Cavalry Charge and Counter-Charge

Lord Uxbridge, sensing the danger, unleashed the Household and Union heavy cavalry brigades commanded by Major General Edward Somerset and Major General William Ponsonby. The finest mounted cavalry in Europe pounced on the unsuspecting formations of the French. The Household Brigade led by Lord Uxbridge negotiated the sunken lane and moved along the line of the Brussels road. The men of the 1st and 2nd Life Guards, the Royal Horse Guards and the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards charged the 1st and 4th Cuirassiers of Dubois Brigade. While the French Horse had armour, the Guards cavalry had the advantage of surprise and impetus given to them by charging downhill, and the cuirassiers gave way after a sharp fight. The Household Cavalry pressed on, smashing into the 19th and 54th Regiments of Aulard’s Brigade, scattering four battalions of infantry. They continued forward past La Haye Sainte and were only checked when they came up against Schmitz’s Brigade in square formation at the bottom of the slope. The Household Brigade had wreaked havoc but was now a spent force, their horses being totally blown.

To the left of the Household Brigade the Union Brigade, so called as it contained regiments of English, Irish and Scottish dragoons, were only opposed by unsuspecting infantry. After negotiating friendly infantry battalions the Royal Dragoons smashed Bourgeois’ Brigade, Captain Kennedy Clark capturing the eagle of the leading battalion, that of the 105th Regiment, whilst Sergeant Ewart of the 2nd Royal North British Dragoons, the ‘Scots Greys’, captured that of the 45th Regiment (part of Nogue’s Brigade). The Inniskilling Dragoons charged and routed Quiot’s Brigade. Durutte’s Division fared better, having time to form square to fend off the attentions of some Scots Greys. The Greys, drunk with success, went out of control; though they should have been the reserve their commander now ordered an attack on the Grand Battery.

The Greys managed to cause mayhem amongst the gunners, but their blown horses were unable to escape a counter-attack. A well executed charge of ten squadrons of cuirassiers, five of lancers and three of chasseurs à cheval – two and a half thousand French horsemen in all – had the British ‘heavies’ right where they wanted them. Not only were the British a spent force, they were incapacitated by the heavy mud that had been caused by the churning of hooves. Both British heavy brigades were terribly mauled and were lost as a cohesive force for the rest of the day. Colonel Hamilton, commander of the Greys, lost his life for his impetuosity and was found the next day with both his arms cut off. Ponsonby also fell to the thrust from a sergeant of lancers.

Further pressure was alleviated when Vandeleur’s light brigade applied pressure that turned the French cavalry back to their own lines. Although many have since criticised the use of the British heavies in this way, it is worth reflecting that these brave men thwarted Napoleon’s main coordinated all-arms attack of the day. If this attack had succeeded, it would have surely broken Wellington’s centre and won France a famous victory. Instead 3,000 prisoners were taken, and countless equally brave Frenchmen lost their lives.

The Prussians Near

Napoleon had lost valuable time. Bülow’s Prussians were nearing the field of battle and the Emperor had committed Lobau’s VI Corps in full and two cavalry divisions to prevent the Prussians influencing the struggle for the ridge. Napoleon had to win the battle quickly, but the whole army was already exhausted by its exertions.

The lull in the battle now gave the Prussians the chance to manoeuvre closer to Wellington’s position, though they slowed at the Lasne stream as they toiled with their guns. ‘Old Blücher’ urged his men to Herculean efforts “It must be done! I have given my word to my comrade Wellington. You would not have me break my word?” His men pushed on and shortly after four o’clock Prussian infantry were forming at the edge of the Bois de Paris, ready to assault Plancenoit.

Wellington’s army still clung to its ridge. Wellington busied himself reinforcing his centre, taking advantage of the respite whilst his aides kept careful watch for their Prussian allies. Napoleon meanwhile knew that time was running out for him. He needed to smash Wellington aside and snatch victory before he was crushed between the British forces and those of Blücher, but he was now starting to run out of men and options. D’Erlon’s Corps was not ready to carry on the fight; Reille was embroiled in the ‘diversionary’ attack on Hougoumont, whilst the static Lobau was protecting his right flank. The only reserve available was his Imperial Guard, the finest that the French could muster, over 10,000 elite troops. Napoleon loved his Guard, they were his children, and at this pressing time he hesitated at the thought of sending such fine regiments forward. They would win the day, but at the cost of thousands of lives. While the Guard were the cream of the French Army, they were also the key enforcers of Napoleon’s regime and their loss would in turn weaken his position in France. Whilst Napoleon dithered, Marshal Ney acted.

Ney’s Cavalry Advance

Ney had mistaken Wellington’s shoring up his centre, mixed with the movement of casualties and prisoners to the rear, as that of the Allied army beginning a precipitate retreat. It was time to send forward the heavy cavalry to complete the victory. What happened next was not only truly awe inspiring, but also terrible. Over the next two hours over sixty squadrons of French cavalry in twenty regiments assaulted Wellington’s ridge. Cuirassiers, lancers, carabiniers and chasseurs à cheval, lancers and Gendarmes d’Elite of the Imperial Guard, were supported by at least twelve artillery batteries. Nine thousand sabres were assigned to the attack, the first wave being led by Milhaud’s Cuirassier Corps, supported by Lefebvre-Desnouette’s Guard Light cavalry.

It was 4pm and 4,800 elite horsemen struck the Allied line between Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte. An hour later, Kellerman’s III Cavalry Corps and Guyot’s Guard Heavy Cavalry Division were also committed.

The brave Ney was at the forefront of every effort to sweep the ridge clear, so much so that during the attacks he had three horses killed under him. The French cavalry by no means attacked at the gallop as the steepness of the ridge, the mud and the bodies of their fallen comrades saw them reduced to a trot. The Allied infantry in turn formed square, allowing over seventy supporting French cannon to wreak havoc against these tightly packed blocks. But the cavalry still made no impression, and the French could not break a single square. On the French side the cavalry ran the gauntlet of British cannon fire, gunners discharging round shot, shell and canister into the waves of horsemen and then at the last moment running to the relative safety of nearby squares.

The battery of Captain Mercer, of Fuentes de Oñoro fame, was stationed between two Brunswick squares. The gallant Mercer and ‘G’ troop RHA believed that the Brunswickers were badly shaken. If they were to run back towards them then the Germans would flee the field, so Mercer kept his battery in action throughout, he and his gunners taking what shelter they could around the guns.

The French cavalry were repeatedly driven off by the steadiness of Wellington’s infantry, supported by counter-charges of allied cavalry. Ney could have destroyed the Allied army if he had utilised infantry to support the cavalry attacks. Both Tissot’s Brigade of Foy’s Division and Bachelu’s Division were available, but Ney did not employ them until it was far too late. By the time Tissot and Bachelu were ordered forward, the French cavalry had suffered crippling casualties and were exhausted. Over 6,000 infantry trudged up the slope, over the very ground that the cavalry had turned into a quagmire. The infantry were met by cannon fire and murderous musketry volleys; they quickly turned and ran, both Bachelu and Foy having been wounded.

More to come in part 4:

History: The Battle of Waterloo – part 4

Back to previous parts

History: The Battle of Waterloo – part 1

History: The Battle of Waterloo – part 2

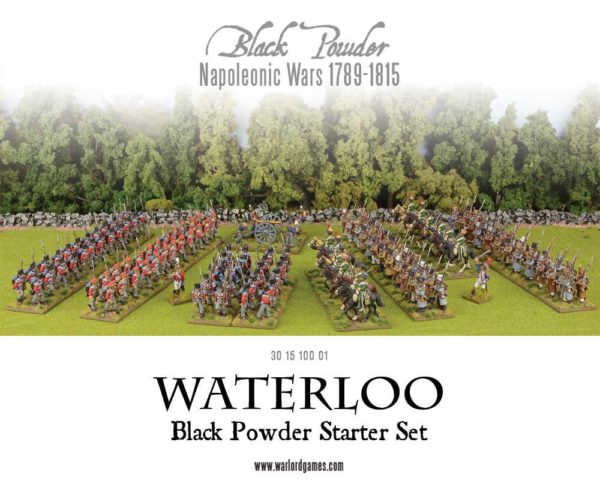

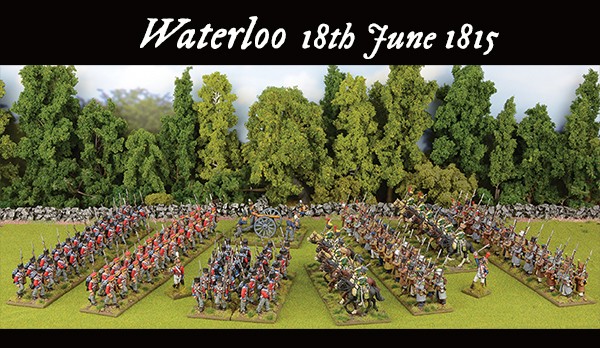

Begin your Waterloo!