At the time of Italy’s entry into World War Two, she possessed a modern and – on paper at least – highly effective fleet. Four battleships and eight heavy cruisers were available, with three more battleships being fitting out. However, there were no aircraft carriers, not least because the Regia Marina was intended to operate near to friendly air bases in Italy and Africa.

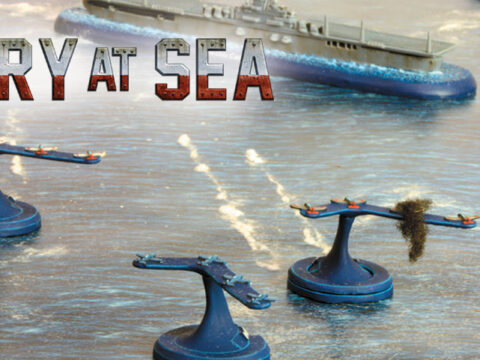

As might be expected from a force operating among the islands of the Mediterranean, light forces were quite numerous, including 14 light cruisers, 128 destroyers and 62 motor torpedo boats, which was a weapon favoured by the Italians and well suited to local conditions. No less than 115 submarines were available. The main Italian naval base was at Taranto, home of the battleship force. Lighter groups were based out of ports on the Italian mainland, Sicily and the Red Sea.

The Regia Marina was primarily tasked with interrupting British logistics and trade through the Mediterranean, and with keeping the Axis nations’ links to North Africa open. Major actions with the Royal Navy were not desirable nor really necessary for this mission to be carried out.

This defensive mindset was reinforced when British torpedo bombers attacked the Italian battle squadron in port, sinking one ship and putting two others out of action.

Efforts to interrupt Allied troop and supply movements were made by the Regia Marina, leading to the Battle of Cape Matapan in 1941. After initial successes the Italian force began to withdraw, only to come under attack from British carrier aircraft. The attacks slowed the lone Italian battleship and crippled a cruiser, allowing the British surface forces to catch up and sink the crippled cruiser and two more heavy cruisers.

The defeat at Matapan further dented Italian morale, and subsequently the surface fleet behaved timidly throughout the rest of the war. Sorties were made, but these tended to evaporate in the face of resistance, which allowed overmatched Allied vessels to drive off Italian forces that should have destroyed them with ease.

The long campaign to sustain and reinforce the island fortress of Malta resulted in bitter air and sea battles, such as the Second Battle of Sirte. A powerful Italian force including a battleship and two heavy cruisers came out to cut Malta’s lifeline, and it fell to a force of cruisers and destroyers to prevent the massacre of the merchant ships.

The response from the light British covering force was aggressive but should not have deterred a battleship force – the largest gun on the Allied side was of 6-inch calibre, matched against the 15-inch and 8-inch armament of the battleship and cruisers. Yet the Italians would not press the issue, behaving as if they were the ones under attack by the destroyers and cruisers, darting out of the smokescreen they laid to fire a few shots then vanish once again. A bold – cheeky, even – advance by the British destroyers, closing to attack with torpedoes, was perhaps the decisive factor. The Italian force opened the range and drew off, leaving the convoy unharmed but under heavy air attack. This behaviour was characteristic of the Regia Marina in World War Two.

Italian submarine forces operated in the Mediterranean and out of captured French ports against Allied shipping in the Atlantic. Some boats were specifically designed for commerce raiding. They were armed with more, but smaller, torpedo tubes than their peers. This allowed a larger salvo to be launched at a convoy, increasing the chances of a hit – the smaller torpedo was still more than adequate for sinking merchant vessels.

The Regia Marina failed to achieve much more during the course of the war, eventually surrendering to the Allies at Malta. Its personnel fought against their former allies towards the end of the war, losing a little over 4,000 men against Germany as opposed to just under 25,000 against the Allies.

It is interesting to speculate what the Regia Marina could have achieved had it been better led or handled. Italian enthusiasm for the war was noticeably lacking, and this led to lacklustre performances in the air, on the ground and at sea. The resulting reputation for lack of nerve is not deserved – Italian troops and ships at times fought bravely, especially for a commander or a cause they believed in – and in other wars of recent history there was nothing wrong with Italian courage or fighting ability.

It seems likely that, had the personnel of the Regia Marina really believed in their cause, their excellent battleships and cruisers might have covered themselves with glory. As Napoleon remarked: Morale is to the Physical as three to one.

Pre-Orders Coming Soon

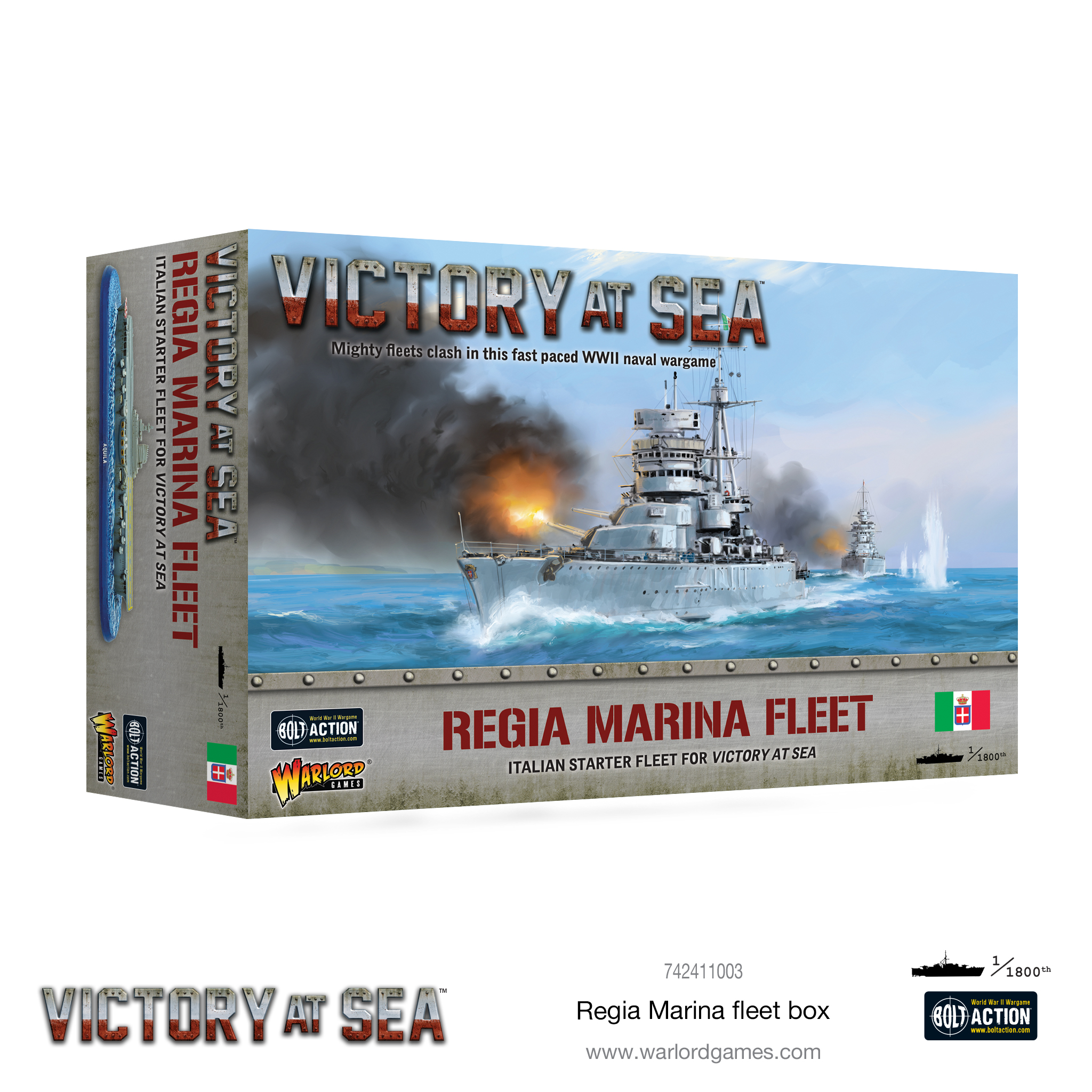

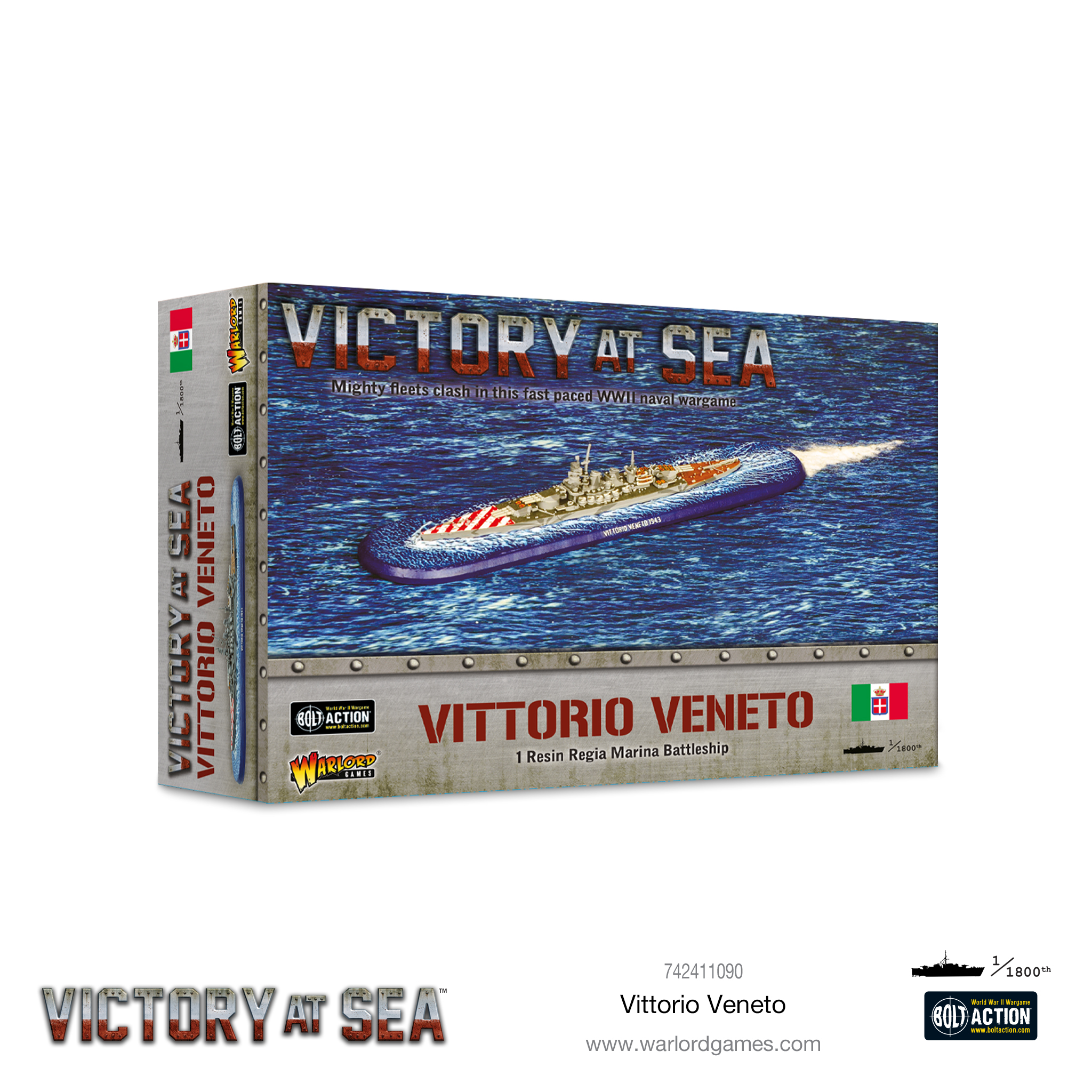

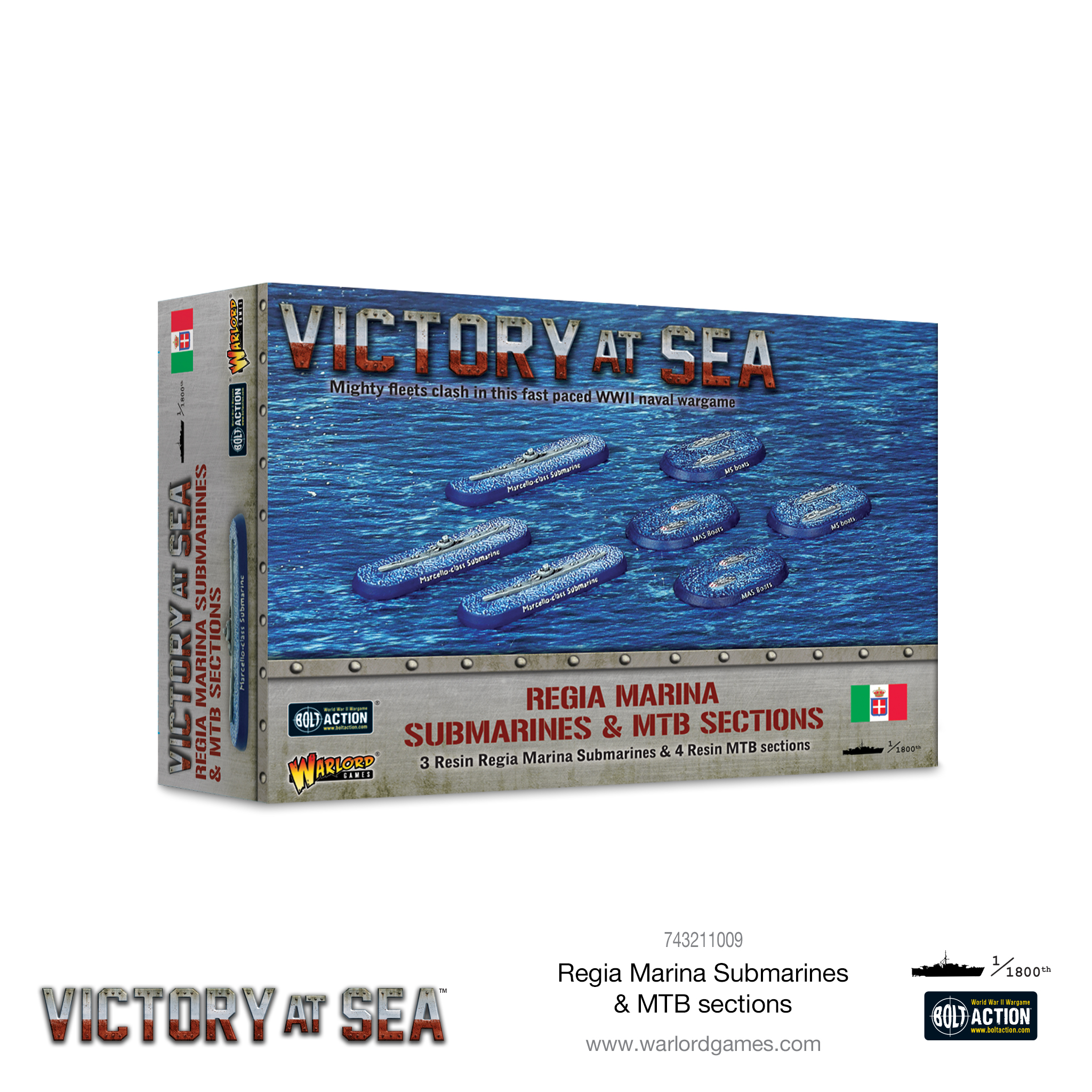

The Regia Marina in Victory at Sea comes to pre-order this weekend, with a starter fleet box, the battleship Vittorio Veneto, and the Regia Marina MTB sections and Submersibles box set available. You’ll also be able to net some money saving pre-order bundles.

Really curious as to the inclusion of the Etna CL in the Italian fleet. The Italian navy had relatively good ships in the Condottieri class light cruisers with 5 variations amounting to 12 ships including 2 each of the Montecuccoli, d’Aosta and Abruzzi classes that were quite good. Instead we have the Etna which was ordered by Thailand, never completed but taken over by the Italians and later the Germans. Never built, never sailed and scuttled in 1945. Given all the choices available, this seems puzzling?