Today we’re heading back to 1798 to the Battle of the Nile, where Nelson scored a famous victory that secured the Royal Navy’s dominance on the seas.

Also known as the Battle of the Aboukir Bay, the Battle of the Nile marked a turning point in strategic naval dominance for the British in the war. Fought on 1st August 1798, the battle is particularly famous for the spectacular destruction of the French flagship, the Orient, in a fiery explosion that briefly turned night into day.

Prelude to Battle

The battle was the culmination of a long hunt by Nelson to locate the French fleet. It was apparent that Napoleon intended to invade somewhere in the Mediterranean, it was just a question of where. In May 1798, Nelson arrived at Gibraltar and was tasked with discovering the French movements. All was not smooth sailing, as Nelson’s exploratory fleet was beset by poor weather, and Nelson’s flagship, HMS Vanguard, suffered heavy damage, though this was repaired extraordinarily quickly. During this misfortune, however, the French fleet departed Toulon, leaving the British oblivious to their specific destination.

It was supposed that Napoleon’s objective would be an invasion of Egypt. This caused a stir in parliament and within the East India Trading Company. Nelson’s fleet was thus substantially reinforced, bringing the fleet up to 13 ships of the line, though he lacked any frigates. These had failed to return after the initial fleet had dispersed during the storm. Pushed for time, Nelson was forced to set sail without them.

Much of the information that the British gleaned came from passing merchant’s vessels. Nelson thus learnt that Malta had been taken but Napoleon had opted to sail east on June 16th. Nelson set sail for Eqypt but failed to locate any sign of the French fleet. The French fleet, in fact, arrived the next day, having been sailing more slowly than Nelson’s fleet in its race to intercept. Nelson turned northwards and then back towards Sicily. With no sign of the French fleet and all indications that Napoleon had gone eastwards, Nelson set out to Eqypt once again, reaching Alexandria on 1st August. This time, rather than finding the port empty, he found it full of French transport vessels. The signal was raised at around 6 pm, ‘Enemy in Sight’.

The Two Fleets

Ships’ crews of all nations were tough. The British were particularly well-drilled, having been in continual service blockading both the Spanish and the French. With this efficiency, Royal Navy crews could fire three broadsides for every two fired by the French crews. This is because the French were still recovering from the losses of superior naval personnel, culled by execution or exilement as a result of the French Revolution of 1789.

At Aboukir Bay, Admiral Brueys was unprepared for battle. The fleet had been incapable of anchoring within the port of Alexandria, due to the overwhelming number of French transport vessels. They had therefore been forced to relocate east of Alexandra to the bay. The French ships were ill-supplied and ill-manned following their journey from Toulon. A significant portion of the crews was ashore, digging wells to resupply the fleet. The Admiral had arrayed his ships in a line with his flagship, Orient, in the centre, as close to the shore as possible to prevent the British, should they appear, from attacking from landwards.

His mistake was in leaving too much of a gap between his ships. Gaps that the British could exploit to expose the vulnerable sides of the French vessels. In a classic example of British gunnery doctrine, the British ships held their fire until right alongside the French ships – to ensure maximum effect. They advanced under the fire of the French Fleet and the shore batteries on Aboukir Island, their own guns silent, like phantoms drawn out from the encroaching night.

Royal Navy

‘If I were to die today you will find engraved on my heart ‘lack of frigates.’

– Horatio Nelson

The British fleet was composed of 13 ships-of-the-line (as well as HMS Culloden – which took no part in the battle and HMS Mutine, an 18 gun-brig) and a 50-gun Gunship, for a total of 1012 guns, under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson.

| Ship: | Captain: | Place in Line: |

| HMS Goliath (74 guns) | Captain Thomas Foley | 1 |

| HMS Zealous (74 guns) | Captain Samuel Hood | 2 |

| HMS Theseus (74 guns) | Captain Ralph Miller | 3 |

| HMS Mutine (18 guns) | Lieutenant Thomas Hardy | 4 |

| HMS Orion (74 guns) | Captain Sir James Saumarez | 5 |

| HMS Vanguard (74 guns, Flagship: Rear-Admiral Nelson) | Captain Edward Berry | 6 |

| HMS Minotaur (74 guns) | Captain Thomas Louis | 7 |

| HMS Defence | Captain John Peyton | 8 |

| HMS Bellerophon | Captain Henry Darby | 9 |

| HMS Majestic | Captain George Blagdon Westcott | 10 |

| HMS Leander | Captain Thomas Thompson | 11 |

| HMS Audacious | Captain Davidge Gould | 12 |

| HMS Alexander | Captain Alexander Ball | 13 |

| HMS Swiftsure | Captain Benjamin Hallowell | 14 |

| HMS Culloden | Fleet Captain Thomas Troubridge | 15 |

French Navy

The French fleet was composed of 13 ships-of-the-line and 4 frigates, totalling 1196 guns under the command of Vice-amiral François-Paul Brueys D’Aigalliers.

Seaward

| Ship: | Captain: | Place in Line: |

| Guerrier (74 guns) | Captain Jean-François-Timothée Trullet (senior) | 1 |

| Conquérant (74 guns) | Captain Etienne Dalbarade | 2 |

| Spartiate (74 guns) | Captain Maurice-Julien Emerriau | 3 |

| Aquilon (74 guns) | Captain Antoine René Thévenard | 4 |

| Peuple Souverian (74 guns) | Captain Pierre-Paul Raccord | 5 |

| Franklin (84 guns,Flagship: Vice-amiral Armand Blanquet du Chayla) | Captain Maurice Gillet | 6 |

| Orient (118 guns, Flagship: Vice-amiral François-Paul Brueys D’Aigalliers, Fleet Captain Honoré Ganteaume on board) | Captain – Commodore Luc-Julien-Joseph Casabianca | 7 |

| Tonnant (80 guns) | Captain – Commodore Aristide Aubert Du Petit Thouars | 8 |

| Heureux (74 guns) | Captain Jean-Pierre Etienne | 9 |

| Mercure (74 guns) | Captain Cambon | 10 |

| Guillame Tell (80 guns, Flagship: Rear-Amiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve) | Captain Saulnier | 11 |

| Généreux (74 guns) | Captain Claude-Jean Martin | 12 |

| Timoléon (74 guns) | Captain Louis-Léonce Trullet (junior) | 13 |

Landward

| Ship: | Captain: | Place in Line: |

| Sérieuse (32 guns) | Captain Claude-Jean Martin | 14 |

| Artémise (32 guns) | Captain Pierre-Jean Standelet | 15 |

| Diane (38 guns) | Captain E. J. N. Solen | 16 |

| Justice (40 guns) | Captain Villeneuve | 17 |

Battle is Joined

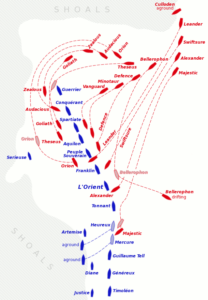

At 18.20 the French fleet opened fire on the lead ships of the British Vanguard. Upon his approach, Captain Thomas Foley of HMS Goliath, noticed a gap between the lead French ship, Guerrier, and the shallows of the shoal. Under his own initiative, Foley changed his angle of attack to exploit this. The double-shotted raking broadside against the unprepared port side of Guerrier was devastating.

The speed of the British attack took the French Captains by somewhat of a surprise, who were still aboard the Orient in conference when the firing began. They scrambled their boats to return to their own ships.

Orion was the third British ship into the French line and was fired upon by the frigate Serieuse. The convention of naval warfare at the time was that ships-of-the-line did not fire on frigates unless attacked first, but the French captain had not paid heed to this. The Orion reduced the frigate to a wreck with a single broadside.

The following ships in the British line angled to the starboard at the French, The plan was that each French ship would engage two British ships at a time and the giant Orient would have to contend with three!

Of note was the final ship of the British line, HMS Culloden, which ran aground when sailing too close to the shoal in the gathering darkness. Its hull suffered heavy damage and it took no part in the battle. HMS Mutine, the 18-gun Brig – which itself took no direct part in the battle – attempted to assist the stricken vessel.

For three hours the French Vanguard was pummeled from both sides, heavily outnumbered by the British fleet. The centre of the French line remained resolute. Orient traded fire with Bellepheron – both ships suffered incredibly, with Brueys being struck by a cannonball and Bellepheron forced to withdraw from battle.

For three hours the French Vanguard was pummeled from both sides, heavily outnumbered by the British fleet. The centre of the French line remained resolute. Orient traded fire with Bellepheron – both ships suffered incredibly, with Brueys being struck by a cannonball and Bellepheron forced to withdraw from battle.

With the French vanguard in tatters and the Royal Navy reinforced by the late arrival of HMS Swiftsure and HMS Alexander, the battle of at the centre of the French line swayed once again as the Orient was beset by an onslaught of fire from all quarters.

Destruction of Orient

Orient, at the heart of the French fleet, though putting up a fierce fight, had suffered heavy damage. A fire broke out on deck around 9pm. The ship was effectively immobilised whilst crews fought to quell the flames. The British did not let them.

Spotting the danger to the French flagship, the British concentrated their firepower on the stricken ship. The crew was unable to extinguish the rapidly spreading fire, and at around 10pm it reached the on-board magazines.

The resultant explosion was legendary.

The destruction of the Orient is one of the defining images of naval warfare, inspiring a wealth of artistry. The explosion was said to briefly spell the night’s end and was heard miles inland by French troops. Hostilities ceased for several minutes as crews recovered from the shock of the unexpected ferocity of the explosion. Flaming wreckage posed a danger to ships of both fleets, and resultant fires were extinguished on nearby ships.

Only one French ship remained engaged by midnight, the Tonnant. In the early hours of 2nd August, though continuing to trade fire with the French, Nelson’s fleet was largely able to consolidate their prizes and improvise repairs. By sunrise, the Tonnant had drifted south to join the French rear division, which had remained an ineffectual (and bearly involved) component of the greater battle. It was thus that this division, under the command of Amiral Villeneuve on board the Guillaume Tell, found itself a target. Only four French ships managed to escape the battle. In addition to his flagship, the 3rd rate Genereux and the frigates Justice and Diane struck their lines and fled for the mouth of the river.

The morning of 3rd August saw Nelson move to force a surrender from the remaining French ships. The eleventh, and final, French ship-of-the-line to meet a demise was the Timoleon, set alight by its own crew, which opted to escape to the shore rather than surrender.

Aftermath

British casualties numbered 895. This included the death of Captain Westcott. Nelson, although wounded, refused to include himself in the official return. French casualties meanwhile, were catastrophic. 5225 were dead with an additional 3105 captured. The French Admiral, Brueys, had died on the Orient prior to its spectacular destruction.

The British victory was so complete that it effectively spelt an end to Napoleon’s Egypt campaign; meaning that British control of India remained secure. Napoleon returned to France, abandoning his army to its fate. Nelson, for his part, was decorated for his actions earning the title of Baron. In addition to cementing British naval dominance, the battle secured Nelson his reputation as an extremely capable naval commander.

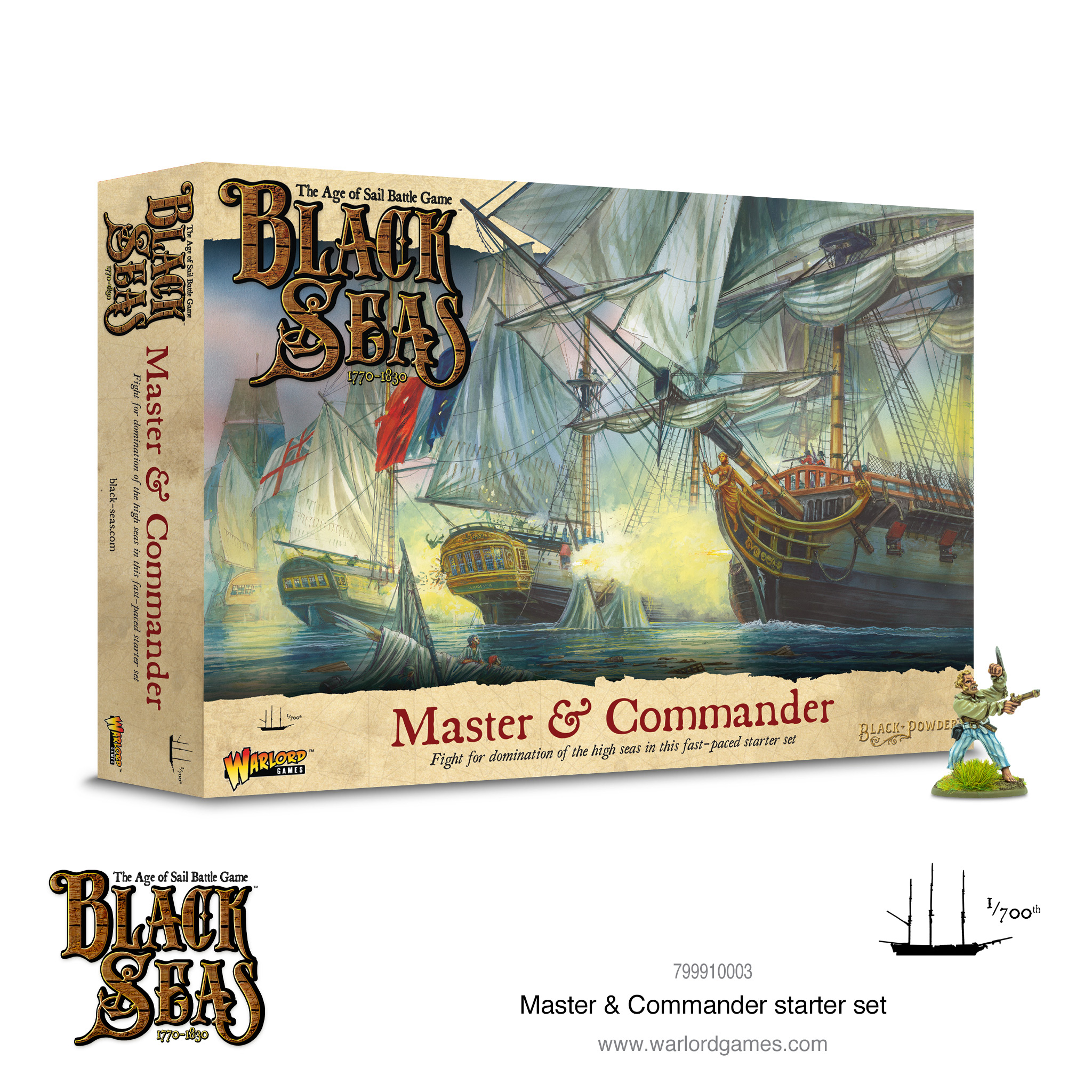

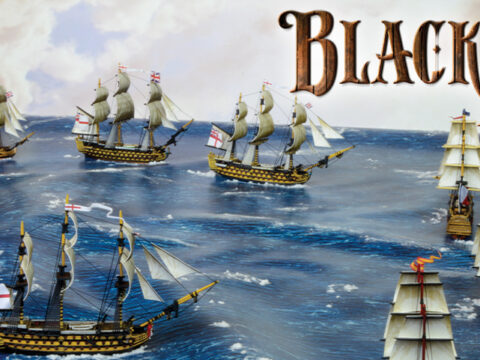

Black Seas

Command your own fleets to victory The ideal starting point is the Master & Commander starter set, netting you 6 brigs and 3 frigates, as well as the full rules and everything needed to play. Then expand your navy with the British and French fleet boxed sets!

To re-enact the Battle of the Nile, you’ll need the most famed ship at the conflict, L’Orient!