Tensions on Hawaii

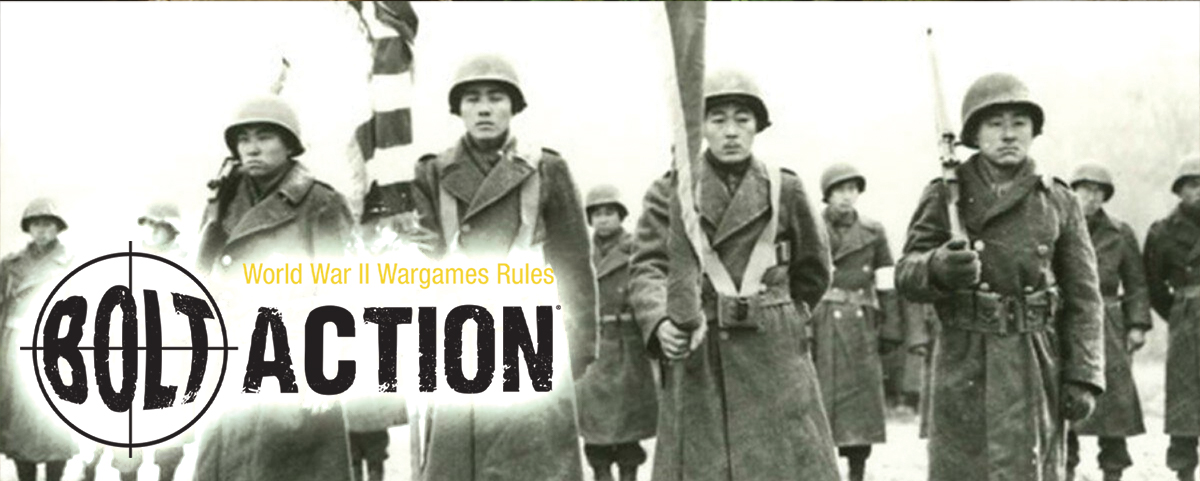

December 7, 1941 was a sudden shock to the United States and shone a spotlight on the previously unassuming American territory of Hawaii. Here, as far as the American government was concerned, was the frontline in the war for the Pacific and it was inhabited by 158,000 Japanese – 37% of the total population. Could these foreigners be trusted to side against their homeland, betray their ingrained loyalty to the Emperor and stand up with Americans? The US government decided that in the short term the answer was no. This wasn’t a knee-jerk reaction to the events at Pearl Harbour, however. Over the last decade tensions had been building between the Japanese-American population and the white inhabitants. Some of these tensions stretched back even further.

The Japanese arrived in Hawaii starting about 1885 as plantation workers. Sugar companies hired them on contract as cheap labour, and the Japanese saw it as a means to save and create a comfortable life for themselves back in Japan when their contract was up. Many did not return home, however, and because there were no legal restrictions on what jobs the immigrants could take after their contracts were up (unlike in the continental US), many branched out starting farms and businesses. These families prospered and brought with them Japanese culture and traditions, established Japanese media, watched Japanese films and listened to Japanese radio. They even established their own social clubs. Initially, the white minority that governed the islands were not worried, feeling that the children of the Japanese, the Nisei (literally Second Generation), could be taught to be American.

Their parents taught them traditional values at home, including self-discipline, restraint, respect for authority, and to repay all obligations to others. What worried the businessmen and government of Hawaii, however, was that these children may also be indoctrinated into total loyalty to the Emperor, as was traditional. Fears about the Nisei began to rise alongside the military tensions of the 1930s. Japanese-Americans openly supported the militarism of Japan by purchasing Japanese War Bonds, sending home scrap lead and other materials and supplying funds for care packages for Japanese soldiers in Manchuria. In light of these actions, the Japanese of Hawaii were viewed through a lens of suspicion and fear. Newspapers in Hawaii began running stories that questioned the loyalty of those with dual citizenship, fearing they were actively spying for the Emperor and would sabotage American military installations.

This attitude generated resentment among the Nisei, who publicly argued that they were born American, raised American, and educated as Americans. When critics pointed out that there were still many Japanese in Hawaii who held dual citizenship, the Hawaiian Japanese Civic Association pointed out that the system for renouncing Japanese citizenship was a tangled bureaucracy that moved very slowly. They even tried to spur reform by creating a petition for a faster, simpler process in November 1940. While there were only an estimated 20,000-30,000 dual citizens according to 1938 figures, more than 30,000 signatures were secured by the end of December. This still wasn’t enough to quiet the suspicions of non-Japanese, particularly the US Navy and US Army in Hawaii. The general attitude of Hawaiian Nisei is best summed up by a 1939 Honolulu Star-Bulletin article written by a Nisei graduate of the University of Hawaii:

It is strange, however, that so much stress is laid on the dual status of Japanese-Americans when there are countless numbers of Americans of European nationalities in the United States who are in the same double category as Japanese-Americans. The patriotism of European-Americans, for the most part, is taken for granted. To this same group of hyphenated Americans, as well as 100 per centers, Japanese-Americans must prove their loyalty to Uncle Sam.

Expatriation will help in dissolving much of the suspicion surrounding the Japanese-Americans, but it is doubtful whether that distrust can be completely stamped out, even if it is possible for every one of the 120,000 Japanese-Americans to sever his political bonds with Japan. Nothing short of war between the United States and Japan, and visible proof of patriotism by the Japanese-Americans in that war, will convince doubting Thomases of the Niseis’ allegiance to the country of their birth.

The article’s author would be proven correct in just two short years with the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Surprise Attack and American Reaction

Early morning on Sunday December 7, 1941, 183 planes of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) attacked American military assets in Hawaii as part of the first wave. They were followed closely by a second wave, a further 171 planes. In conjunction with the air attack, IJN submarines launched midget subs to torpedo ships in the harbor and provide intelligence. By the end of the day, the attack sunk or damaged 14 warships, more than half of which were battleships, destroyed or badly damaged 347 American planes, and killed more than 2,300 people. The raid cost the IJN relatively little, just 5 Type A midget submarines, 29 planes and 65 men.

The raid had far greater reach than the immediate military costs, however. The Japanese of Hawaii, who were already viewed with great suspicion, began to be arrested en masse by Army & Navy Intelligence officers. By the evening of December 8, 370 Japanese-Americans had been arrested as suspected collaborators. Alongside the mass arrests, General Short was made military governor of Hawaii, and ordered that all “enemy aliens”–meaning Japanese-Americans–could not change occupation or residence, or otherwise move from place to place without approval. They were further ordered to turn in all implements of war, fireworks, cameras, and short-wave radios, while all Japanese language schools, newspapers, and broadcasts were shut down. These harsh conditions were further compounded with a curfew on the Japanese. General Short ordered that public announcements be worded to suggest Japanese loyalty, even if no one really trusted them.

The first step toward allowing Japanese military service came shortly after, however. General Short ordered that the ROTC be called up to form the Hawaiian Territorial Guard. When he was informed that many of them would be Japanese, he responded that “he thought they might prove perfectly loyal”. Despite this opinion, on January 21, 1942, 317 Japanese-American members of the Territorial Guard were discharged without reason. This coincided with the all-Caucasian Businessmen’s Military Training Corps being officially recognized as a paramilitary force and tasked with watching the local Japanese.

Lieutenant General Eamons, who had replaced Short as military governor of Hawaii, felt that given the chance to prove their loyalty, the Americans of Japanese Ancestry (AJA), as they insisted on being called, could be a valuable asset. On May 12 he recommended that all AJAs in uniform should be formed into a single special battalion and shipped to the mainland for training. His recommendation received no immediate response, but on May 26 the Japanese 298th and 299th Infantry, former National Guard units, were pulled off the defensive line in Hawaii and confined to Schofield Barracks. Eamons repeated his recommendation in light of this order, and just two days later his plan received approval.

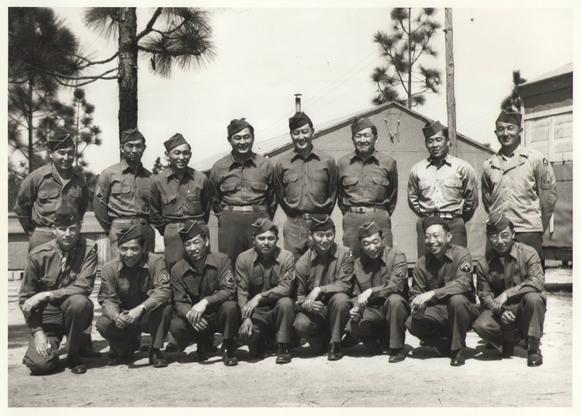

He was ordered to form a single battalion, over strength if necessary, but keep all weapons and vehicles in Hawaii before shipping the unit to the mainland. The War Department orders emphasized that the men were to be ensured they were not being interned and would be issued new equipment as needed. The battalion was organized on May 29 under the command of a Caucasian World War I veteran, Lt. Colonel Farrant Turner. As an island native and former National Guard officer he had a high opinion of the Japanese and relished the opportunity presented to him. The new battalion was tentatively designated the Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion and boasted 29 officers and 1,300 enlisted soldiers. Turner came to respect the soldiers under his command, most notably that they were all striving to be first-class soldiers. Even the enlisted riflemen studied books on troop leadership and tactics, on their own initiative. Turner was instructed that under no circumstances were Japanese to be placed in command of any of the rifle companies but was allowed to make four officers in his headquarters. By the time this special battalion set sail for California on June 5, there were 1,432 men under Turner’s command.

Training on the Mainland

The Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion arrived in Oakland, California and learned they had been redesignated as the 100th Infantry Battalion. To the AJA men, this was a sign that Army Command didn’t know what to do with them, and it made them feel like they were being discriminated against. Typical battalions were numbered 1 through 3 and subordinate to a Regiment, and so the designation as the 100th showed all that they were ‘special’. This led to the wry adoption of the unit’s nickname One-Puka-Puka. Puka was the Hawaiian word for ‘hole’ and was also used as slang for the number zero.

In Oakland the 100th were loaded onto troop trains bound for Camp McCoy, Wisconsin. Upon arrival, further orders designated the 100th as a ‘Separate’ battalion, meaning that they were not part of any regiment and would not be integrated with a Caucasian regiment. Along with this order, Central Defense Command stated: “Every effort must be made to maintain morale and esprit de corps in the unit at a high level. So far as possible, officers and men must be made to feel that their unit is an honored element in the Army and that it is being trained with a view to its ultimate employment in combat.”

Despite their ambivalent position in the Army, the men of the 100th pushed themselves hard during training. They wanted to prove that their battalion had the best soldiers in the US Army, rather than just the only Japanese soldiers. Further, without the typical support assets of a regiment Turner needed to train his own anti-tank, transport, and support personnel. As a result, by August 1, 1942 the battalion’s Order of Battle consisted of one Infantry battalion of four rifle companies, two extra rifle companies, one battalion medical section, one battalion service section, a transportation platoon, and a service company. To help organize and command this over strength unit, Turner requested 12 new officers. Even these new men were impressed by the AJA soldiers, one remarking two months later that “[he’d] rather have a hundred of these men behind [him] than a hundred of any others [he’d] ever been with.” Another of them was taken by surprise when he learned that his subordinates had spent $8 of their own money to purchase the two volume Tactics and Techniques of Infantry.

The battalion’s officers were quick to learn that not only were the Japanese soldiers driven to perform, they were also an indispensable asset when it came to matters of leadership. As such, Japanese-American junior officers and non-commissioned men were included in staff briefings and consulted on matters of morale and discipline. This served not only to increase the unit’s efficiency but also prepared these junior men for greater leadership responsibilities in the future. Colonel Tuner, despite his orders, fully intended to promote a Nisei officer to company command as soon as one proved qualified, and then square the decision with Army Command afterwards. As it stood, because the men were so intelligent and motivated, two soldiers were trained for each officer position in the battalion, grooming ready replacements when the time came.

The men also came to greatly respect their officers, who would resolutely defend their men to other officers, including superiors, and would not allow those outside the unit to speak ill of the Nisei. Colonel Turner even corrected other officers when they referred to his men as ‘Japs’ or ‘Japanese-Americans’, supplying the preferred term Americans of Japanese Ancestry. This protective attitude was based not only in fostering unity, but also in the superior performance of the AJA soldiers. One heavy weapons officer boasted that the Army training manual gave 16 seconds to set up a heavy machine gun for firing, but some of his boys could do it in 5!

The progress of the 100th seemed to adequately prove Japanese-American loyalty, as on December 16, 1942, Army Command decided to allow them to enlist for service in Europe. A regimental combat team (RCT) would be formed, designated the 442nd, and initially it was thought that the 100th Battalion would form the core of this new regiment. The formation of the 442nd was officially announced in Hawaii by General Eamons on January 28, 1943, and within the next few weeks nearly 10,000 Americans of Japanese Ancestry signed certificates of their intention to enlist. With the huge numbers of volunteers, the plan to use the 100th as the new regiments core fell by the wayside.

On December 31, 1942 the 100th Battalion was ordered to Camp Shelby in Mississippi for more training and was attached to the 85th Division for training purposes. One cold, rainy morning, General Haislip of the 85th Division watched the 100th train and was thoroughly impressed. Later he commented to his officers, “I watched the 100th Battalion the other morning, and they’re better than some of our units that have been training a lot longer. It was rotten weather, too, but they played the game.” Despite this high praise, the men of the 100th had several more months of training to look forward to.

April 13th Hawaiian Japanese volunteers of the 442nd began arriving at Camp Shelby, and after the initial organizational period, experts from the 100th served as advisors and training officers, with platoons of the 100th demonstrating combat manoeuvres.

The battalion finally received their colours come July 20th, after a protracted struggle between Turner and Army Command. Months earlier, upon arriving in Camp McCoy, the men had selected the motto “Remember Pearl Harbor” and had drawn up a unit shield that bore the Hawaiian ape leaf and the yellow feather helmet that had been worn by Hawaiian chieftains. Turner accepted their designs and submitted them to Command but received notice that the unit’s motto would be “Be of Good Cheer” and its emblem a red dagger. Over the following months, Turner emphatically argued for the emblem and motto his men had chosen, and finally prevailed.

The end of July was cause for celebration for other reasons, as well. The order restricting Japanese from command of rifle companies was rescinded and Captains Taro Suzuki and Jack Mizuha were placed in command of Companies B and D. By this point 16 of the battalions’ commissioned officers were Nisei, 10 of which were 1st Lieutenants.

On to Africa and Beyond

The 100th Battalion were finally being mobilized. On August 11th they boarded trains for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey to prepare for the Atlantic crossing. Ten days later the men boarded the James Parker, a former tourist and banana boat, bound for Oran in North Africa. Alongside the 100th on the Parker was a general of Field Artillery, his staff, and one of his battalions, all of which were unarmed. As they neared Africa, the general sent on of his men to Turner to request the 100th’s weapons in case of an air attack. Turner sent the man back with his response: “If there’s any shooting to be done, we’ll do it ourselves.”

The Parker arrived in Oran on September 2nd without incident and sent to camp near the city. Local Army HQ suggested that the 100th be deployed guarding the railway in the desert from bandits, which Turner was not keen on; his boys were ready for a fight. Upon hearing about their fighting spirit, General Ryder of the 34th Division Turner and offered combat duty. He’d been impressed by the rumours that these Japanese-Americans wanted onto the frontlines, even though they’d live longer guarding trains.

The men were excited to be part of the 34th, as it was regarded as real fighting unit, reputed to be the first sent overseas by the US Army. Over the next two weeks, the veterans of the Division drilled the 100th in German tricks and tactics, passing on their hard-earned knowledge. The drills came to an end September 19th when the division, 100th Battalion included, embarked on a convoy to join the Italian Campaign.

Arriving in Italy on September 22nd, the 34th Division joined the Allied Fifth Army and began the advance on Rome. The 100th Battalion was temporarily attached to the 133rd Regimental Combat Team, replacing 2nd Battalion, who were on special duty. The RCT advanced southeast to Eboli, then on to Contursi and finally turned north to Montemarano.

On September 28, the 100th had their first casualty. Sergeant Tsukayama was hit by shrapnel from an anti-tank mine detonated by a passing Jeep. He also set a precedent, becoming the 100th’s first ‘reverse AWOL’, escaping from the field hospital to return to his unit. Many more Nisei men would follow his lead, using the excuse of “Da boys need me.” That same day they also got their first taste of combat and suffered their first losses. Departing from Montemarano on the Avelino Road, Company B was serving as regimental advance guard. Around 10am, 3rd platoon rounded a curve in the road and came under heavy fire from machine guns, mortars, and cannons that had zeroed in on the road. Sergeant Joe Takata turned to his men and announced, “It’s the first time, so I’m going first,” before advancing toward one of the machine gun nests firing his Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). A German shell exploded near him, and shrapnel struck him in the head, dropping him to the road. Despite his grave wounds, Sgt. Takata held on until his men crawled near enough that he could pass on the German’s positions. Intense fighting followed, and by the end of the skirmish another Nisei lay dead and seven were wounded. For his bravery under fire, Takata posthumously received the Battalions first medal, a Distinguished Service Cross (DSC).

Less than a month later, the battalion was embroiled in their first full scale conflict. On October 20th they were ordered to assault the 29th Panzer Grenadiers at Sant Angelo D’Alife. The German positions were well fortified and boasted excellent observation posts for artillery. Company A led off the attack at 1900 and made first contact with the enemy around 2230. The leading elements came upon a farmhouse, saw a brief flash of light as the door opened, and seconds later machine gun fire filled the valley. In the opening minutes 10 men were killed and 20 more wounded. Seeing that there was no cover from the German positions, Turner ordered his men to fall back to safety and called for mortar fire on the machine gun nests. During the retreat, PFC Thomas Yamanaga covered his squad’s retreat with his BAR, silencing one of the German machine guns before finally being cut down. He was posthumously awarded a DSC. Nearby, Private Satoshi Kadota, a medic, belly crawled through the fight to treat twelve wounded soldiers. Private Donald Hayashi stepped up and took command of his squad when the sergeant was wounded, and single-handedly covered their retreat for two hours. Lieutenant James Vaughn crawled through the fight to encourage his platoon, while wounded, and covered their retreat with his carbine. These actions, and many others at Sant Angelo, earned Silver Stars. Turner was finally ordered to pull his men out and let 1st Battalion of the 133rd RCT take up the attack. Eventually the 1st was also beat back, and the entire next day was spent reorganizing and preparing for a renewed assault.

The 100th was redeployed to capture Hill 529, near Sant Angelo, and Companies A and C pressed the attack on October 24th. Atop the hill were the ruins of an old castle which the Germans used to great effect. When darkness fell, Companies E and F moved up to relieve A and C, keeping pressure on the stubborn German lines. Come morning, the men of the 100th manoeuvred around the hill to attack from the northwest, behind the castle. The Germans made one last sally forth from the castle midmorning, but were repelled by the 100th and 1st battalions, supported by over 200 shells from the 100th’s 81mm mortars. Fearing complete encirclement, the German forces began a full retreat at noon which allowed the Americans to secure Sant Angelo. After five days of fighting, the Americans had advanced seven miles. This small victory had cost the 100th dearly; 21 killed and 67 wounded.

From Sant Angelo D’Alife, the 100th fought in several engagements including Ciorlano, La Croce Hill near Cerasuolo, and Mont Majo, which formed part of the Winter Line. While much heroics were to be had in these battles, none compared to Cassino. On January 24th, the 100th Battalion was ordered to advance on one of the most heavily fortified positions in all of Italy. Here, over just a couple weeks of fighting, the unit earned its nickname as “The Purple Heart Battalion”.

Cassino, Anzio, and Rome

Cassino formed the lynchpin in the Germans’ Gustav Line. The Todt Organization, Germany’s military engineering contractor, had spent months starting in October 1943 to fortify the mountains and valleys of the Gustav Line. Reinforced concrete pillboxes were installed, bunkers were chiselled out of solid rock, heavy artillery and machine guns placed in the mountains to sweep away any allied assault. At Cassino they destroyed any houses that were of no use and fortified the rest with stone and logs. Roads and other alleys of advance were heavily mined, barbwire laced with explosives guarded every German position and even Italy’s Rapido River was mobilized for the fight. The Todt engineers dammed the river, flooding miles of farm land under water up to two feet deep. To keep the water from draining they built a dike 7 to 12 feet tall paralleling the river bank. The dike was then topped with barbwire to discourage scaling. The river embankments themselves were 14 feet high and covered with aprons of mined barbwire to hamper attempts to climb down to the river bed, which had also been lined with barbwire and mines. All trees and brush had been removed to keep open firing lines but stumps up to three feet tall remained to hinder tanks. To top if all off, under the mud and water of the fields the Germans had placed mines every five feet with tripwires running off in all directions. To hamper the allies even further, on top Monte Cassino was an ancient Benedictine monastery. Allied command, to preserve the monastery and its relics, ordered that no bombardment of Monte Cassino was to take place.

On January 24th, the 133rd RCT, including the 100th Infantry, was ordered to assault the Gustav Line at Cassino and capture, among other targets, the Italian barracks, situated in an old castle, at Monte Villa. To reach their objective, the men of the 100th would have to advance across the flooded farmland, scale the German dike, climb into the dry river bed, advance the 75 feet to the opposite embankment, scale it, cross the fortified road at the top and charge at German positions in the village. Kicking off the attack was an artillery barrage at 2330, with the troops advancing at midnight. Men of the Ammunition and Pioneer platoon advanced ahead of Companies A and C, clearing and marking a safe path through the minefield. One such soldier, Sergeant Calvin Shimogaki, had his mine detection equipment disabled by German bullets, and so crawled through the mud feeling for tripwires with his bare hands, successfully clearing a path five feet wide and fifty yards long, earning a Silver Star for his bravery. As the 100th advanced, 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 133rd were stopped dead by a combination of the minefield and heavy German fire, prompting Company B of the 100th to be ordered into the fight at daybreak. Major Clough, the 100th’s CO after Turner had been hospitalized, refused the order and was relieved of command. Smoke was laid to cover the advance, but the wind direction changed and quickly revealed Company B to German gunners. Eleven men fought through to their position at the Rapido River dike, while many more took cover until nightfall. Under cover of darkness, the survivors of Company B regrouped, with some retreating to safety and others reaching the dike. As Allied plans to capture Rome hung in the balance, Companies A and C were ordered to across the river bed but were unable to advance past the west bank.

Over the next three days the 100th was pulled back and put in reserve while men from the 1st and 3rd Battalion renewed the assault, with little luck. By February 8th little ground had been gained, so a new plan was drafted. Working in concert with the 168th RCT, the 133rd was to pivot southwest and flank the German defenders. The 100th would be at the outer edge of the arc, and thus have the farthest to travel. Under the cover of smoke, men began manoeuvring around the German lines, but once again the wind shifted and exposed the Nisei soldiers to enemy fire. Major Lovell, the unit XO, was wounded and left writhing on the ground near Sergeant Gary Hisaoka. Sgt. Hisaoka, determined to rescue his XO, began digging a shallow trench toward the wounded Lovell. After getting 8 yards, Hisaoka got impatient, tossed down his shovel and dashed the remaining 8 to 10 yards to Lovell. There he grabbed the XO’s arms and dragged him back to safety.

Elsewhere on the line a German assault gun rolled in to attack the hapless Americans. Private Masao “Tankbuster” Awakuni came to the rescue. Rushing forward, Awakuni dodged enemy fire to reach a position 30 yards from the German tank. Here he fired his bazooka, but only struck the vehicle’s track. Gritting his teeth, he reloaded and exposed himself to enemy fire to try again. The shell struck the tank’s hull solidly, but nothing happened. A dud. Reloading once more, Tankbuster Awakuni braved the German guns and fired; his round flew true and destroyed the tank. German machine gunners concentrated fire on his position, wounding his arm and forcing him to hide behind a boulder until nightfall. For his valiant assault, Awakuni was awarded a DSC.

Elsewhere on the line a German assault gun rolled in to attack the hapless Americans. Private Masao “Tankbuster” Awakuni came to the rescue. Rushing forward, Awakuni dodged enemy fire to reach a position 30 yards from the German tank. Here he fired his bazooka, but only struck the vehicle’s track. Gritting his teeth, he reloaded and exposed himself to enemy fire to try again. The shell struck the tank’s hull solidly, but nothing happened. A dud. Reloading once more, Tankbuster Awakuni braved the German guns and fired; his round flew true and destroyed the tank. German machine gunners concentrated fire on his position, wounding his arm and forcing him to hide behind a boulder until nightfall. For his valiant assault, Awakuni was awarded a DSC.

Over the following days, the American forces dug in, unable to gain ground, and eventually most of the 100th was put in reserve. Company B was sent forward to support 3rd Battalion, who were fighting in the town. Here, the AJA soldiers held an ancient church against German assaults and shelling for four days and nights. Much of the urban combat involved grenades, and as such a curious news correspondent who had braved the front asked the weary soldiers about their throwing technique. The reply was simple: “Mister, all you gotta do is throw straight and throw first. That’s the number one thing, throw first.”

On March 10, the remains of the 100th Infantry were sent to Sant Giorgio to rest and reorganize. Here they received 161 rookie soldiers from the 442nd’s 1st Battalion to replace combat losses. On entering Italy, the 100th had 1,300 men. After Monte Majo on the Winter Line, they were left with 832. After Cassino that number shrank to 521, less than half their original strength. The fighting at Cassino left 48 killed, 144 wounded, and a further 75 succumbed to various illnesses.

During this rest period, the 133rd’s 2nd Battalion was returned to the fight, but General Ryder kept the 100th as a Separate Battalion within his Division. After two short weeks of rest and training the rookies, 34 Division boarded LSTs bound for the Allied beachhead at Anzio. It appeared that the brave Japanese-Americans were to face yet another stubbornly unbreakable German line. Command of the unit changed once again on April 2nd, with Colonel Gordon Singles being made CO, and a few days later another 280 reinforcements arrived from the 442nd. The next two months passed uneventfully, with neither the Allies or the Germans making any significant headway.

The only notable event in that period was Captain Young Kim’s daring recon patrol of May 16. Capt. Kim and PFC. Irving Akahoshi volunteered to capture a couple German soldiers to get current intelligence for Allied command. They took three volunteers with them and departed HQ just before midnight. Creeping through waist high drainage ditches, the men slipped past the German front lines until about 2AM when they heard the sounds of digging. Capt. Kim opted to wait for daybreak, then advanced on his belly with Akahoshi through a field of grain. Two hours and 250 yards later they heard German conversation and the sound of weapons being cleaned. Inching forward, Kim found two Germans resting in a slit trench. He ordered their surrender at the point of his Thompson, and with his cohort led the two Germans back to allied lines, narrowly avoiding detection. They safely returned to their HQ around 4 PM and were awarded DSCs for their daring raid.

June 2nd marked the start of the last major action that the 100th took part in as a Separate Battalion. During the breakout from Anzio, the 100th was attached to the 135th RCT in place of their 1st Battalion. Here, they advanced under heavy mortar fire on the hamlet of Pian Marano, just west of Lanuvio. They contacted the enemy around 0900 and fought continuously until the next morning when the hamlet was captured. During the fighting, PFC Hiroshi Yasotake of Company C distinguished himself. Capturing an abandoned German gun emplacement, he fired down on flanking German soldiers, defeating their advance, and then engaged in a 10-minute duel with a machine gun nest over 700 feet away, eventually silencing the German gunners with his BAR. His gallantry earned him a DSC.

After Pian Marano was captured, Colonel Singles was given command of a taskforce that augmented the 100th Infantry with the 125th and 151st Field Artillery Battalions, Company C of the 191st Tank Destroyer Battalion, Company A of the 804th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and Company C of the 84th Chemical Mortar Battalion. Using these forces, the 100th was to mop up the heavily entrenched 29th Panzer Group on Hill 435, at Lanuvio. Battle commenced at 2030 with Company A climbing the hill under cover of fire from the 125th Field Artillery. However, they soon became pinned down by machine gun and mortar fire, prompting Company B to flank left and C to flank right. The ‘Task Force Singles’ tank destroyers saturated the crest of the hill with remarkably accurate fire, wiping out enemy gun emplacements, while the 84th Chemical Mortars provided smoke cover. By midnight the hill was captured and the 29th Panzer Group routed, Company C having captured over 50 prisoners. Other Allied elements were shocked at how quickly the taskforce beat the Germans and mistook the 100th for German soldiers as they broke through the German salient. Allied artillery, reacting to the perceived threat, fired on the 100th, wounding and killing some before a ceasefire was ordered. The action at Lanuvio earned the 100th more casualties, but also more heroes with 6 DSCs awarded, 1 Silver Star, and 3 Bronze Stars.

With the last resistance between Anzio and Rome cleared, Task Force Singles sped down the road and by 1500 on June 5th reached a road sign proclaiming the capital to be only 10 kilometres away. Here, the task force was ordered to halt and await transportation. To the disgust of the Nisei soldiers, they were forced to watch from the side of the highway was other American units sped on to liberate Rome. Finally, after 2230 on June 5th, the men of the 100th Battalion began to filter into Rome, two years to the day after they had left Hawaii. The next day the unit moved to Civitavecchia, then to a valley seven miles north on the 10th. Elements of the 442nd RCT began to arrive in the valley on the 11th, and on June 17th the 100th Infantry Battalion was officially merged with the 442nd, replacing 1st Battalion. Here, the units drilled together, with the veterans passing on their knowledge much as the 34 Division men had done in Oran. Together, the 100th Battalion/442 Regimental Combat Team would continue fighting hard, determined to win at all costs and never turn back.

Conclusion

By the end of the war, around 18,000 Nisei served in the 100th Infantry Battalion or the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and the units suffered an astounding 314% combat casualty rate, partly due to their tenacious fighting spirit and refusal to give up. The soldiers of the 100th Infantry Battalion fought like men possessed, working at every step of the way to prove their loyalty to the United States above all. Despite this heroism and tenacity, they were all but forgotten by their contemporaries. Their crucial role in smashing the German lines at Lanuvio isn’t even mentioned in the US Army’s official history of the campaign.

The 100th Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team were the most decorated unit in US Army History, for their size and length of service. These men were widely recognized for fighting with incredible bravery, motivated by loyalty to friends and family, and a deep commitment to their country. Many of them fought valiantly, even though their families back in the US lived behind barbwire in internment camps, far from their homes. Despite all this, only one Japanese soldier received the Medal of Honor for his sacrifice above and beyond: Sadao Munemori, A Company, 100th Infantry Battalion. Over fifty years later, the United States Congress ordered the Army to review the records of Japanese recipients of the DSC during World War II. As a result, on June 21, 2000, President Clinton presented 7 Medals of Honor to living veterans, and a further 13 posthumous awards. Six were original members of the 100th Infantry Battalion, 3 of whom were killed during the assault on La Croce Hill. Among the other individual awards granted members of the 100th/442nd were 29 Distinguished Service Crosses, 560 Silver Stars, 28 Silver Stars with Oak Leaf Cluster, 4,000 Bronze Stars, 1,200 Bronze Stars with Oak Leaf Cluster and a staggering 9,486 Purple Hearts.

by Robert Morrison

Bibliography

Print Sources:

Asahina, Robert. Just Americans: How Japanese Americans Won a War at Home and Abroad: The Story of the 100th Battalion/442d Regimental Combat Team in World War II. Gotham Books, 2007.

Crost, Lyn. Honor by Fire: Japanese Americans at War in Europe and the Pacific. Presidio, 1996.

Duus, Masayo. Unlikely Liberators: The Men of the 100th and 442nd. University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

Masuda, Minoru. Letters from the 442nd the World War II Correspondence of a Japanese American Medic. Edited by Hana Masuda and Dianne Bridgman, University of Washington Press, 2011.

Murphy, Thomas Daniel. Ambassadors in Arms; the Story of Hawaii’s 100th Battalion. University of Hawaii Press, 1955.

Online Sources:

100th Infantry Battalion Veterans Education Center, 100th Infantry Battalion Veterans, www.100thbattalion.org/

Go For Broke National Education Center – Preserving the Legacy of the Japanese American Veterans of World War II, Go For Broke National Education Center, www.goforbroke.org/.

Japanese American Veterans Association – Nisei Legacy, Japanese American Veterans Association, java.wildapricot.org/.

The Nisei in Bolt Action

In a future article, we’ll be bringing you new theatre selectors and rules for fielding the legendary 100th Battalion in-game, along with notable characters and even a couple of brand new scenarios to try out. The Nisei – 442nd Regimental Combat Team is now available for Pre-Order in our webstore. Replicate the daring actions of this most decorated fighting force in the Italian Campaigns on the tabletop.