We’ve arrived at the climax of the Napoleonic Wars. Returning from exile, Napoleon rallied his forces and began the campaign that would end at Waterloo.

Following his defeat at the Battle of Leipzig and eventual loss of the War of the Sixth Coalition, Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba. Kept under guard, he watched the squabbling Congress of Vienna from afar.

Deeply unhappy with the treatment of his beloved France by the Congress, and alarmed at British and Austrian calls to exile him to the windswept island of St Helena, Napoleon slipped his leash aboard a French brig with just under a thousand men, returning to France after just nine months in exile.

During his exile, many French prisoners of war had been returned to their homeland from camps across Europe. These battle-hardened veterans flocked to Napoleon’s banner, and his army rapidly swelled, unchecked by the few Royalists who remained loyal to the Bourbon regime.

in March 1815, Napoleon entered Paris at the head of his army, accompanied by several of his trusted Marshals. He hoped that his meteoric rise to power would bring the great powers of Europe to the negotiation table, too war-weary to risk fighting yet another costly campaign against a proven French army.

Unfortunately, it was not to be, and the newly-formed Seventh Coalition declared Napoleon an outlaw on 13th March, followed swiftly by a declaration of war.

With his enemies amassing all around, Napoleon decided to launch a pre-emptive strike against a Prussian and a British army assembling in Belgium. On 15th June, his army rampaged across the Belgian border, sweeping aside the Prussian pickets at Charleroi.

From this position, Napoleon commanded the ground between the British to the west and the Prussians to the east. If he could stop the armies merging, he could destroy them one-by-one, eliminating the major threat to his new regime.

Ligny

Expecting a characteristic flank attack, the Coalition forces were covering the good roads towards Mons. Having identified the weakness between the British and Prussian armies, Napoleon divided his force into three groups, with the left wing under Marshal Ney advancing towards the crossroads at Quatre Bras, while Napoleon and Marshal Grouchy took the fight to the Prussians at Ligny.

Blucher’s corps was arrayed along the road to the east of Quatre Bras, standing ready to repulse the right and centre wings of Napoleon’s advancing army. From the beginning, Blucher was counting on Wellington to cut through the opposition at Quatre Bras and take the attacking French in the flank, ultimately pinning and destroying Napoleon’s army.

Undermined by poor positioning that left his units exposed to French artillery on the heights and a lack of reserves to resist counter-attacks, Blucher was driven from Ligny but managed to salvage the majority of his force and remain in the vicinity to decisively support the action at Waterloo on the following day.

Ligny is a fantastic example of a tactical victory that contributed to a strategic loss. While Napoleon had defeated the Prussians and gained the ground between the two armies, he had been unable to destroy or rout the Prussian army, which still remained as a formidable fighting force.

Quatre Bras

Blindsided by false reports of a flank attack, the Duke of Wellington was forced to leave a high society ball as the French left wing closed on the gap between the British and Prussian forces.

Concurrent to the action just up the road at Ligny, the struggle between the left wing of the French army under Marshal Ney and an Anglo-Dutch army under the Prince of Orange and the Duke of Wellington was a key part of Napoleon’s strategy to force the two armies apart.

With the bulk of the Coalition army either engaged at Ligny or on the march, they were left with a single division facing down three French infantry divisions and a cavalry brigade.

The action began at 2pm, while the Prussians were being savaged at Ligny. Under the cover of a massed artillery barrage, columns of French infantry pushed back the defending Dutch infantry to the crossroads.

With the arrival of British reinforcements, the Coalition forces were able to repulse repeated French attacks. The heroism of individual British regiments like the Black Watch and 28th Foot ultimately turned the tide of the battle and prevented the French from gaining the crossroads.

Waterloo

Despite the British success at Quatre Bras, the Prussians had been driven from the field at Ligny and the Coalition army was forced to retreat northward. Preventing Marshal Ney gaining the crossroads at Quatre Bras slowed the French pursuit and gave the Duke of Wellington time to choose his ground.

Two days later, both armies would clash again at Waterloo!

As both armies had retreated in good order, Wellington was able to organize one of his characteristic defensive battles, arrayed along the high ground, standing between Napoleon’s army and Brussels. From this position, the British army withstood numerous assaults on their positions, including several charges by the elite French heavy cavalry and a massed last-ditch assault by the Imperial Guard.

The Prussian army began to arrive on the French flank in the afternoon, turning the tide against Napoleon. With their armies combined, the British and Prussian forces were able to drive the French from the field and secure a victory.

Napoleon’s loss at Waterloo marked the end of the First French Empire and the Napoleonic Wars as a whole. He would end his days in exile on the South Atlantic island of St Helena.

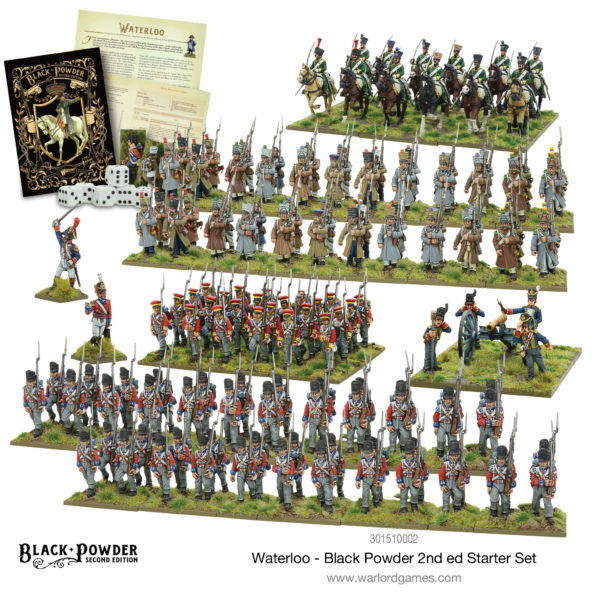

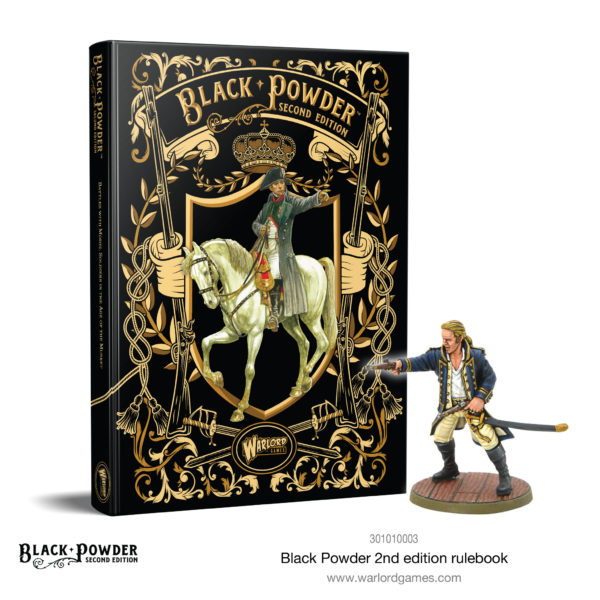

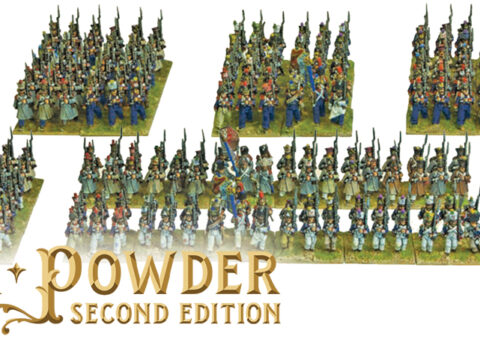

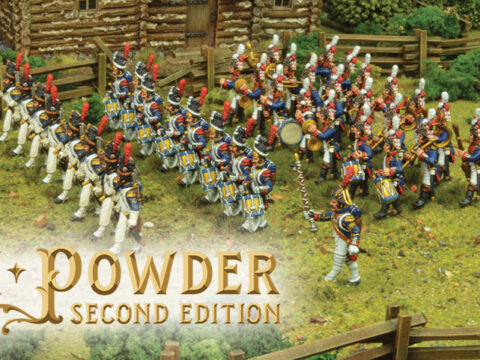

The 100 Days in Black Powder 2

As the climax of the Napoleonic Wars, this iconic campaign is the perfect starting point for anyone looking to get into Black Powder. Grabbing our excellent Waterloo starter set, which we’ve updated for the release of the second edition will give you plenty of models to represent sections of Waterloo or the earlier battle of Quatre Bras.