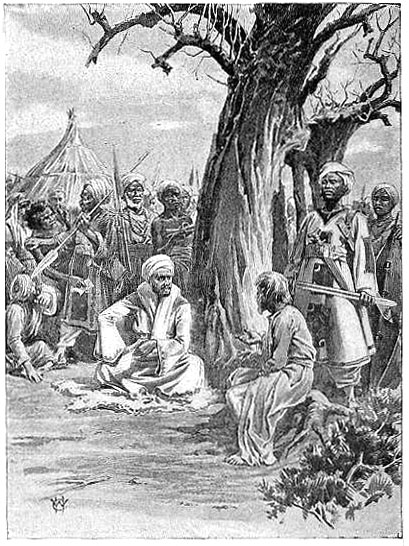

Seventeen years before Omdurman on June 29, 1881, a humble Sudanese religious man by the name of Muhammad Ahmad made a significant proclamation. He announced to the underprivileged of Sudan that he was the new messiah, or Mahdi. He declared a new holy war and called to peasants from all of Sudan to rise up and overthrown the oppressive Egyptian rule. His followers became known as the Ansars, or “Helpers,” and grew from a dozen to many thousands in a short period of time. The Ansars, or Dervishes to the British, developed a reputation as tough and fanatical fighters, which they demonstrated in a number of victories they delivered upon the Egyptians.

In 1883, an arrogant ex-British officer, Bill Hicks, set out with 10,000 Egyptian soldiers to defeat the Mahdi’s growing army. Near Kashgil in November, his army was ambushed and the 10,000-man force was annihilated. The decapitated head of Bill Hicks was proudly presented to the Mahdi in Omdurman.

A second expedition under another British officer, Valentine Baker, led an ill-fated column of 3,700 out into the desert. Baker was accompanied by the maverick Colonel Frederick Burnaby (Warlord Games produced a stunning miniature of Burnaby) arrived just in time to take part in the expedition. Baker’s Egyptian soldiers were armed with modern rifles, accompanied by four Krupp guns, two Gatling guns, against a foe armed with spears, shields, and an assortment of firearms.

The Mahdi’s followers surprised and boldly struck Baker’s column in February of 1884, near El Teb. Their frenzied attack easily sliced through Baker’s densely packed square formations. Egyptian soldiers tried to hide behind each other, and others begged for mercy, only to be unsympathetically speared in the back and to have their throats cut. It was all over in eight short minutes. Out of the 3,500 men of the Egyptian column, 2,225 soldiers and 96 officers were killed.

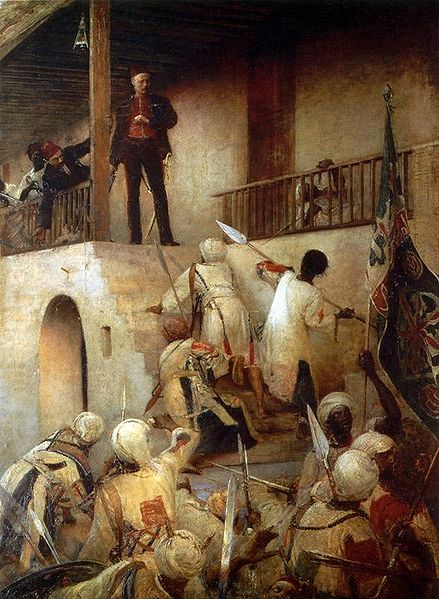

The apex of the Mahdi’s success came when he captured the city of Khartoum in January of 1885. After a ten-month siege, his men broke into the city, and butchered the entire Egyptian garrison, including the renowned British General Charles George “Chinese” Gordon. Ironically, the Mahdi died only six months later of typhus at the age of forty. Khalifa Abdullahi succeeded him, but from the moment of the Mahdi’s death his armies would never see the same successes as in the early years of the Mahdiyya.

Outfits

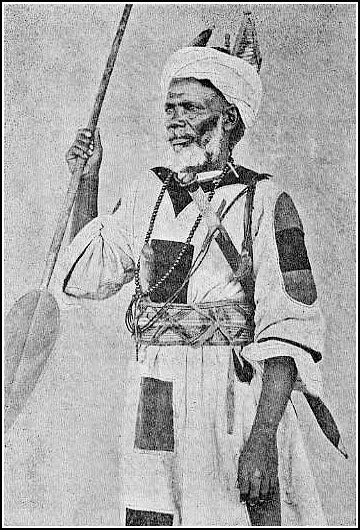

The typical Ansar uniform was inspired from the clothing of a poor Sudanese peasant. The Mahdi proclaimed the official outfit of his followers to be a loose cotton white tunic called a jibbeh, which hung down to the knees and below the elbows, close fitting cotton trousers, sandals, a skull-cap or white turban, and a girdle of straw worn around the waist. The Egyptian fez was strictly forbidden.

The jibbeh was only widespread in the main army during the early years of the Mahdiyya (1883-1885). Most early battles were fought by levies, not the core of Mahdi’s army. The levies typically donned a cotton waist cloth, cotton trousers, or a cotton robe. Their clothing was rarely a crisp white after extended campaigning in the African desert.

The jibbeh was covered in colored rectangular and square patches originally used to repair tears or holes. These decorations developed into a mark to demonstrate allegiance to the Mahdi. In the years leading up to 1885, a patch or two of red and dark blue were commonly sewn on the garment. Later colors adopted were black, dark blue, medium blue, turquoise, red, and green.

The hair of an Ansar soldier in the early years of the Mahdiyya was worn to intimidate his enemy. It was usually frizzed and stiffened so it stood six to eight inches from each side of the head. In later campaigns, heads were shaved and Ansar soldiers donned red and dark blue patches on their skull-caps. The Beja tribesmen were the exception, and normally did not shave their heads.

Flags

Flags played a critical in the organization of the Mahdi’s armies. In the early days of the Mahdiyya, the Mahdi conferred “flags” or rayya to those who supported his call to wage a holy war. A flag came to signify a body of troops under a specific commander. Within his main armies, each Amir had his own unique flag to be identified. When his army became more organized, the Mahdi divided his forces into flags, each under his three Khalifas identified by color (Black, Red, and Green). The Mahdi’s own flag was green, a direct associated with the Prophet Muhammad. Ansar flags carried Arabic inscriptions and slogans that proclaimed the Mahdi to be the true successor to Muhammad, and also included other Muslim creeds, names of saints, or even names of local commanders.

Armaments

Almost all warriors were armed with melee weapons. They ranged from short daggers, hooked knives, ten-foot long spears, short throwing spears, and lastly double-edged cross hilted swords. One British solider recorded that what the Ansars lacked in firepower they “assuredly made up in bravery.”

Though minimal, the Ansars were not without firearms. Their armory included captured Egyptian Remington Rolling Block breech-loading rifles, outdated muzzle-loading rifles, and British Martini-Henrys. Also in their possession in a small quantity were modern Krupp guns, brass mountain guns, and machine guns captured from the Egyptians. Some of the Ansars carried shields, which were made from rhinoceros, crocodile, or elephant hide, and said to be capable of deflecting a bullet.

Tactics

The only vital strategy when facing a western armed and trained army, Egyptian or British, was the elements of surprise and shock. Ansar armies would launch furious assaults from multiple directions or attempt to encircle their enemy. The key to success relied on the warrior’s ability to speedily rush the defenders or inch close enough to their lines under the protection of cover. Attacks were usually launched in wedge-shaped formations. Mounted Amirs would inspire their men with Islamic prayers and slogans but provided easy targets for British or Egyptian riflemen.

Wargaming the Mahdi’s Army

Are you interested in building the fierce army of the Mahdi? Don’t be turned away by their lack of firepower. With the right element of surprise and usage of cover, your enemy will be easily overwhelmed in a furious assault! The colorful patchwork on the Ansar outfit, the brilliantly embroidered flags, and fearsome array of melee weapons, will leave others gamer envious of your beautifully detailed and exotically painted army.

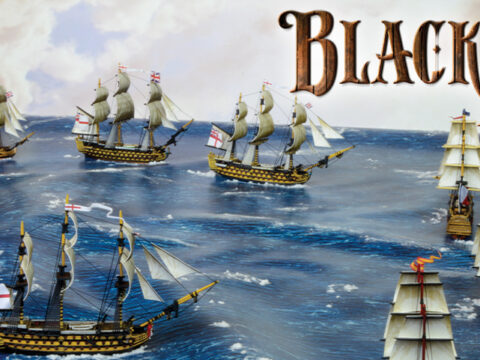

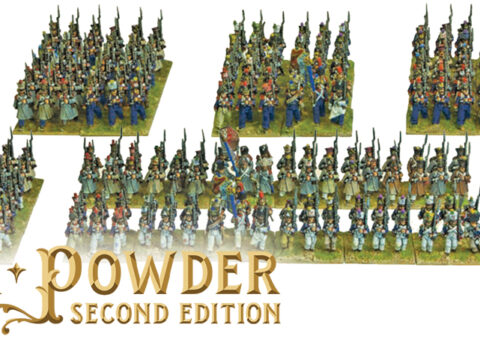

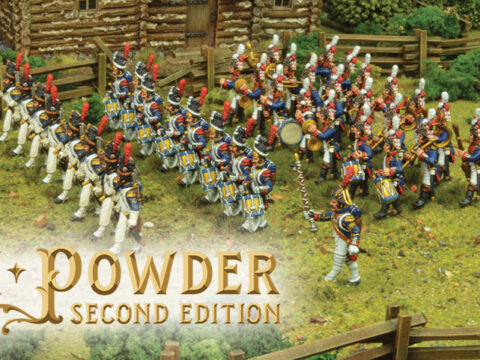

Warlord Games offers a line of miniatures ideal for mustering the might of the Mahdi. A plastic boxed set of forty ferocious Ansars (circa. 1881-1884), produced by Perry Miniatures, can be purchased on the online store. The miniatures can certainly be used for waging war in any period of the Mahdiyya, beginning with the initial rebellion in 1881, and concluding with their ultimate defeat at Omdurman in 1898. Warlord Games also offers a rich ruleset for this era (Blood on the Nile), which is a supplement for the Black Powder game rules.

Further Reading

- Featherstone, Donald. Omdurman 1898: Kitchener’s Victory in the Sudan. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1994.

- Johnson, Doug and Greg Rose. “A Note on Mahdist Flags.” Soldiers of the Queen 14 (August 1978): 7-15.

- Johnson, Doug and Greg Rose. “Organizations And Uniforms Of The Mahdist Armies, 1883-1898.”

- Kiley, Kevin F., Digby Smith, and Jeremy Black. An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Military Uniforms of the 19th Century: An Expert Guide to the Crimean War, American Civil War, Boer War, Wars of German and Italian Unification and Colonial Wars. London: Anness Publishing, 2010.

- Ziegler, Philip. Omdurman. London: Collins, 1973.

Frank has a passion for researching and writing about forgotten wars and soldiers of the 19th century. Having graduated from John Carroll University with a BA in History and from Cleveland State University with a MA in History, now travels the world whenever the chance presents itself, managing to find the nearest well known or obscure battlefields to visit.

As an avid tabletop and miniature wargamer, battles are fought against his brother and a close group of friends who share the same passion for waging these little wars. If you’d like to find out more from Frank pop over to www.frankjastrzembski.com and check out the forthcoming release of his book dedicated to the Spartan stand of Valentine Baker at Tashkessen in 1877

Do you have an article within you? Are you itching to show your collection to the world of Bolt Action? Then drop us a line with a couple of pictures to info@warlordgames.com