Introduction

Chariots developed out of earlier vehicles mounted on disk or cross-bar wheels, with the origin traced to the Near East, where spoke-wheeled and horse-drawn ‘true’ chariots are first estimated to originate the earlier part of the second millennium BC.

The early usage of chariots was mainly for transportation purposes. With technological improvements to their structure, such as a “cross-bar”, chariots were introduced in the military.

The Sumerian “Standard of Ur” depicts the earliest form of military wagon with four wheels drawn by four asses or ass/onager hybrids, with a driver and a warrior armed with spears and axes riding into battle over the corpses of the slain. Among the Royal Tombs of Ur where buried warriors and kings not only with their carts and wagons, but also with the draft animals and the driver.

The Egyptians invented the yoke saddle for their chariot horses in c. 1500 BC. Chariots were effective for their high speed, mobility and strength which could not be matched by infantry at the time. They quickly became a powerful new weapon across the ancient Near East. The best preserved examples of Egyptian chariots are the four specimens from the tomb of Tutankhamen. Chariots can be carried by two or more horses.

It spread into Asia Minor, Greece and was known in Northern Europe by 1500 BC.

However with the increase in horseback riding by 1000 BC, the chariot lost most of its military importance and were gradually replaced by the use of mounted cavalry.

The Egyptian Chariot

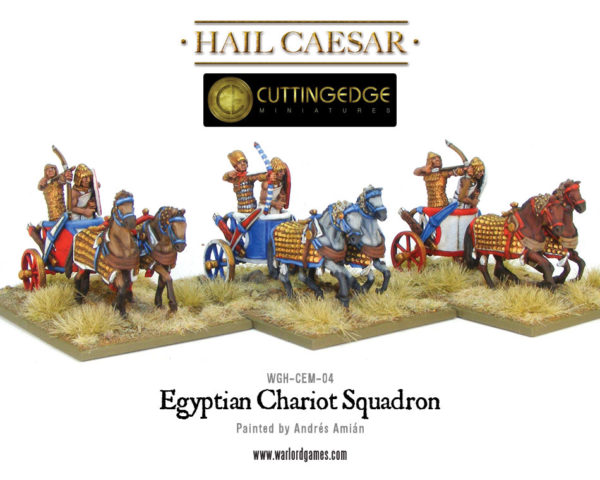

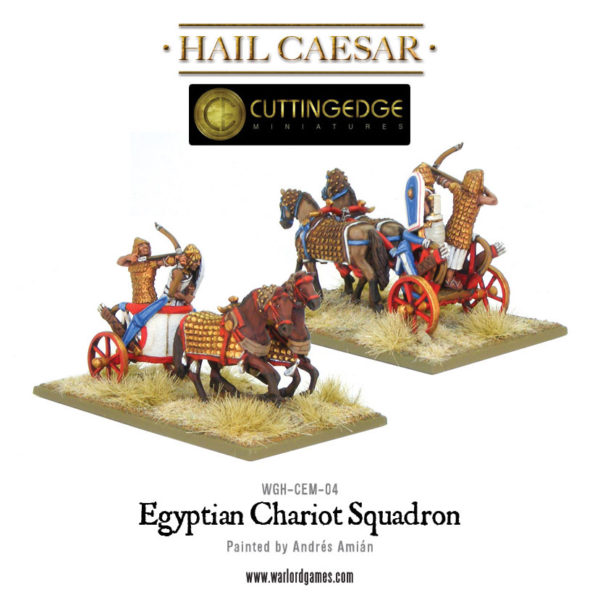

The Egyptian horse drawn chariot typically consisted of a light wooden semi-circular framework with an open back surmounting an axle and two wheels of four or six spokes.

Some analysis of ancient chariots provide that the Egyptians greatly improved the design of this vehicle. However, while they certainly did make improvements to certain parts of the chariot, it is arguable whether the Egyptian chariot was better, or simply designed for a different purpose and terrain than others in the Middle East. For example, the Egyptian chariot had a metal covering for the axes, which reduced friction, and this was certainly an improvement. Also, some wooden parts were strengthened by covering them with metal sleeves.

The Egyptians knew two types of chariots. These consisted of the four wheeled chariot which, by the late 18th and early 19th dynasties, were mostly abandoned for the superior six-spoke vehicles. The six-spoked wheels could be made lighter and were better supported than the heavier four-spoked wheels, making the whole chariot more reliable.

The spokes of the wheels were made by bending six pieces of wood into a V-shape. These were glued together in such a way that every spoke was composed of two halves of two V-shaped pieces, forming a hexagonal star. The tips of the V’s were fastened to the hub by wet cattle intestines, which hardened when they dried.

The tires were made of sections of wood, tied to the wheel with leather lashings which passed through slots in the tire sections. The thongs didn’t come in contact with the ground, making the chariot more reliable by reducing the wear and tear

Two horses were yoked to the chassis by saddle-pads that were placed on the horses’ backs. Leather girths around the horses’ chests and bellies prevented them from slipping. A single shaft attached to the yoke pulled the chariots.

The Chariot in Egyptian Warfare

Hittites used their heavy chariots to crash into the troops of their enemies. However, the Egyptian chariots were used fore more of a supporting role to the archers who manned them.

At about the same time the “cross-bar” form of construction gave way to the extremely light spoked-wheel. This gave the chariot even greater speed and maneuverability without compromising stability and strength.

War chariots were manned by a driver holding a whip and the reigns and a fighter, generally wielding a bow or, after spending all his arrows, a short spear of which he had a few.

In field action, chariots usually delivered the first strike and were closely followed by infantry advancing to exploit the resulting breakthrough, somewhat similar to how infantry operates behind a group of armed vehicles in modern warfare. This tactic was effective against tight units of spearmen as it allowed holes to be punched in a line which would otherwise be difficult to attack due to its compact nature. In another role, chariots were deployed to pursue and disperse enemies after the victory had been achieved. Egyptian light chariots contained one driver and one warrior, usually wielding a bow or, after depleting all his arrows, a short spear.

Serving in the charioteer corps did not come cheap. The recruit was allotted a team of horses from the royal stables and five attendants, whom he had to equip. The chariot itself cost him, according to a possible prejudiced scribe, three deben of silver for the shaft and five for the body, a small fortune, which only noblemen could afford. However, after the chariot was constructed, considerable work was needed in order to maintain the vehicle in good working order.

Hence, the chariot was of paramount social and political significance since it heralded the appearance of the chariot corps which consisted of a new aristocratic warrior class modeled on the ubiquitous Asiatic military elite known to the Egyptians as the maryannu (young heroes). The depiction of the triumphant New Kingdom pharaoh as a charioteer shows that the chariot was quickly absorbed into the royal regalia, becoming a powerful symbol of domination. Interestingly, the royal chariot itself was treated as a heroic personality with gods overseeing each of its named parts.

Disadvantages

Chariots were expensive, heavy and prone to breakdowns, yet in contrast with early cavalry, chariots offered a more stable platform for archers. Chariots were effective for archery because of the relatively long bows used, and even after the invention of the composite bow the length of the bow was not significantly reduced. Such a bow was difficult to handle while on horseback. A chariot could also carry more ammunition than a single rider.

The size and its dependence on the right terrain was another disadvantage of the chariot. Some scholars point out that chariots were vulnerable, fragile and required a level terrain thus making them unsuitable as a physical shock force.

Chariots were not able to launch sudden strikes because they made too much noise.

It is thought that early Egyptians may have had no experience of breeding and training horses for military purposes, which may be a reason why so few cavalry served in the Egyptian military.

Notable Battles

The best known and preserved textual evidence about Egyptian chariots in action was from the Battle of Kadesh during the reign of Ramses II; probably the largest single chariot battle of all time. You can read Nigel Stillman’s epic account of the battle here.

The Battle of Kadesh (also Qadesh) took place between the forces of the Egyptian Empire under Rameses II and the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II at the city of Kadesh on the Orontes River, in what is now Syria.

The battle is generally dated to 1274 BC, and is the earliest battle in recorded history for which details of tactics and formations are known. It was probably the largest chariot battle ever fought, involving perhaps 5,000–6,000 chariots.

Article written by Dino.S