Opening Moves

Napoleon wanted the battle to start at 9am, but that was a pipe dream. The ground was sodden and his troops, especially the cannon, were struggling to get into position. The fields and farm tracks were in a poor state due to the rain-sodden conditions and the battle’s start time had to be delayed. Wellington badly needed this extra time, which would allow the Prussians to march to his position.

Diversionary Attack

The French cannons roared at 11.20pm and ten minutes later Jerome Bonaparte’s Division, Reille’s strongest, moved forward to attack Hougoumont. The Nassau and Hanoverian light infantry defending the chateau’s wood were quickly dislodged by men of Bauduin’s Brigade, but when the French skirmish screen reached Hougoumont’s orchard they were faced by a tougher proposition altogether, as the Coldstream Guards put a halt to the French advance. Bauduin began forming a heavy brigade column under cover of the woods, but this was broken up by British howitzer fire, which also killed the brigade commander.

This diversionary attack escalated during the day, Reille sending forward battalion after battalion, turning the diversionary attack into a full scale battle in itself. The fight for the buildings of Hougoumont was to tie up manpower that would be much needed later on; Napoleon’s hope that the attack would draw off Wellington’s reserves worked in reverse, the French eventually committing three brigades.

Prussian Reinforcements En Route

At around 1pm, an aide-de-camp from Marshal Ney brought news that the attack of D’Erlon’s Corps was ready to get under way. Shortly afterwards, the Emperor became aware of the first Prussian columns marching to Wellington’s aid. It was first thought that this movement near the village of Chapelle St. Robert was Grouchy’s cavalry, but a captured warrant officer of the 2nd Silesian Hussars soon dashed Napoleon’s hopes. He carried a letter from Gneisenau to Muffling, making it clear that Bülow’s Corps was to attack the French right wing.

Napoleon sent an aide with new orders galloping off to find the missing Grouchy. The order, although confusing, had at its core a need for him to march to his Emperor. Grouchy, although urged by Lieutenant General Count Gerard “to march to the sound of the guns”, would not receive those new orders until it was too late. He had chosen to stick to the orders he had, which were to pursue the Prussians towards Wavre. In the meantime Napoleon ordered Lobau’s VI Corps to take up a flank position against a possible Prussian attack from the east.

The Grand Battery

Eighty guns had been moved to a low ridge forward of the main French position, and shortly after 1pm the preparatory bombardment by the Grand Battery began. This barrage would have a limited effect on Wellington’s army, his forces being drawn up on the reverse slope and the rain-softened ground prevented the cannon balls from bouncing far. As the battery targeted the whole of the Allied front, there was also a limited concentration of firepower. But besides killing soldiers, Napoleon hoped that the sight and sound of the Grand Battery’s fire would have a devastating effect on the morale of Wellington’s men.

Thirty minutes later the 33 battalions of D’Erlon’s Corps, the divisions of Quiot, Donzelot, Marcognet and Durutte stepped forward to attack. They had over 1,000 metres to cover across open, sodden terrain. As the leading battalions reached the Grand Battery the guns fell silent to allow the infantrymen to pass through the position, a ‘passage of lines’. Once through the guns the battalions formed in battle formation. Voltigeurs were sent forward to cover the assault whilst the remaining battalions, rather than forming battalion columns, formed battalion lines. Battalions in Donzelot and Marcognet’s Divisions had their battalions closely spaced behind one and another, while Quiot and Durutte adopted the same formation but at brigade level. These were strange formations for the French to employ, but they were the result of a conscious decision made by D’Erlon. He was a Peninsular veteran who, having seen the attack column fail so many times against the British, went for a compromise. He had created the weight and visual effect that column tactics brought, yet the line frontage brought extra firepower.

Advance

It was close to 2pm when everything was ready, as 16,000 Frenchmen rent the air with shouts of “Vive l’Empereur!” and loud cheering, “En avant!” As they descended into the shallow valley between the French and Allied lines the French cannons roared again.

As the French came on, the Allied artillery went to work. The formations adopted by the attacking French could hardly be missed and cannon balls and canister took a terrible toll on the French, but they still maintained their advance. Charlet’s Brigade of Quiot’s Division moved against La Haye Sainte, quickly isolating the farmhouse and its German defenders with the help of a number of squadrons of Cuirassiers. The Prince of Orange saw the danger and ordered the Hanoverian Luneberg Battalion forward to reinforce the farm. The Hanoverians duly advanced in line formation, but failed to notice the 1st Cuirassier Regiment. The French heavy cavalry charged and the Hanoverian battalion was destroyed in the blink of an eye. The cuirassiers continued forward to the crest, thus forcing Ompteda’s KGL and Kielmensegge’s Hanoverian Brigades into defensive squares.

Donzelot’s and Margognet’s attack formations were now nearing the crest of the ridge, supported by Pegot’s Brigade from Durutte’s Division, whilst Durutte’s second brigade under Brue moved against Papelotte. The main attack would fall upon Wellington’s left wing, an area commanded by Sir Thomas Picton. The first line consisted of van Bylandt’s 1st Dutch Belgian Brigade, whilst the second line was made up of Picton’s 5th Division. Both formations were in dead ground to protect themselves from the cannonade.

The French attackers had suffered terribly from artillery fire and now they were being peppered by musketry from Allied skirmishers. Although there was some wavering, they still marched on. As the French reached the crest Byylandt’s skirmishers withdrew to their parent battalions. As they moved through the British skirmishers they were loudly booed by their allies who thought they were fleeing in the face of the enemy. The Dutch and Belgian battalions now rose to meet the oncoming French. Van Bylandt’s Brigade had been mauled two days before at Quatre Bras and they had been rattled by the fury of the cannonade that had played on them for nearly an hour; they soon retired in disorder, leaving a gaping hole in Wellington’s line.

It was time for Picton’s Division to stem the tide. Picton himself brought forward Kempt’s Brigade and was shot in the head, dying instantly. Kempt’s Brigade lined the ragged hedge that bounded the sunken lane and poured a series of volleys into the advancing French. While many fell, the advance continued and by sheer weight of numbers Wellington’s line was beginning to creak.

The battle was in the balance.

Find out more in Part 3:

History: The Battle of Waterloo – part 3

Back to History: The Battle of Waterloo – part 1

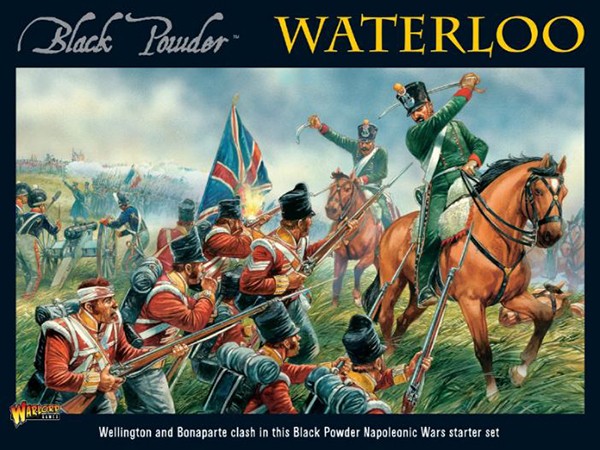

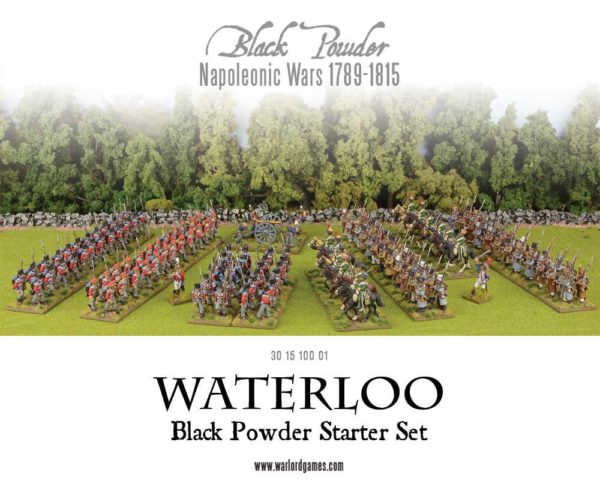

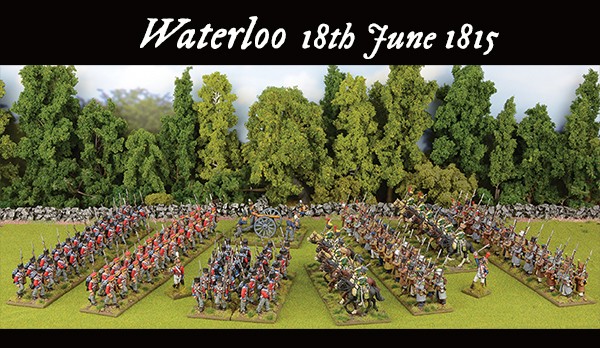

Begin your Waterloo!