When wargamers picture the armies of ancient Egypt it is usually the forces of the pharaohs of the New Kingdom that we have in mind. The New Kingdom refers to the years from the 16th to the 11th centuries BC – roughly from 1550BC until the death of Ramesses XI in 1070BC. This encompasses what today we call the Eighteenth, Nineteenth and Twentieth dynasties and the reigns of such famous warrior pharaohs as Amhose I, Thutmose III, Seti I, Ramesses II (aka Ramesses the Great) and Ramesses III. This whole period of Near Eastern history is also known as the Late Bronze Age or LBA – a term originating amongst archaeologists but nowadays often used widely to refer to these distant times.

This is the age when Egypt aspired to empire and fought numerous wars for control of the region that lay between Egypt and the Mitanni Empire (based in south-east Anatolia and northern Syria) and the Hittite Empire (based in central Anatolia and later extending south and east into Syria). The battleground between them – Amurru in the north and Canaan in the south – encompassed the lands that now form western Syria, Lebanon and Israel. The Egyptians and their rivals sought to gain control of the many wealthy cities in this region, forging alliances, making treaties and creating client states whose rulers paid tribute – at least nominally – to the Great Kings of the Hittites and the pharaohs of Egypt. It is a rich era for wargamers, with a variety of interesting well-match opponents and colourful armies of infantry and chariots.

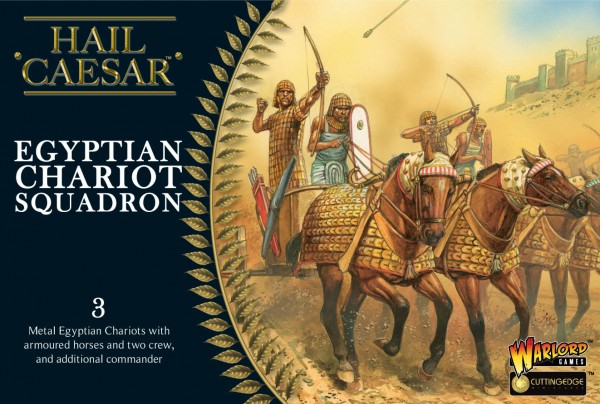

Scholarly tradition suggests that the chariot was introduced into Egypt during the preceding years of disunity and foreign rule known as the Second Intermediate Period. During this time Egypt was fragmented into a number of rival kingdoms. The northern Delta region was ruled by a Canaanite dynasty called the Hyksos or ‘shepherd kings’. It may well be that the chariot was introduced, or at least rose to prominence, during the time of the Hyksos. In any case, the battle chariot emerges as the prime weapon of warfare during the New Kingdom, featuring in armies from the time of Amhose I’s conquest and reunification of Egypt. For those swayed by such things, it is interesting to note that many Egyptian words relating to the construction and use of chariots betray a foreign origin, whilst decorative motifs such as date palm branches and opposed facing animal heads are also typical Syrian features. Regardless of its origins, the Egyptians soon mastered the construction and deployment of chariots, developing a fighting platform that was light, strong and ideally suited to their needs.

When describing the wars of these distant times it is useful to think of the three dynasties of the New Kingdom as three separate and distinct phases.

During the Eighteenth Dynasty (1543-1292BC) the Egyptians ran rampant over the Near East. The armies of Thutmose III – dubbed the ‘Napoleon of Ancient Egypt’ -even raided over the Euphrates and pillaged the lands of the Mitanni. The pharaohs of this time brought the many kingdoms of Canaan and southern Syria into submission. A series of tributary buffer states were established throughout the Levant. Towards the end of the dynasty, pressure from enemies led to these states realigning with the Hittites or reneging upon their tributary status. Eventually this roused the last pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty to defend their interests. The young pharaoh Tutankhamun may well have perished during such a conflict. The pathology of his mummy suggests a speeding chariot struck him after he was knocked to the ground. Towards the end of the Dynasty the man who was probably Tutankhamun’s father, the so-called Heretic Pharaoh Akhenaten, initiated a series of monotheistic religious reforms that caused much unrest and eventually led to his downfall. His reign is known as the Amarna period after Tell el-Amarna where the ruins of Akhenaten’s capital Akhetaten were found. With the death of Tutankhamun the royal line effectively died out, and an elderly court official called Ay occupied the throne. Another courtier and general of Akhenaten’s time Horemheb followed Ay’s brief reign. Horemheb did much to restore order to a troubled land. He re-established the worship of the old gods, eradicated the monuments and memory of Akhenaten’s time, and – most propitiously – chose another military man Ramesses I as his successor

The succeeding Nineteenth Dynasty (1292-1187BC) saw the Egyptians back in the driving seat once more. The first pharaoh of this age was Ramesses I. Ramesses’mummy was famously sold by nineteenth century tomb robbers and ended up as part of a carnival of curiosities in Niagara North America. It was eventually identified and repatriated to the Cairo museum in 2003. In life Ramesses was less well travelled, preferring to stay at home and entrust military affairs to his son and successor Seti I. During the time of Seti and his son Ramesses II (Ramesses the Great) the Egyptian Empire reached its greatest extent. This was an age of almost constant warfare against well-armed and organised enemies, especially the Hittites, and dangerous new foes such as the Sea Peoples. Ramesses II fought the famous battle of Kadesh – almost certainly the biggest chariot battle of all time – against a coalition of Hittities and allied Syrians led by the King of Kadesh. The story of the battle is recorded in two inscriptions to be found captioning carved representations of events at Abydos, the Temple of Luxur, Karnak, Abu Simbel and the Ramesseum. There are also papyrus records referring to the battle. Letters in the form of clay tablets were found in the archives of the Hittite capital recording a subsequent exchange on the subject. All in all, this makes Kadesh the first battle in history to be described in detail, complete with the numbers involved, even if we are somewhat at the mercy of Ramesses when it comes to the facts of the matter.

The Nineteenth Dynasty ended with a period of dynastic strife and rebellion that was brought to an end by a new pharaoh Setnakhte, founder of the Twentieth Dynasty (1187-1077BC). Although Setnakhte was able to restore order, he and his descendants ruled during times of almost constant decline amidst growing outside pressures, most notably from the seaborne raiders and migrants the Egyptians called the Sea Peoples. The only pharaoh of the dynasty to rise to fame was Setnakhte’s son Ramesses III, who defeated the Sea Peoples in a great sea battle and campaigned twice against the Libyans in the Western Delta. Ramesses left many impressive monuments to posterity, but significantly his funerary temple at Medinet Habu was the first temple situated in the core territory of Egypt to feature extensive fortifications. It is a sign of troubled times amidst the grandiose statements of imperial glory. Food shortages, economic decline, tomb robberies, and internal strife dogged the end of the New Kingdom. Ramesses III himself was murdered in a palace conspiracy, and his successors were embroiled in domestic issues. Nine pharaohs – all called Ramesses – ruled duringr a period of just over a hundred years. Egypt’s influence and dominions slipped away. In the reign of the final pharaoh of the dynasty Ramesses XI the Egyptian state disintegrated into anarchy.

The end of the New Kingdom coincides with the period that we call the Bronze Age collapse, during which invaders overran the Near East, casting to ruin many old and previously powerful kingdoms. During the following years Egypt became divided into numerous petty realms. The pharaohs of the immediately succeeding Twenty-first Dynasty ruled from Tanis in the north-eastern delta, whilst the priesthood of Amun at Thebes controlled middle Egypt. It was the beginning of the Iron Age, and the glorious days of Egyptian Empire were gone forever.