This article from David Friemann examines the 92nd Infantry Division, more commonly known by the moniker The Buffalo Soldiers. It also presents some rules for using some legends of the division in your games of Bolt Action.

We must be the great arsenal of democracy.

– Franklin Delano Roosevelt, December 29th, 1940

When the president of the United States said these words in one his immensely popular “fireside chats”, he aimed to explain to Americans his administration’s decision to support Great Britain in its desperate confrontation with Nazi Germany. The United States were to supply an ever-growing amount of war material to its European ally, without directly entering the war, a prospect dreaded by the majority of the population and highly unpopular with most of the country’s politicians. This general tack would remain the official policy of the United States for little less than a year, when the country entered the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Apart from sending out the fleets, army and air forces, another mobilization at home turned the United States’ industry, still reeling after the Great Depression of the 1930s, into the behemoth that would help turn the tide of the war in Europe and the Pacific in favour of the Allies and end the suffering of countries under the boot of Germany, Japan, Italy, and their allies.

However awe-inspiring the transformation and output of the wartime industry, and however noble the motives of every infantryman, fighter pilot, and seaman it equipped, the United States were still a country struggling to ensure equality within its own borders. In the southern states of the US, almost every aspect of life, from drinking fountains to busses, and sometimes even graveyards, was segregated between “white” and “colored”. While legally equal, black Americans also experienced racism and marginalization in the northern states.

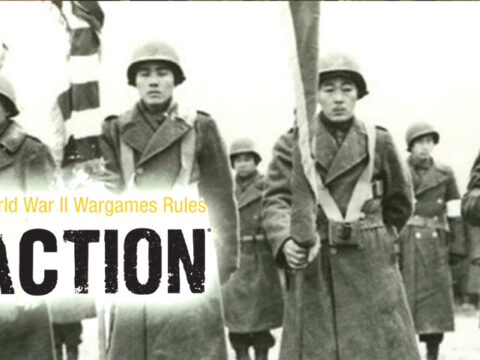

The military was no exception to this widespread inequality. Even though African Americans had served to some extent in all of America’s wars since 1776, the armed forces were still segregated by race when Roosevelt made his famous announcement. Black Americans could, of course, join the military, but their duties were severely limited to support roles, such as truck drivers, cooks, or orderlies. Important as these jobs may be for an army to function, combat duty seemed almost unachievable even for the most eager volunteers from Black communities. With the direct American involvement in the Second World War, the need to provide enough soldiers to fight the Axis powers in Europe and the Pacific at the same time and increasing pressure from civil rights groups in the United States forced the authorities to compromise: Black soldiers would be put into combat but would remain in segregated units.

One such unit was the 92nd Infantry Division, reactivated (after its service in the First World War) on October 15th, 1942. Their historic predecessor units had adopted an old moniker, said to derive from an honorific bestowed upon black soldiers by Native Americans in the 19th century: The Buffalo Soldiers. They would go on to serve in the Italian theatre of war and stay true to their unit’s motto “Deeds, not Words.”

The Buffalo Soldiers

The 13,000 men of the 92nd were volunteers and draftees, led by black junior officers. Higher ranks, however, were filled by white officers, most of them from the South, in compliance with the idea of the National War College at the time that they would know best how to deal with African American soldiers, epitomized by their commanding officer Major General Edward M. Almond, who was given command of the unit by his brother-in-law, Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. He was disliked by the soldiers under him, who felt he “wasn’t on our side, […] didn’t care about black people, at all, none of them.” Almond himself was overtly dismissive of black troops, stating that “[t]he negro officer fails to meet minimum infantry combat standards. He lacks pride, aggressiveness, a sense of responsibility […] his race consciousness seriously affects his general efficiency.” Race relations within the outfit would remain problematic at the best of times, with white replacement officers rising more quickly through the ranks than their African American counterparts to avoid situations where a black officer would command a white subordinate.

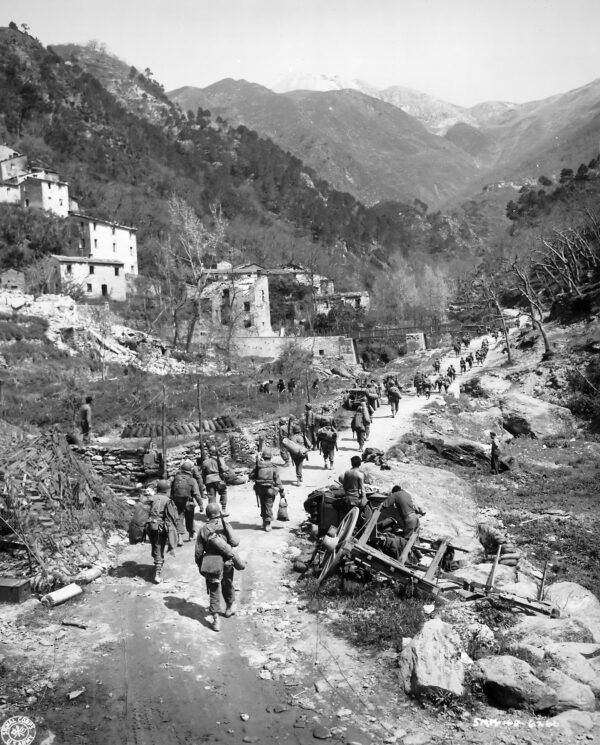

Upon its activation, none of the states would allow an entire black division trained under arms on its territory. Consequently, sub-units of the division were set up in four different locations across the country for basic training, then moved to Fort Huachuca, in a remote part of Arizona, to prepare for combat. After almost two years in the desert, the first unit of the 92nd Infantry Division, the 370th Infantry Regiment, shipped out in July 1944 and arrived on the Italian front near Naples on August 1st. They were attached to the 1st Armored Division and entered combat three weeks later, as part of the US Fifth Army led by Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark. At this point, the Allied war effort in Western Europe had shifted to expanding its hold on Northern France, and with fierce fighting in Normandy troops were needed elsewhere. Out of a total fighting strength of 250,000 men, 100,000 soldiers of the American Fifth Army were moved from Italy to bolster the offensive in France. The troops of the 92nd Infantry Division found themselves in the middle of their high commands’ conundrum of having too few infantrymen to support its many tanks. They were facing off against German and Italian units under Feldmarschall Albert Kesselring, who was fighting a delaying campaign to buy time for the construction of defensive lines in the rough Italian terrain.

Italian Campaign

Together with the colorful assortment of international troops from Britain, the French Colonies, New Zealand, India, Poland, and Brazil stationed in Italy, the 370th Infantry Regiment, first saw action in the Serchio Valley and on the coast of the Ligurian Sea, as the westernmost flank unit of the Allied push northwards. In October, the regiment, whose support units had arrived the month before, was ordered to capture the town of Massa, which planners considered vital because of how close it was to the German naval base in the coastal city of La Spezia. Kesselring’s soldiers fought bitterly and, as in most other sectors of the frontline, held on to their fortified positions. The men of the 92nd Infantry Division were forced to break off the attack after almost a week of combat. They regrouped and began sending out reinforced patrols of up to 80 men supported by machine guns and mortars. The remainder of the division, 365th and 371st Infantry Regiments, arrived in Italy, and was bolstered by the 366th, another all-black unit trained for combat duty but so far relegated to guarding airfields. Replenished, they continued to harass German and Italian forces in the Serchio valley. By then, the late fall snow had begun to fall, and the supply situation, hampered by the terrain and the proximity to enemy strongholds, deteriorated even further. The men of the division relied on pack mules to bring in food, ammunition and materiel.

The American II Corps planned to attack the regional capital of Bologna in early December of 1944 but delayed the offensive until Christmas. By that time, the soldiers of the 92nd Infantry Division had advanced and captured the villages of Bargo and Gallicano, readying themselves for the next push against the axis. But the Germans and their allies struck first. On the morning after Christmas, they began a counterattack codenamed Operation Wintergewitter (Winter Storm) that quickly broke through American lines, surrounding elements of the 366th Regiment. One of its artillery observers, 29-year-old 1st Lieutenant John Fox from Ohio, called down an artillery strike on his own position after it had been surrounded by Wehrmacht troops. Fox was killed in the barrage, along with a hundred German soldiers, and posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. It would take 53 years before President Bill Clinton awarded him the Medal of Honor for willingly sacrificing his own life and allowing his comrades to escape encirclement and regroup with Indian forces further south, where they helped stem the tide of the German onslaught. The next week was spent regaining the ground lost during the surprise attack, and by New Year’s Day 1945, the Allies had largely returned to their position of December 25th.

Planners at Corps headquarters envisioned a large-scale offensive for April, but General Almond of the 92nd Division devised a smaller attack aimed again at the town of Massa, which would put American guns in range of La Spezia. On February 5th, all regiments of the division began moving forward. A diversionary attack would be made by the 365th near the German supply center at Castelnuovo di Garfagnana in support of the main thrust along the coast. General Almond planned to take high ground near Massa and then enter the town itself. The 365th occupied the village of Lama and a nearby hill, and for three days fended off several counterattacks, before being driven back on February 8th. By nightfall of February 10th, it had retaken Lama, but not the important heights surrounding it. Meanwhile, the 370th and 371st, supported by an all-black armored unit, the 758th Tank Battalion, moved along coastal ridges and roads, all heavily mined. The 366th Regiment proceeded on the coastline, battered by German small arms fire, tanks, field artillery and heavy guns at La Spezia. All three regiments had orders to cross the Cinquale Canal at the foot of the hills above Massa. Twenty-two of their tanks fell victim to mines and enemy fire or sunk into underwater craters created by heavy artillery shells. Poor weather conditions made air support impossible, and the Germans kept up continuous fire on the men as they crossed the canal. The shelling and fire from pre-fixed machine gun emplacements prevented engineers from constructing a bridge, so that supplies had to be carried through shallows by hand. Casualties on the canal kept rising, and on February 10th, General Almond ordered a withdrawal, after more than 1,100 soldiers had been killed or wounded.

After this disastrous failure, the Army went about reorganizing the division in preparation of the offensive still planned for the spring of 1945. La Spezia was to remain division’s prime target, but the fighting of the previous months, and especially the attempted attack on Massa in February, had worn down its units. Combat-ready African American troops were not available in sufficient numbers, and the division was brought back to strength by other means. The 365th, 366th, and 371st Regiments were taken off the line and given guard and defensive tasks. From that point on, most of the combat duty would be shouldered by soldiers of the 370th regiment, who had been the first to arrive in Italy in September 1944. Their losses were replaced by another extraordinary outfit of the American army in the Second World War – the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, comprised of second-generation Japanese Americans, or Nisei, who would go on to become the most-decorated unit in American military history. More reinforcements came in the form of the 473rd Infantry Regiment, a unit comprised of white Americans, who had served as anti-aircraft troops but were no longer needed in that capacity due to Allied air supremacy.

The "Rainbow Division"

This refitted 92nd quickly became known as the “Rainbow Division” and found itself on the western flank of the offensive in April 1945. Side by side, Buffalo Soldiers and Nisei advanced once more through the hilly countryside toward Massa, avoiding the roads pre-sighted by German guns. On April 5th, they reached Castello Aghinolfi, a 9th-century castle recently turned into one of the most formidable positions in the German defensive line with bunkers, strongpoints and gun emplacements. 2nd Lieutenant Vernon Baker from Iowa led a handful of his men in a charge against three enemy machine guns and an observation post, taking out their occupants. He then set up his own heavy weapons detachment in an exposed position, drawing enemy fire and covering the evacuation of American wounded. On the night of the same day, he led a battalion through minefields and heavy fire and helped secure the division’s objective. As 1st Lieutenant Fox, he initially received the Distinguished Service Cross, and only was awarded the Medal of Honor 53 years later at the same ceremony, the only living recipient, at age 78. During the following days, the 370th held on to the area surrounding the castle and supported the advancing 442nd Combat Team, who moved up next to it, destroying German resistance nests and bunkers. When more troops were needed to push on, the 473rd came up to protect the left flank against German counterattacks. On April 9th, American tanks first rolled into the outskirts of Massa, but were halted by fierce resistance. The Nisei outflanked the defenders on the Eastern side, finally forcing the Germans to concede defeat and abandon the town the next day. The Nazi lines were thinning, and despite moving their reserve into position around Massa, they could not prevent Allied guns and tank destroyers coming into range of La Spezia. Americans and British shelled the town for ten days, and on April 20th, the last heavy piece of artillery fell silent.

This refitted 92nd quickly became known as the “Rainbow Division” and found itself on the western flank of the offensive in April 1945. Side by side, Buffalo Soldiers and Nisei advanced once more through the hilly countryside toward Massa, avoiding the roads pre-sighted by German guns. On April 5th, they reached Castello Aghinolfi, a 9th-century castle recently turned into one of the most formidable positions in the German defensive line with bunkers, strongpoints and gun emplacements. 2nd Lieutenant Vernon Baker from Iowa led a handful of his men in a charge against three enemy machine guns and an observation post, taking out their occupants. He then set up his own heavy weapons detachment in an exposed position, drawing enemy fire and covering the evacuation of American wounded. On the night of the same day, he led a battalion through minefields and heavy fire and helped secure the division’s objective. As 1st Lieutenant Fox, he initially received the Distinguished Service Cross, and only was awarded the Medal of Honor 53 years later at the same ceremony, the only living recipient, at age 78. During the following days, the 370th held on to the area surrounding the castle and supported the advancing 442nd Combat Team, who moved up next to it, destroying German resistance nests and bunkers. When more troops were needed to push on, the 473rd came up to protect the left flank against German counterattacks. On April 9th, American tanks first rolled into the outskirts of Massa, but were halted by fierce resistance. The Nisei outflanked the defenders on the Eastern side, finally forcing the Germans to concede defeat and abandon the town the next day. The Nazi lines were thinning, and despite moving their reserve into position around Massa, they could not prevent Allied guns and tank destroyers coming into range of La Spezia. Americans and British shelled the town for ten days, and on April 20th, the last heavy piece of artillery fell silent.

The 92nd Division did not idle after finally achieving their elusive objective. Soldiers of the 370th took Castelnuovo to the west of Massa on April 20th and planned to link up with the 442nd in Aulla, some 30 miles to the northwest in order to cut off any retreating Axis forces. Four days later, the 473rd moved into La Spezia, after Italian anti-fascist partisans had whittled down German resistance. On April 27th, Genoa was taken from the Germans, and the 370th and 442nd Regiments captured two enemy divisions on their way to safety beyond the Cisa Pass, less than a week before a ceasefire brought an end to the fighting in Italy.

After the Fighting and Decorations

In an ironic twist, segregation visibly caught up with the soldiers of the 92nd Division shortly after victory in Italy had been achieved. In Bagni di Lucca and Pisa, military policemen put up signs in the streets surrounding army hospitals, explicitly putting them “off limits to 92nd Div Troops”, purportedly for the safety of the white nurses. The Italian population, on the other hand, welcomed the black soldiers far more warmly. One soldier from the 370th Regiment recalls: “In Italy I felt safer than in Alabama. It was a fascist country, it was where the Mafia came from, but I didn’t feel my personal safety was in jeopardy there as it was in Alabama.” What must have felt like another insult were instances of German POWs being treated more equally to the victors than the black soldiers who had helped bring about their defeat. “When my unit was waiting to ship out, German POWs were there, doing various kinds of duties. We, the black officers, could not go to the white officers’ club. The German POW officers could.”

After the war, the African American servicemen returned to the United States and a society that insisted on segregation. One cannot help but wonder what had motivated the volunteers to join the armed forces of a country that treated them as second-class citizens, or what kept the draftees fighting after experiencing bigotry and condescension from their superiors. Of course, it stands to argue that their service contributed to a burgeoning civil rights movement, or at least made the discrepancy more visible between America’s fight against oppression and the regime of segregation at home. Veterans themselves have given various answers as to why they fought so readily:

"I was just fighting ‘cause I got orders to fight. I wouldn’t fight for no glory or nothing. I didn’t think I was gonna get a better shot at life, ‘cause I knew you couldn’t get a job when you got back."

"I was fighting trying to get back home. Alive."

"We believed that we were going to make our mark in this war, and really be able to claim our rights when we returned to the States."

It would be another three years after the end of the Second World war before President Truman issued Executive Order 9981, officially ending discrimination and segregation in the Armed Forces of the United States. It took until the late 1960s to fully integrate white and black soldiers into mixed units throughout all branches of service.

Although the division had been regarded as an experiment from the outset, often criticized by its superiors and pelted with racist outbursts, the numbers tell a clear story. 2,848 soldiers out of the division’s 13,000 men were killed, wounded or captured during its eight months in Italy. They captured 24,000 enemy soldiers and were awarded almost 3,300 decorations, including two Medals of Honor and 1,891 Purple Hearts.

Using the 92nd Infantry Division in Bolt Action

Based on the 92nd Infantry Division’s historical record, the 92nd Infantry Division set offers players various options to put the outfit on the gaming table. Of course, you can build your whole American army for Bolt Action from these kits, and lead the all-black regiments into battle on their own, representing the division as it fought in the first months of its tour in Italy. Other Warlord Games products, however, provide other possibilities. The Nisei set enables players to set up a joint force of plastic soldiers from the 92nd Infantry Division soldiers and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, as they would have fought in the spring of 1945. Throw in some GIs to represent the former flak gunners of the 473rd, and you got yourselves your very own “Rainbow Division”. Conversely, the troops from the Buffalo Soldiers set will also make a great addition to any existing American armies for the Italian theatre, as units from the 92nd Infantry Division were naturally attached to other formations, such as the 1st Armored Division.

New Rules: Legends of the 92nd

Forward Artillery Observer John Robert Fox (1915 – 1944)

“As the Germans continued to press the attack towards the area that Lieutenant Fox occupied, he adjusted the artillery fire closer to his position. Finally he was warned that the next adjustment would bring the deadly artillery right on top of his position. After acknowledging the danger, Lieutenant Fox insisted that the last adjustment be fired as this was the only way to defeat the attacking soldiers.

Later, when a counterattack retook the position from the Germans, Lieutenant Fox’s body was found with the bodies of approximately 100 German soldiers.“

Cost: 140pts (Veteran artillery forward observer)

Team: Fox and up to 2 other men

Weapons: Submachine gun, pistol or rifle/carbine as depicted on the model

Options:

Fox may be accompanied by up to 2 men at a cost of +13pts per man

Special Rules:

Danger Close:

All units (friend and foe, including Fox’s) that take at least one casualty from an artillery barrage called in by Fox, and are within 6 inches of his unit when the barrage takes place, is immediately wiped out and removed from play.

Final Protective Fire Plan:

Any artillery barrage ordered by the force containing Fox that is ordered when any enemy unit is within 12 inches of Fox’s position is granted a +1 on its result roll for the artillery barrage chart.

2nd Lieutenant Vernon Joseph Baker (1919 – 2010)

“When his company was stopped by the concentration of fire from several machine gun emplacements, he crawled to one position and destroyed it, killing three Germans. Continuing forward, he attacked an enemy observation post and killed two occupants. With the aid of one of his men, Lieutenant Baker attacked two more machine gun nests, killing or wounding the four enemy soldiers occupying these positions. He then covered the evacuation of the wounded personnel of his company by occupying an exposed position and drawing the enemy’s fire.”

Cost: 90pts (Veteran 2nd Lieutenant)

Team: Baker and up to 2 other men

Weapons: Submachine gun, pistol or rifle/carbine as depicted on the model

Options:

Baker may be accompanied by up to 2 men at a cost of +13pts per man

Special Rules:

Overwhelm:

When any unit in an army containing 2nd Lt. Baker assaults an enemy unit with the “Fixed” special rule, the assault counts as a ‘surprise charge’, regardless of the distance the assaults starts from.

Get Them to the Rear:

Any unit in an army containing 2nd Lt. Baker that is within 6 inches of a medic unit gets a bonus of +1 to its shooting rolls.