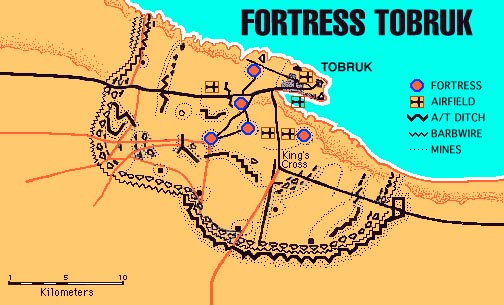

Tobruk was the one rock that stood firm against Rommel’s inexorable advance in the desert. Churchill urged that the port should be held “to the death without thought of retirement.” From the 10 April to 27 November 1941, the forces defending Tobruk stood firm against Rommel’s surrounding troops.

General Morshead, commander of the mainly Australian garrison until their replacement by Polish and British units in the autumn of 1941, declared that “there will be no Dunkirk here. If we should have to get out, we’ll fight our way out. There is to be no surrender and no retreat.”

Rommel was convinced that the port would soon fall. But the 9th Australian Division would not give him his prize without a stiff fight. British officers regarded the Australian defenders with disdain as an ill-disciplined rabble, but instead they proved formidable and courageous fighters, led by Major General Leslie Morshead, known as ‘Ming the Merciless’ to his men due to his strict and demanding style of leadership.

The German assault on Tobruk began on the night of 13 April. Despite heavy losses, Rommel threw more of his men at the defences, but these again were hurled back by the rifle fire, anti-tank guns and strong artillery of the tenacious defenders. While this attack was taking place, Rommel sent several units against the Egyptian border, almost 100 miles away, where they were met with resistance by the 22nd Guards Brigade. Rommel quickly gained a reputation as a commander who could be ruthless with the lives of his troops – he dismissed Generalmajor Streich of the 5th Light Division for being overly protective of the men under his command.

Rommel seemed to be everywhere at once, directing his men from the thick of fighting, racing between his scattered troops, often in his own personal reconnaissance plane.

On 30 April, reinforced by the 15th Panzer Division, Rommel attacked Tobruk again, and again suffered heavy losses, particularly among his tanks. By this time, ammunition was beginning to run low among the Axis forces. Just as had happened to the British following their initial successes with Operation Compass, the Axis forces were in danger of overstretching themselves. Both sides faced immense problems with supplying their troops in the desert from their base of operations. Between Tripoli and the front at Tobruk was a distance by road of almost 1,200km; from Cairo to Tobruk, 800km. Shipping across the Mediterranean was harried by attacks from enemy navies (particularly submarines) and air forces.

Meanwhile, the land that both sides had to traverse was bleak, inhospitable desert, with few settled areas, which provided very little opportunity to forage. Rommel’s advantage was that the British forces were still reeling from their defeat in Greece. Coupled with the loss of the 2nd Armoured Division’s tanks, the British feared the German commander’s superiority in armour. This was offset by Operation Tiger, which managed to ship almost 300 Crusader tanks and over 50 Hurricanes by convoy through the Mediterranean in early May, with the loss of only a single transport. Before these reinforcements arrived, Wavell launched Operation Brevity on 15 May, in a combined attack by British and Indian troops, but the attackers were swiftly outflanked by Rommel, and pushed back beyond the Halfaya Pass, just within the Egyptian border.

Undeterred, and bolstered by the arrival of the new tanks, the British mounted another offensive on 15 June – Operation Battleaxe. Again the British enjoyed early successes, retaking Halfaya Pass, but again they were soon pushed back when Rommel’s panzers once more outflanked them. The Afrika Korps suffered heavy casualties, but the British lost more tanks and aircraft, which were much more difficult to replace than men. While Rommel was promoted by a delighted Hitler, Wavell was replaced by General Sir Claude Auchinleck, whom Churchill hoped would instil a more aggressive fighting spirit in the British army of North Africa.

The intense heat of the North African summer put paid to any intentions that the generals of either side had of offensive action. In their trenches, plagued by flies and sand-fleas, the infantry from both sides suffered from a lack of sufficient water. By day they scorched, by night they froze. Military action was reduced to a few skirmishes along the Libyan border. Meanwhile the Axis forces continued to batter at Tobruk with artillery and bombing raids. Throughout the summer of 1941, the British 70th Division grimly held on to the port, reinforced by an Australian brigade, a Czech battalion and a Polish brigade. They were supplied the bare essentials by the Royal Navy, braving the heavily shelled harbour. In contrast, Rommel’s supply line from Europe was constantly harassed by Royal Navy submarines and RAF raiders based in Malta, and many Axis ships ended at the bottom of the Mediterranean, including several troop transports bearing reinforcements.

The Rats of Tobruk

The defenders of Tobruk were the first soldiers to stop the German forces in the North African campaign. Lord Haw-Haw, during his notorious radio broadcasts, contemptuously referred to them as “poor desert rats of Tobruk.” The 9th Australian Division who garrisoned the port proudly adopted this nickname and even designed their own rat-shaped medals, crafted from scrap metal taken from a German bomber that they had downed with a captured German gun.

During the initial stages of the siege of Tobruk, the Rats concentrated on reinforcing their defences, and true to their name, constructed a warren of tunnels down which they could hide during air raids or artillery bombardment. As the siege progressed, the Rats began to take the fight to the besieging Germans, creeping out to capture an enemy soldier for interrogation, or making audacious night attacks to cause as much damage and panic as possible without getting caught.

A Rat patrol would crawl for several miles to reach an enemy position, quietly surround it, then rush it with bayonets, often capturing their objective without a shot being fired. After an epic nine months under siege, the Rats were finally all withdrawn from Tobruk by October 1941, many reluctant to leave the job unfinished. This was a political decision, pushed by the Australian government which was keen to have all Australians in the Middle East fight under a unified command, as well as the concerns of Australians back home that the division had suffered too long without reinforcement.

During their stay at Tobruk, the Australians had suffered 3,000 casualties, with over 900 men taken prisoner. Their stubborn resistance was proof that the German army was not all-conquering at a time when Hitler’s forces otherwise dominated every other arena of war.

This is an excerpt from our latest Bolt Action theatre book, ‘Duel in the Sun’ – which covers not only the campaign in North Africa, but also the fighting in Italy. The book is packed with new units, characters, scenarios, and environmental conditions to add more options and narrative to your games…not to mention your very own Rat of Tubruk Figure. For more information, take a look at Alessio Cavatore’s guide here.

If you’re looking to dive head-first into Desert warfare, take a look at our Duel in the Sun Platoon offers!

British 8th Army Platoon

Your first stop for the British in the desert is the highly detailed plastic set from Perry Miniatures:

Your choices include:

German Afrikakorps Platoon

If it’s Rommels famous DAK you favour then here’s your starting point. Again a set from Perry Miniatures with 38 detailed plastics:

Your choices include: