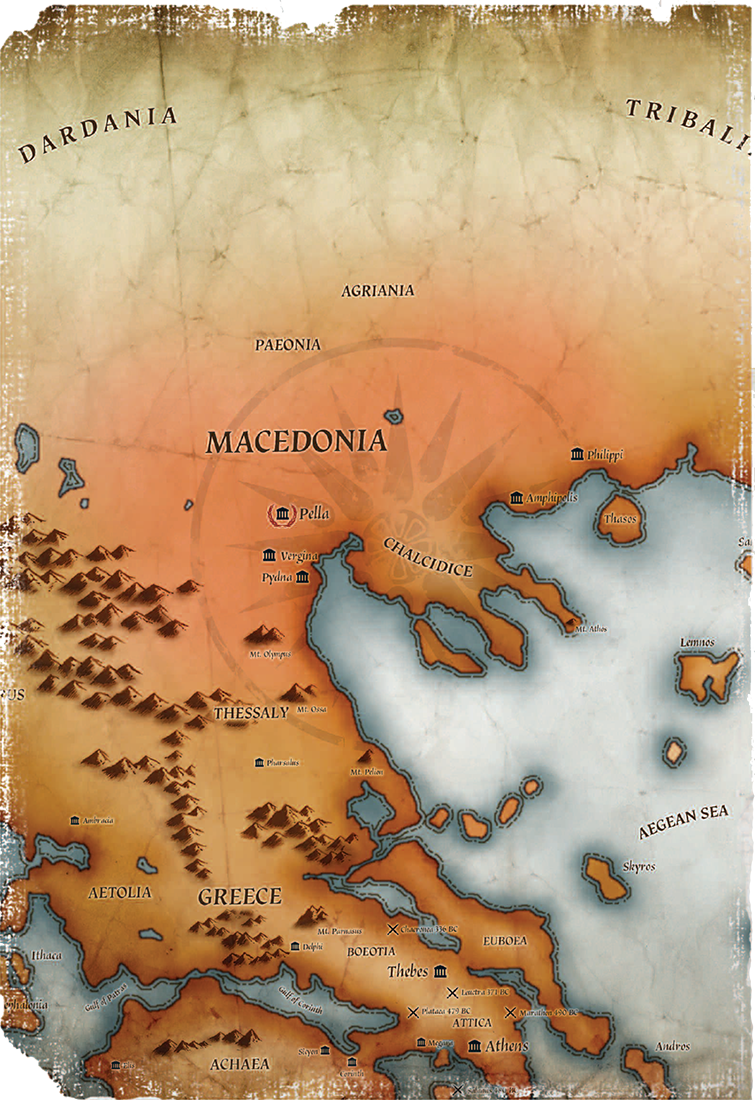

The Kingdom of Macedonia created an empire that spanned much of the known world, its armies defeated those of every nation it met. Building upon the civilisation of the Greek city-states(which the Macedonian armies crushed) this empire spread Western culture, philosophies and science a vast distance, forming the roots of our society today. When people speak of a Greek empire, it is the Macedonians they are talking about, spearheaded by warbands that contained disciplined men using innovative tactics, controlling land from Egypt to the fringes of India.

A New Macedonia

Greece had been dominated by its most powerful city-states, principally Athens and Sparta (though Thebes was always present to make things more exciting). While not true empires in any sense, these city-states were organised and strong enough to resist even massive Persian invasions.

Macedonia, to the north, was a shadow of this civilisation and it was not until King Philip II rose to power in 359 BC that this began to change. As the Macedonian army swelled in size, Philip II instituted new tactics and training that formed the basis of a brand new army, the likes of which the ancient world had not yet seen. It is possible he started forming these ideas while kept as a hostage in Thebes, taking their Sacred Band as a model of what soldiers could be when suitably trained and motivated.

The traditional Greek phalanx was deepened in ranks and each was given its own ranking commander. This, combined with the introduction of standards, allowed for much greater control on the battlefield. The most obvious addition visually was the appearance of the sarissa, a pike with much greater length and reach than the spears of the Greeks.

Borrowing an idea from the Spartans, Macedonia would also stop using citizen-soldiers and instead have a standing professional army. As the empire expanded, the wealth and people from dominated cities aided this, passing menial work to a growing slave population and freeing fighting men for the army.

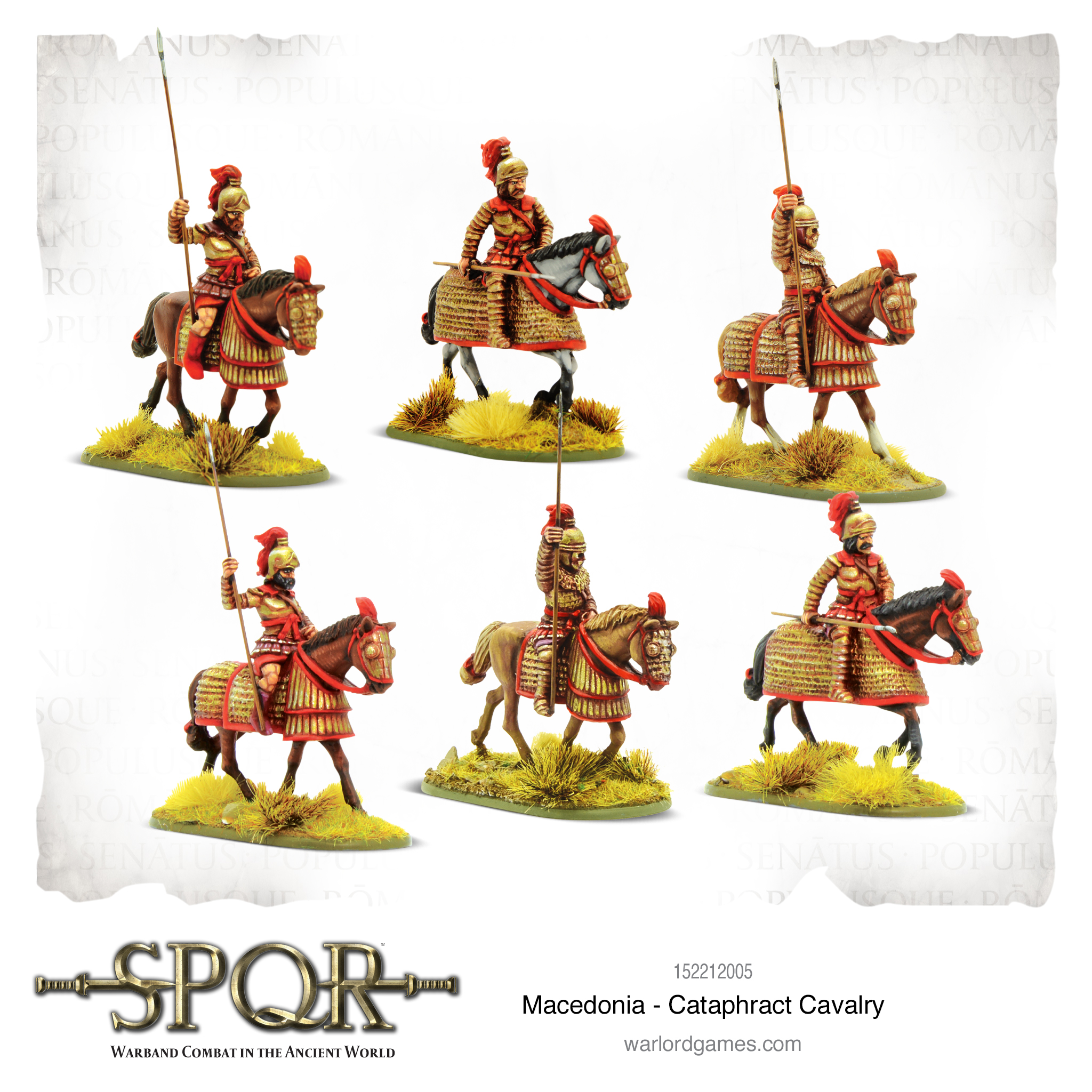

The phalanxes themselves would change their focus on the battlefield too. Instead of forming the core of the army’s hitting power, their role was to engage the enemy and hold them in place. Macedonia’s new heavy shock cavalry would then smash their formations apart, leading to quick, decisive victories.

Appearance & Equipment

Perhaps predictably, there is very little conclusive evidence for uniforms within Macedonian forces and as the empire grew beyond the bounds of Macedonia and Greece, the inclusion of soldiers from further afield only makes things less clear. At the end of the day, all there is are sporadic samples of art, a few remains, and cryptic comments by historians, along with a smattering of stray references elsewhere.

However, some conventions have gained acceptance among historians and miniatures gamers, though always with the caveat that these conventions may simply be wrong. There is some debate as to whether Macedonian soldiers and cavalrymen painted their helmets to distinguish themselves on the battlefield.

There is some evidence that this was indeed done in the ancient world and the colour blue if often cited as a ‘Macedonian colour.’ As is usually the case, it is difficult to determine whether this was unusual, whether it was adopted by a certain type of troop, or whether it was adopted on an army-wide scale.

It is probably safe to say that at least some Macedonian soldiers wore blue – make of that what you will! The colour purple is sometimes raised as a possibility for the cloaks and/or tunics of the Companion cavalry, though there is also a counter-argument that purple was reserved for royalty and would have been beyond the means of even the Companions.

Beyond that, there are also suggestions that Macedonian troops may have had a wide range of colours that would seem very garish today, especially after their victory over the Persian Empire when the army was a great deal richer. Light blues, reds, and even pinks may well have been common.

Shields may well have had an eight-pointed star though there are some that advocate quite elaborate facings. Common sense would suggest that the majority of soldiers would have sported the simpler star design if large numbers of them were expected to use those shields to stop incoming blows. However, it is conceivable that leaders and maybe some elite troops would have had more complicated designs.

As with many eras in the ancient world, the choice of colours and uniforms often comes down to the choices made by the player and what he or she is comfortable with. It is also useful, in games, to have units easily marked out so soldiers from one do not get mixed up with others – thus, it is a very easy step to have the linothorax armour as off-white across the entire army with units picked out by different coloured tunics. This is an easy policy to follow, will help identify miniatures during games and has the advantage that it is as historically justified as any other scheme.

Always remember that miniatures gamers may be far more concerned about the look of their troops than real-world generals were in the ancient world!

The Macedonian Warband

The rise of true combined arms forces started with the Macedonians, with armies using phalanxes not to necessarily win battles but hold enemies in place long enough for Alexander’s favoured cavalry to break them apart. There were even the beginnings of special forces units, the Hypaspists. On the open battlefield, these elite soldiers were used to guard the flanks of phalanxes that would otherwise be vulnerable, but they were fully capable of engaging in ‘special’ missions that might include night-time raids or strikes against specific objectives.

A Macedonian warband will comprise solid phalanxes of troops that are very difficult for even elite enemy units to shift, alongside powerful heavy cavalry capable of smashing them apart with ease.