Dr Roger Pauly is an expert on all things Napoleonic Portuguese, so to celebrate the release of our brand new Portuguese artillery pieces, we asked him to write an article on the history of the Portuguese army during the Peninsular campaign.

Dismal Times

Roger: March 17, 1809, was not a good day for Portuguese Lieutenant-General Bernardim Freire de Andrade. He had recently taken command of his country’s largest army and was under orders to stop a French invasion led by the formidable Marshal Nicolas Soult, advancing into Portugal from Spain. However, de Andrade felt his nation’s frontier was indefensible, so three days earlier he had ordered a retreat to the town of Braga.

Unfortunately, an excitable militia made up much of his rag-tag force and these men easily fell prey to rumours. Among such tales were allegations that their senior general was a secret French traitor or that he intended to flee and desert his army. Now at Braga, these troops mutinied and placed de Andrade in prison under guard.

The initial plan was to give him something of a trial, but later that very afternoon the mutineers reinforced themselves with alcohol and a local peasant mob. They returned to the prison and forced de Andrade’s guards aside. The mutineers dragged the hapless general outside the prison and allowed him a brief last confession before unceremoniously stabbing him to death. For good measure, the same mutineers shot de Andrade’s chief of staff, General Custodio Jose Gomas Vilas Boas, the following day.

In subsequent years, a number of historians have defended de Andrade; however, it never looks good for a general when his own troops killed him. Moreover, it turns out that murdering your generals leading up to a battle may also have been a poor idea as the French swept the Portuguese from the field at the disastrous Battle of Braga on March 20, 1809.

How did things come to such a low point for Portugal?

The acting Regent of the kingdom, Crown-Prince Joao had heroically fled with his family halfway around the world to Brazil during an earlier French invasion led by General Jean-Androche Junot in 1807. Before leaving, the Regent placed the administration of his government in the hands of a ‘Junta’ or governing council. To clarify Junot = a French general, Junta = the Portuguese government. Unfortunately, armed resistance largely collapsed once the Royal family had fled. The victorious French rounded up the most competent members of the Portuguese troops, enlisted them into Napoleon’s service, and sent them off to Central Europe.

Through the murky see-saw of changing political and military tides that typified the Peninsular War, the French position deteriorated by August 1808. A notorious cease-fire (the Convention of Cintra), allowed Junot and his men to leave Portugal with their weapons and large amounts of looted Portuguese booty. The agreement even provided them with transportation back to France, courtesy of the British Navy.

Enter Beresford

Portugal had a long history of enlisting foreign military commanders and in the wake of Junot’s invasion, the Junta recognized that their kingdom desperately needed help. They formally asked for a British commander to take control of the Portuguese army, preferably Arthur Wellesley who had been instrumental in weakening Junot’s position. Wellesley, the soon-to-be Duke of Wellington, turned down the job in lieu of serving as the supreme allied commander in Portugal. They eventually selected Major General William Beresford and named him “Marshal of the Portuguese Army.”

At age 40, the relatively young Beresford was one of two ‘natural’ sons of the Marquess of Waterford and had a reputation as someone good at training troops. Beresford was also friends with Wellesley, could boast of an impressive service record, and spoke passable Portuguese. Despite his suitability for the role, it seems Beresford was initially unenthusiastic. As he recalled, “The choice was not left to me, and the first thing I was told was that it was not optional.”

Beresford was selected in February of 1809 and he arrived in the capital of Lisbon in early March. Unfortunately, this was too late to save the unlucky generals de Andrade and Boas from their fate 200 miles to the north in Braga. While Wellesley set about defeating Soult and this second French invasion, Beresford wasted no time initiating his reforms of the Portuguese forces.

The New Portuguese Army

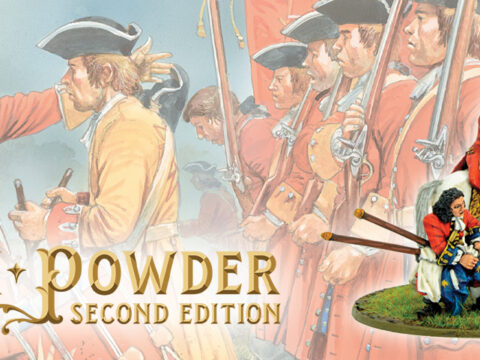

Thanks to an existing conscription system, Beresford could recruit significant numbers of men. The challenge he faced was turning them into an effective fighting force. The initial British opinion of the Portuguese Army was not favourable as one commentator described its organization as a “monstrous hodgepodge.” As for its personnel, another observer characterized them as “Portuguese cowards, who won’t fight 1/16th of a Frenchman with arms, but murder and plunder the wounded.” Others criticized the army’s lack of basic hygienic practices as well as its elderly, corrupt, and often-absent officer class.

One of Beresford’s first reforms involved recruiting British officers into the Portuguese Army. He felt that their better discipline could serve as a model for the local troops. Officers in the British army were encouraged to join the Portuguese with the offer of an automatic step-up in rank. Thus, by simply enlisting in Beresford’s force a captain earned an instant promotion to major with an accompanying increase in pay. Some 300 British officers took this option over the course of the Peninsular War.

Beresford was careful to spread these men out and to avoid over-favouring them. He did not wish to stir up any nationalist resentment from the Portuguese. For any given number of British officers enrolled at a particular rank, a reasonable number of Portuguese officers likewise gained the same rank. For example, a typical five-company battalion would have three British company commanders, each with a Portuguese second-in-command and two Portuguese company commanders, each with a British second-in-command. It should be noted that the quality of the Portuguese officers was greatly improved as well. In only four months after taking command, Beresford and his staff dismissed 215 officers and ordered another 107 to retire. In addition, the officers and enlisted men saw their pay increased by 80-100% depending upon rank.

The British also issued the Portuguese Army smart new uniforms and thousands of reliable Brown Bess muskets. Some units of specialized light-infantry skirmish troops known as Caçadores (Portuguese for ‘hunters’) were eventually given the prized Baker rifles made famous in Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe books and television series. The Portuguese did not just receive new weapons, but their British officers likewise taught them how to march and fight according to the British manual of drill.

Show Me the Money

Perhaps it goes without saying that to raise, pay, clothe, equip, feed, and train an army that eventually grew to about 50,000 men was an enormous financial undertaking. The Portuguese Junta overhauled its taxation mechanisms as best as it was able, but there was a drastic shortfall caused by the devastation of several key provinces thanks to the successive French invasions. In 1809, the Portuguese government estimated that it could only pay 57.55% of the cost of a war effort that was consuming 81.3% of its budget. Wellesley put the situation in the following terms: “Portugal supports more than four times her former military establishment, with half her former revenue.” This situation forced London to pay a heavy subsidy to Lisbon in order to keep her ally in the war. Between 1808 and 1814, Portugal received nearly eleven million pounds, which was a fair bit of coin in those days.

Unfortunately, much of this currency passed through the Portuguese government, which used these funds neither wisely nor effectively. Instead of providing its troops with silver for commissary purposes, the Junta issued units nearly worthless paper script or bothersome promissory notes that merchants had to submit directly to the government for reimbursement. This meant that civilians with food and supplies were much more inclined to sell provisions to British units rather than their fellow Portuguese. As a result, Portuguese soldiers were habitually under-fed and this often forced Wellesley to provide rations for them directly. Portuguese troops’ pay was frequently in arrears as well.

These two issues were major contributing factors to a high desertion rate that continually plagued recruitment for much of the war. For example, between January 1810 and June 1811 the Portuguese Army enrolled 15,520 new recruits. Not bad, yes? However, in that same period, the army suffered 10,400 desertions! Once a recruit had become accustomed to his unit the likelihood of his deserting dropped, but the idea that service = starvation remained a serious bar to recruitment. Still, enough men stayed in the army that throughout most of the Peninsular War anywhere from a half to a third of Wellington’s army was Portuguese.

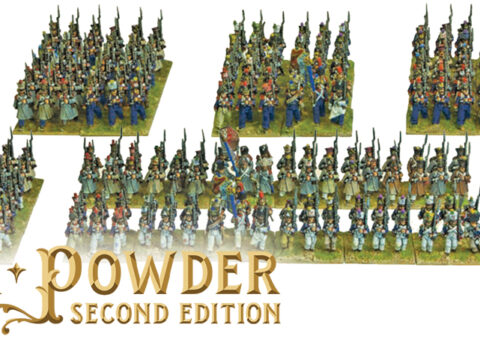

Organization and Appearance

Beresford re-organized the new Portuguese Army into twenty-four line regiments, most of which put two battalions in the field. In addition to this, there were six of the Caçadores battalions mentioned above and their numbers were doubled to twelve. On paper, there were also supposed to be twelve cavalry regiments of about 7,000 mounted troopers but in reality, Portugal never raised anything close to that number. There was an excellent reason for this failure. According to an 1808 survey, there were only 6,516 horses in the entire country!

Other branches of service included the artillery, now organized into four regiments. There was likewise a large national militia of ninety-six battalions called the Ordenanças. Regrettably, their regional nature mitigated their sizable numbers. By longstanding tradition, these units were designed for local defence only and were spread evenly across the country. As such, they were of little use when the war shifted into Spanish territory. Their training was also abysmal as was their equipment: often pikes in lieu of firearms. Still, they could perform marginally well when holding fortifications or operating as guerrillas against French supply lines.

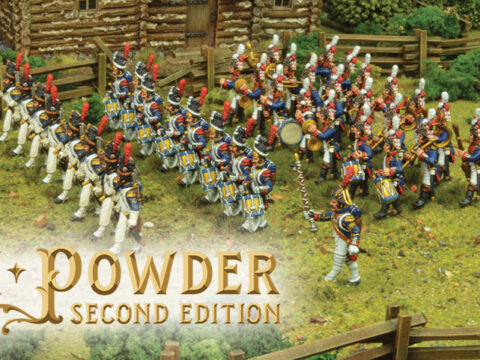

Painting the Portuguese

The basic line infantry uniforms were dark blue and became progressively more like British uniforms in cut and design as Britain’s involvement became more and more extensive. Like their British counterparts, the coat had a relatively short cut, the leathers were white and the shako was of the ‘stovepipe’ design. Some units eventually began wearing shoulder wings, not unlike those worn by British flank companies.

The facings varied from regiment to regiment with the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 13th, 14th, and 15th wearing white. The 4th, 5th, 6th, 16th, 17th, and 18th sported red while yellow facings were worn by the 7th, 8th, 9th, 19th, 20th, and 21st respectively.

Lastly, the 10th, 11th, 12th, 22nd, 23rd, and 24th wore light blue. Piping did not follow this pattern. Instead, regiments 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19 and 22 had white piping while regiments 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, and 23 wore red. Everyone else used yellow. Thankfully, all companies wore white plumes, so hopefully, that makes the painting job a little easier.

Appropriately enough for their role as skirmishers, Caçadores wore a shade of brown that some commentators described as dark and others as light. In all likelihood, the colours simply faded over time in the Iberian sun. Elite companies within the Caçadores were known as Tiradores and they wore a black plume while everyone else wore green. Tiradores roughly translates as ‘marksmen’ and so these were the men most often issued the coveted Baker Rifles mentioned above.

Caçadores wore black belts and their piping was typically green. Like the line infantry, they sported a plethora of different facings based on the units in which they served. After 1811, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions, as well as the 7th Battalion wore black collars with light blue, scarlet, black, and yellow cuffs respectively. The 4th, 8th, and 11th Battalions wore sky blue collars with sky blue, black and scarlet cuffs. Scarlet also graced the collars of the 5th, 9th, and 12th Battalions as it did the cuffs of the 5th and 12th. The 9th however, wore black at the end of their arms. Lastly, the 6th and 10th Battalions sported yellow collars with yellow and black cuffs respectively.

Cavalry also wore the standard Portuguese blue uniform much like the line infantry with a similar variety of collar and cuff colours. For headgear, the men wore black leather helmets up until 1810 and shakos afterwards. Please keep in mind that most Portuguese cavalrymen did not actually get to wear a horse under their legs, as noted above. Many of them thus had to be assigned to garrison duty. Artillerymen also were garbed in the standard blue coat but with black facings and red piping. Belts and headgear likewise copied the line infantry.

As for the Ordenanças, there is less agreement today about the uniforms of this glorified militia. Apparently, they initially wore a green outfit with red elements, but later many switched to the popular new blue. There is also evidence that certain units wore brown. At one point London sent Beresford 20,000 grey uniforms he did not want so it is probable that he passed a number of these off to the Ordenanças too. It is also entirely likely that a many of their members simply wore civilian clothing.

Results

So with all this money, effort, new organization, and Beresford’s leadership, how did the Portuguese Army actually perform? The short answer is remarkably well.

They first saw action in May of 1809, only a few months after Beresford’s arrival. At this early point, they failed to impress Wellesley. He grumbled, “The men are very bad; the officers worse than anything I have ever seen.” The troops were sent back to camp for further months of intense training. By early 1810 Wellesley, now entitled The Duke of Wellington, felt the Portuguese were starting to become an effective force and were ready for minor operations.

Later that year at the Battle of Busaco in September, the British impression of the Portuguese soldier began to change for the better. Beresford’s new line battalions performed steadily and played an important part in this victory. The élan of the Caçadores was particularly impressive. One British observer noted, “Whenever the Caçadores got a successful shot, they laughed uproariously as if skirmishing were a great source of amusement to them.”

By 1811, Wellington was speaking of the Portuguese troops as being able to manoeuvre as well under fire as British soldiers did. At Albuera that year, a Portuguese brigade in line formation and under artillery fire repulsed a charge by four regiments of heavy French cavalry without having had time to form square. That sort of thing just did not happen very often in the Napoleonic era.

Over the next few years and across hundreds of campaign miles, the Portuguese reputation only continued to grow. At the time of Battle of Vitoria in June of 1813, they were arguably as effective as the British soldiers. Even the ferocious General Thomas Picton, who did not suffer fools gladly, wrote, “there was no difference between the British and Portuguese troops, they were equal in their exertions and deserving an equal portion of laurel.” Wellington began calling the Portuguese “the fighting cocks of the army.” He was referring to roosters, of course.

Although they never lost their reputation for poor hygiene, the Portuguese soldiers were particularly good at weathering the hard-life of campaigning. One British observer writing at about the same time as Picton claimed, “The Portuguese regiments, who behaved in the field as well as any British did, or could, are on the march, though smaller animals, most superior. They were cheerful, orderly, and steady. The English troops were fagged, half tipsy, weak, disorderly and unsoldierlike; yet the Portuguese suffer greater real hardships.”

This is a remarkable comment. Keep in mind that the British Army was an exceptionally-tough force. Its formidableness was limited only by its small size, yet man-for-man it was one of the best (if not the best) in Europe. Yet here we have a British writer arguing that the Portuguese soldier could perform on the battlefield as well as a British soldier and was even better on the march!

Later at the siege of San Sebastian, one of the last major actions in Spain, Portuguese troops again performed astonishingly well. British Officer George Hennell, wrote “It is impossible for troops to have behaved better than the Portuguese did…They were up to the middle in water, grape…and musketry mowing down full half of the first regiment that advanced, and yet they did not hurry or spread, but marched regularly to the breech…to the admiration of all spectators. One must wonder if perhaps Portuguese troops by late 1813 might not have been the finest regular (i.e. non-Guard) line and light infantry in the world. When the war finally ended in April of 1814 with actions at Toulouse in France, about a third of Wellington’s force was still comprised of his loyal and fierce Portuguese soldiers.

Perhaps one of the greatest and most lasting testimonials to the skill and fortitude of the Portuguese Army and Beresford’s success came after the Peninsular War had ended. In the late spring of 1815, Wellington once again found himself facing hostile French forces, only now he was in the cold, rainy fields of northern Europe far from familiar Portugal. The Iron Duke immediately made a request for 12,000 to 14,000 Portuguese troops to aid him in the impending fight. When asked who should take command of the Anglo-Allied Army in event of his death in the upcoming campaign, Wellington recommended Beresford.

In the end, the French Emperor moved too fast to allow such a transfer before the Battle of Waterloo, but it speaks volumes that Wellington tried once again to call on the brave and bloodied Portuguese Army and its great reformer. Perhaps Waterloo would not have been such a ‘near run thing’ if Wellington had his Fighting Cocks with him.

For Additional Information and Reference, see the following.

- Costas, Fernando Dores, “Army Size, Military Recruitment, and Financing in Portugal During the Period of the Peninsular War, 1801-1811,” E-Journal of Portuguese History 6, No 2, (Winter 2008), 1-27.

- Costas, Fernando Dores, “The Peninsular War as a Diversion, and the Role of the Portuguese in British Strategy,” Portuguese Journal of Social Sciences, 22 (2013), 3-24.

- Esdaile, Charles, The Peninsular War: A New History, New York: Plagrave, 2003.

- Glover, Michael “A Particular Service: Beresford’s Peninsular War” History Today 36, (1986), 34-38.

- Glover, Michael, “Beresford and His Fighting Cocks,” History Today 26, (1976), 262-268.

- Griffith, Paddy, ed., Wellington Commander: The Iron Duke’s Generalship, Strettington: Antony Bird, 1983.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip, The Napoleonic Sourcebook, New York: Facts on File, 1990.

- Newitt, Mayln, “The Portuguese Army” in Gregory Fremont-Barnes, ed., Armies of Napoleonic Wars (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2011), 178-192.

- McNabb, Chris ed., Armies of the Napoleonic Era (Oxford: Osprey, 2009).

- Muir, Rory, Tactics and the Experience of Battle in the Age of Napoleon, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Portugal on the march!

There’s never been a better time to start a Portuguese army in Black Powder. The army bundle gives you everything you need to get started, including a cannon and some keen-eyed Caçadores.