Tomorrow marks the anniversary of the Battle of Blenheim, arguably the most famous of battles of the War of the Spanish Succession, fought on 13th August 1704.

An Unassailable Position

French Marshall Tallard was moving to attack Vienna, hoping to knock Austria out of the war if it succeeded. The Duke of Marlborough managed to march Anglo-Dutch army from the Channel to the Danube in little over a month, considered quite a feat for eighteenth-century armies. Furthermore, he achieved this without giving away his ultimate goal, and joined forces with Prince Eugene of Savoy’s Imperialist forces before moving to attack the Franco-Bavarians.

Marshal Tallard’s force numbered some 56,000 men, and he considered his position unassailable – with his right flank protected by the Danube and his left by heavy woodland. The centre was occupied by the villages of Oberglau and Blindheim (Blenheim to the British) which had been heavily fortified and defended. Furthermore, the French front was protected by a tributary of the Danube around which sprang difficult to traverse marshlands. Nevertheless, Tallard’s army found itself attacked, quite to his surprise.

Battle is Joined

The 20,000 Imperialists under Prince Eugene concentrated their attack against the 30,000 French and Bavarians on their left but failed to make much headway against the well-disciplined defenders. The British meanwhile attacked Blenheim. Although their initial efforts were turned away, the French commander was so concerned that the French reserves were moved in to shore up the town’s defences, thus diverting manpower that was badly needed elsewhere. The result of this was that a staggering twenty-six battalions were concentrated in the defence of a relatively small area.

The Dutch, for their part, concentrated their attack on the second village, Oberglau, but were also repelled. Marlborough, however, with defenders diverted, was able to cross the tributary in the centre, successfully bringing a battery of cannons across the difficult marshy grounds. Supported by renewed attacks from the Dutch, he was able to hem in the remaining defenders in Oberglau. The remainder of his forces drove at the French centre, and despite desperate cavalry counterattacks could not be held back. This enabled Marlborough to swing against the Bavarians, who, now facing pressure from both the centre and renewed attacks from the Imperialists, were forced to retreat.

Whilst the rest of the French routed, those Frenchmen left in Blenheim found themselves surrounded with no recourse other than to surrender. The result would prove to be the greatest of all victories achieved against one of Louis’ armies. In its time, it would prove to be as significant a battle as that of Waterloo over a century later.

Refighting the battle using Black Powder

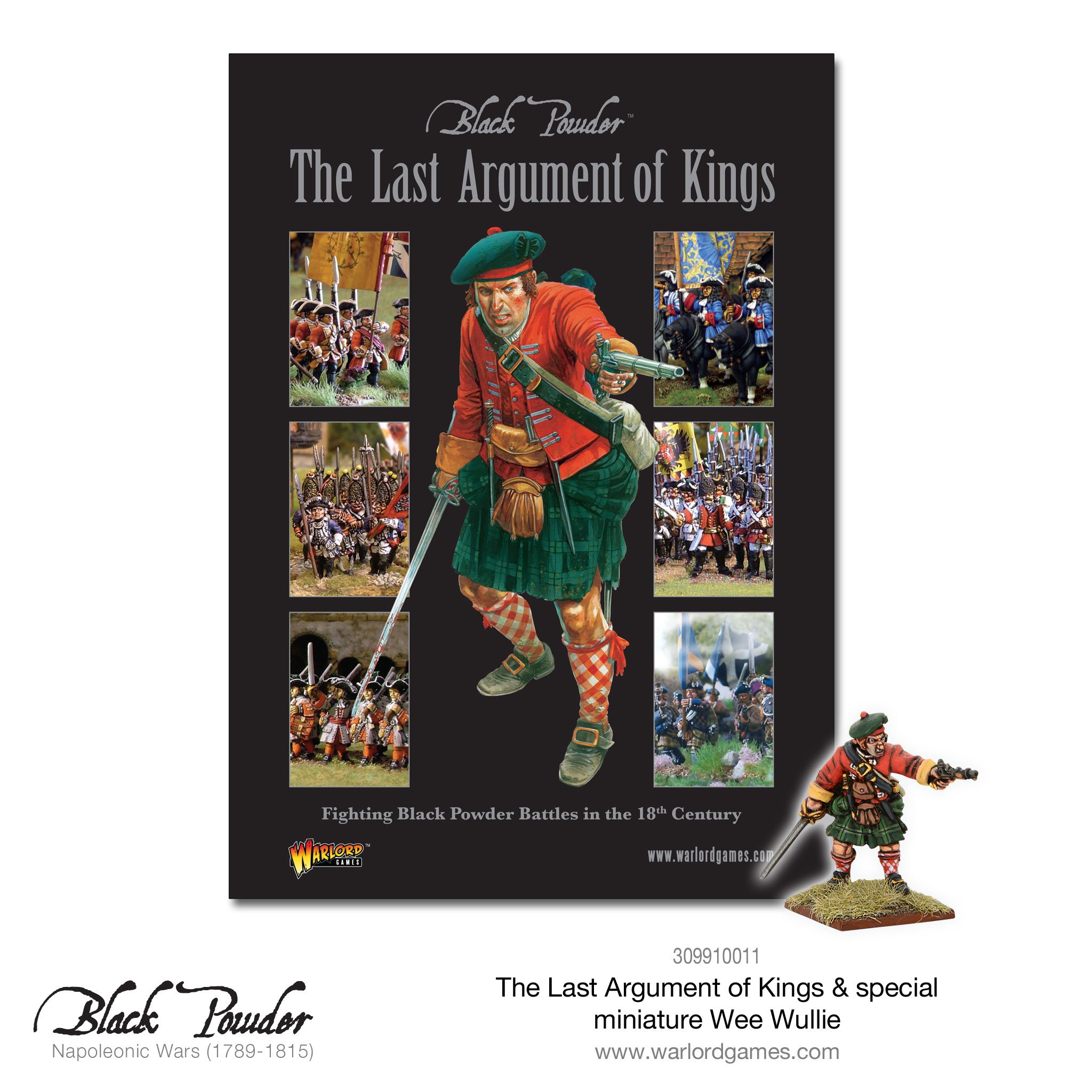

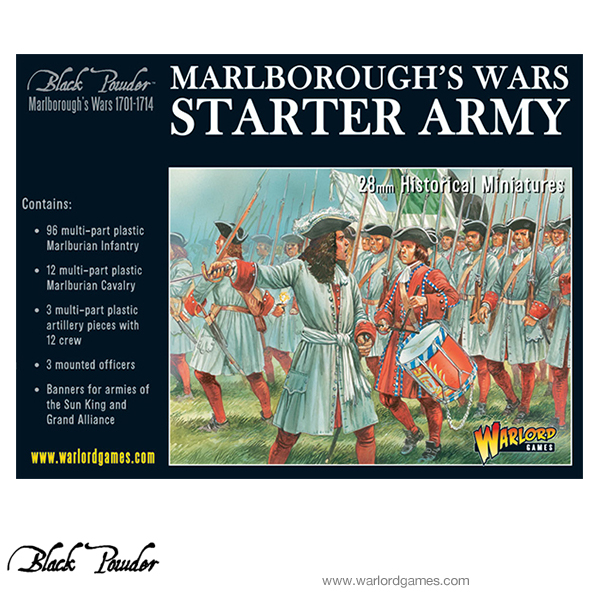

The Battle of Blenheim poses a particular problem for wargamers aiming to refight it – that of scale. The battle involved some 100,000 men fighting over a front that spanned four miles. Nevertheless, the Black Powder Supplement, Last Argument of Kings, provides guidance for replicating specific areas of the battle, and gives players the option to incorporate special rules to reflect the conflict. For instance, Marlborough’s Artillery commander, Colonel Holcroft Blood, showed particular diligence in manoeuvring his artillery across the Nebel (the tributary of the Danube). To reflect this, if players wish, gun models or batteries in base contact with Colonel Blood can always move, regardless of command rolls for the brigade or brigade commander. The book also details all the special rules for wielding the armies of the Spanish Succession on the tabletop.

Marlborough at Blenheim

When the battle of Blenheim was over, the Duke of Marlborough, whilst still in the saddle and surrounded by his victorious troops, took a moment to write a short note to his wife, Sarah, to tell her of the victory. The note, rather famously, was written on the back of a tavern bill and the Duke leaned on a drum to steady his hand. The note read:

“August 13, 1704. I have not time to say more, but to beg you will give my duty to the Queen and let her know her army has had a glorious victory. Monsieur Talland and two other Generals are in my coach and I am following the rest: the bearer, my aide-de-camp, Colonel Parke, will give her an account of what has passed. I shall do it in a day or two, by another more at large. Marlborough.”

We have based this command group vignette on Hillingfords famous oil painting of this event. In it, a page steadies the Duke’s horse whilst an aide de camp holds up a drum for the Duke to lean on whilst he writes his note. In the foreground, a soldier collects the standards of the fleeing French regiments to present to the victorious Duke.