Chris Brown is here again to teach us all about the accuracy of casualties within wargames by comparing reality to dice results…

Wargames casualty rates are almost invariably horrendous. In a real battle it may happen that an entire squad is wiped out by a shell, a mine or a particularly well-aimed burst of machine gun fire, but really that is relatively rare. On the other hand, even the best of squads or sections may be reduced to total ineffectiveness without any blood being shed; sheer exhaustion can be enough to remove the unit from the fight. The Bolt Action pinning mechanism can achieve this very effectively. It is perfectly possible for a unit – especially one which is in a building – to be rendered ineffective by a steady accumulation of pins but not have lost a single figure.

Wargames casualty rates are almost invariably horrendous. In a real battle it may happen that an entire squad is wiped out by a shell, a mine or a particularly well-aimed burst of machine gun fire, but really that is relatively rare. On the other hand, even the best of squads or sections may be reduced to total ineffectiveness without any blood being shed; sheer exhaustion can be enough to remove the unit from the fight. The Bolt Action pinning mechanism can achieve this very effectively. It is perfectly possible for a unit – especially one which is in a building – to be rendered ineffective by a steady accumulation of pins but not have lost a single figure.

Wargames losses are, generally, very heavy compared to real life, but we should, perhaps, think of the term ‘casualty’ in the very widest possible sense. This is not simply a matter of men who have been killed or wounded, but of all those no longer taking an active part in the battle. Some may have run out of ammunition, or had their weapon damaged or lost it during a parachute jump or a beach landing or in combat. If a squad has been under fire, the figures that we consider as casualties may be wounded and are being treated or carried by fellow-soldiers, thereby reducing the combat effectiveness of the unit; an individual may even have just lost his glasses and cannot see the enemy!

Wargames losses are, generally, very heavy compared to real life, but we should, perhaps, think of the term ‘casualty’ in the very widest possible sense. This is not simply a matter of men who have been killed or wounded, but of all those no longer taking an active part in the battle. Some may have run out of ammunition, or had their weapon damaged or lost it during a parachute jump or a beach landing or in combat. If a squad has been under fire, the figures that we consider as casualties may be wounded and are being treated or carried by fellow-soldiers, thereby reducing the combat effectiveness of the unit; an individual may even have just lost his glasses and cannot see the enemy!

We might also include men who are, in fact, still moving around with their comrades, but through shock, demoralisation or exhaustion are simply not making any contribution to the battle. Those men are still present in body, but are no longer functioning as part of the squad ‘team’. In fact a very large proportion of men who were absent from their section are probably not injured in any way at all; they have just become separated from their comrades. They may have genuinely lost touch with their squad in the smoke and confusion of battle, but they may just as easily have found a safe hole in the ground and decided to stay there. They will very likely find their way back to the squad in due course – they may good soldiers as a general rule, or even be particularly effective soldier on most days, but for today they’ve had enough…and who can blame them?

We might also include men who are, in fact, still moving around with their comrades, but through shock, demoralisation or exhaustion are simply not making any contribution to the battle. Those men are still present in body, but are no longer functioning as part of the squad ‘team’. In fact a very large proportion of men who were absent from their section are probably not injured in any way at all; they have just become separated from their comrades. They may have genuinely lost touch with their squad in the smoke and confusion of battle, but they may just as easily have found a safe hole in the ground and decided to stay there. They will very likely find their way back to the squad in due course – they may good soldiers as a general rule, or even be particularly effective soldier on most days, but for today they’ve had enough…and who can blame them?

In effect a great many of our ‘casualties’ are men who are only ‘out of action’ in a very immediate sense; temporarily dazed from blast or blinded by the flash of an explosion, but who may be able to return to the fight after a short period. It is just that a Bolt Action battle is of such short duration that they are no longer part of the game.

In effect a great many of our ‘casualties’ are men who are only ‘out of action’ in a very immediate sense; temporarily dazed from blast or blinded by the flash of an explosion, but who may be able to return to the fight after a short period. It is just that a Bolt Action battle is of such short duration that they are no longer part of the game.

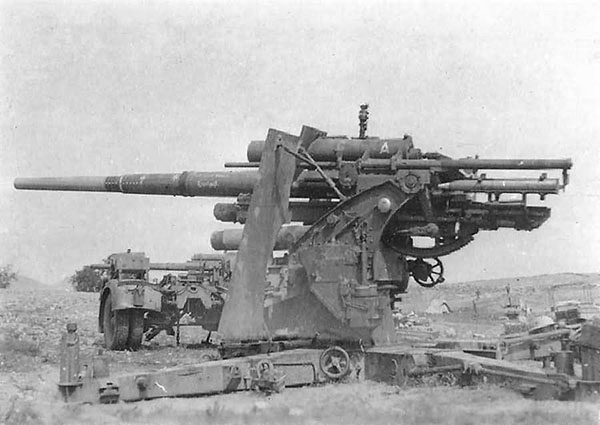

The same sort of consideration applies to vehicles. Tank losses were high in World War Two, but not so high as we might expect from what we read in soldiers’ memoirs or from what we see on the tabletop. The battle diaries of the British units that fought at Arnhem, for example, tell of a great many German tanks, assault guns and half-tracks being ‘knocked out’, but German records show a total of only 17 armoured vehicles lost over the nine days of fighting. The discrepancy comes about because of different views of what constitutes ‘knocked out’. For the airborne troops it would, essentially, mean any vehicle that had been eliminated from the current phase of action. That would include vehicles which had sustained a hit and had been withdrawn from the fighting or which had been abandoned by the crew, but for the Germans ‘knocked out’ would mean any vehicle which was damaged beyond repair. Since the Germans won the battle they were able to recover and repair vehicles which, in other circumstances, would have been lost irretrievably. Tanks are expensive machines and all armies go to great lengths to restore them to service so a tally of the number of tanks that were permanently lost is not a good guide to the number that were knocked out in action. A very large proportion of the vehicles that were put out of action suffered nothing greater than a lost track, a jammed turret or even a common-or-garden mechanical breakdown and were back on the battlefield in a matter of days or even hours.

What does this mean for Bolt Action players? In terms of a single game it means nothing at all. A wounded man or a damaged vehicle is out of the battle and that’s all there is to it, but in a series of linked games the implications are considerable. We should think of a least one third of losses as being recovered within 24 hours and another third being back in action within two or three days. Despite the enormous lethality of combat, the fact is that the most widely shared experience of battle is survival. Even among the infantry the majority of soldiers who served in World War Two – or any other war for that matter – managed to come through without ever suffering a physical wound, so the next time you see your cherished models stopping bullets don’t get too depressed about it; most of them have just gone to ground or run away!

Do you have an article within you? Are you itching to show your collection to the world of Bolt Action? Then drop us a line with a couple of pictures to info@warlordgames.com or share with all over at the Warlord Forum

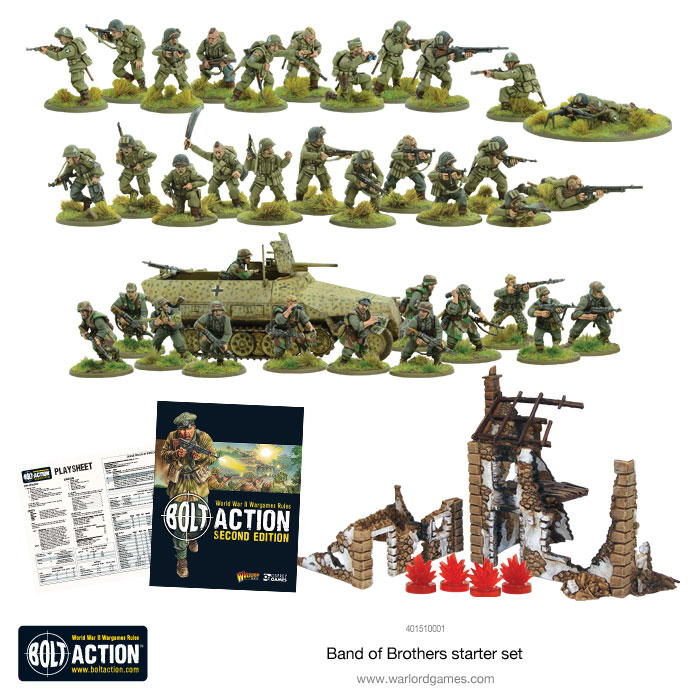

Get yourself started!