After disbanding parliament and unsuccessfully try to force a unified book of common prayer upon Scotland, King Charles I was left in a very weak position.

He had to recall Parliament (the Long Parliament) at the end of 1640 and it was clear to MPs that they had leverage over the king. They used this power to put Archbishop Laud and Thomas Wentworth on trial for their lives and had them executed. Charles also agreed that he could no longer disband parliament without their consent.

Where he drew the line was with the creation of the ‘Grand Remonstrance’ in which Parliament had laid out both the positives of his reign, but also his failings. This was an insult too far, and he made the rash move of marching to the House of Commons with an armed escort to arrest Pym and other senior politicians. However, Pym and his colleagues had fled after being tipped off, and the king raged impotently.

When parliament demanded that the country’s military should fall under their control and not the king’s, Charles realised that London was no longer a safe place for himself and his family. He marched north to raise the Royal Standard in Nottingham in August 1642, and so the Civil Wars began.

The First English Civil War 1642-1647

As soon as the Royal Standard was raised in Nottingham on that fateful summer day in 1642 there was a rush to gain recruits for the cause. The king could call on much of the north and west of England, while Parliament recruited broadly from the south and east; however the real picture was far more confused than that. Local landowners were wooed by both sides to raise regiments (many Members of Parliament were also to raise regiments of their own), and these landowners could tip the balance of power in the shires.

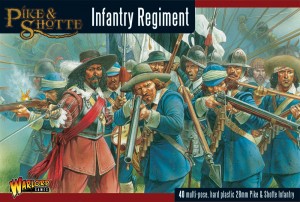

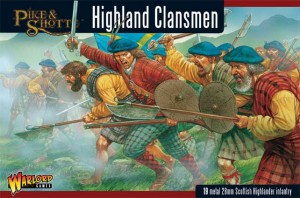

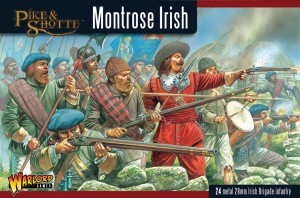

Troops were also recruited from Scotland, Ireland and from those soldiers who had been fighting on the continent in the Thirty Years War. Local ‘Trained Bands’ were also dragged en masse into the fray; although it is the London Trained Bands that have received most of the popular attention, such forces were to be found throughout the country. With such a diverse supply of soldiery it is understandable that the quality of the troops varied considerably, as did the quality of command as many of the noblemen raising regiments were just enthusiastic amateurs.

Parliament was marginally more prepared for war, and commanded London and the main trade ports such as Bristol, Plymouth and Hull. The Navy had also come out in support of parliament, which allowed their armies to be better supplied. A counter to this was the fact that many parliamentarians were wary of committing to a total war, as defeat would mean execution for treason.

The Midlands was to be “where England’s sorrows began” with parliament forces under the Earl of Essex sparring with Prince Rupert’s royalists. On the 23rd September 1642 the cavalry of both armies stumbled across each other at Powick Bridge, just outside Worcester. In the ensuing skirmish Rupert led his men to victory from the front, gaining the reputation of a dashing and brilliant leader. Although only a skirmish, in real terms the psychological effect was immense and the spectre of Rupert’s unbeatable cavalry was to haunt the parliament forces.

A month later the first major battle of the war took place at Edgehill in Warwickshire. This battle was inconclusive, with many troops on both sides proving unreliable and neither side gaining any particular advantage. The road to London had been left open for Charles to make an advance on the capital. However when he finally made his move he was forced to turn back at Turnham Green when confronted by a much larger parliamentary force.

This was the closest Charles made it back to London, until he was taken there as a prisoner years later. With London closed to him, the Royalist cause set up a new capital in Oxford and both sides settled in for a long winter, knowing that this certainly would not be over before Christmas.

The War Drags On

The year 1643 began so well for the Royalist cause, and the campaign season seemed to have turned the tide of the war inexorably in their favour. In fact by August of that year a whole series of Royalist victories had led to the term ‘Royalist Summer’ being used.

Bristol had been laid siege to and captured by forces under Prince Rupert, and victories in the south west for Lord Hopton had secured that region. Even up north things were looking a little less grim, with the defeat of Lord Fairfax’s parliament army at Adwalton Moor.

These victories were not enough to gain complete dominance, and parliament started to fight back. Gloucester successfully held out against repeated Royalist efforts to capture it, with great loss of life. Another major though inconclusive battle was fought, this time at Newbury. (This venue was to prove popular so today this battle is known as First Newbury.)

As another year dragged to a close, the end of the war was no nearer to hand, and so both camps withdrew into winter quarters once more. By this time parliament had no fewer than five armies to feed and equip; those of the Earl of Essex, the Earl of Manchester, Sir William Waller, Lord Fairfax and the Earl of Denbigh. Not only were there political intrigues in place between these characters, but their ability (and willingness) to pursue the war were beginning to be questioned.

The Tide Turns

The year 1644 saw the Scots Covenanter forces stepping in to aid parliament; this could only mean trouble for the king. A large force of Scots moved south to help with the siege of York and so Charles sent Rupert north to combat the threat.

Rupert did manage to raise the siege of York, but the following day (July 2nd) his army was smashed by the combined forces of the northern parliamentarians and Scots Covenanters at the Battle of Marston Moor. The north was now firmly in parliament’s hands and they weren’t to let it go.

Meanwhile, the armies under the Earl of Essex and Sir William Waller had moved on the Royalist capital of Oxford, in an attempt to bring the king to battle and defeat his army.

Charles expertly slipped out of Oxford with his army while the noose was closing, and in the end, Essex’s and Waller’s forces split. Essex marched south to relieve the port town of Lyme (currently besieged by Prince Maurice), and Waller was ordered to follow Charles, which eventually led to the defeat of Waller’s army at the Battle of Cropredy Bridge.

Charles then headed south with an army to put a stop to the Earl of Essex’s attempts to take Cornwall; this was achieved in great style at the Battle of Lostwithiel. Essex was caught between the West Country royalists and the king’s own army and lost all his infantry in the fight, effectively destroying one of the main parliament armies. Although the king had defeated two of parliament’s armies in the Midlands and south, it was not enough to counter the loss of the north.

Attempting to capitalize on their success at Marston Moor, the northern parliament army moved south to join Sir William Waller and a new army put in the field by the Earl of Essex. (Persistent he certainly was!) The aim was to combine and break the Royalist cause once and for all.

Luckily for Charles, the Scots had moved back north to deal with the Royalist army of Montrose that was making a nuisance back home, and so could not add their numbers to another inconclusive battle at Newbury (unimaginatively called Second Newbury), and the king could retreat once more to Oxford for the winter.

Checkmate

In April 1645 Parliament passed the ‘Self Denying Ordinance’, a law that meant that Members of Parliament could no longer take command of the armies. There were to be two exceptions to this law: Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell. The rationale of the law was to pave the way for a more professionally raised and commanded army, a ‘new modelled army’.

The New Model Army was initially formed by combining the forces of Essex, Waller and the Earl of Manchester, now forbidden to command. Parliament at last had the beginnings of an army that could bring the war to an end.

Despite these three armies being drawn together, due to heavy losses the previous year there were still shortages in manpower. Recruitment once more went into overdrive, particularly in London and South-East England to fill the ranks, so the New Model Army was by no means yet the finished article.

Contrary to popular belief not all of Parliament’s eggs were in one basket as there were a number of armies still in the field unaffected by the Self Denying Ordinance, although over time these were amalgamated into the New Model Army. Led by Fairfax, with Cromwell as deputy commander (and Commander of Horse), this army was to prove crucial.

Fairfax led his newly formed army to the Battle of Naseby where the Royalist Oxford army, led by King Charles himself, was routed in June 1645. From this point the First Civil War was a series of small scale battles and sieges leading to complete victory for Parliament. In March 1646 the last pitched battle was fought at Stow-on-the-Wold which was another in a long line of New Model Army successes.

King Charles surrendered to the Scots at Southwell, near Newark on 5th May 1646. He believed that the Scots could be bargained with, as he had at the end of the Bishops’ Wars. This was not to be, and he was handed over to Parliament, which effectively ended the war. The last Royalist garrison, that at Harlech Castle in Wales, finally surrendered on March 13th, 1647.

To Kill a King!

168 pages of colour-rich information with an introduction by writer Charles Singleton, this supplement for Pike & Shotte describes the history, armies, personalities and battles of the English Civil War. Included are detailed scenarios based on some of the most famous battles, complete with maps and orders of battle/army lists for the main protagonists.

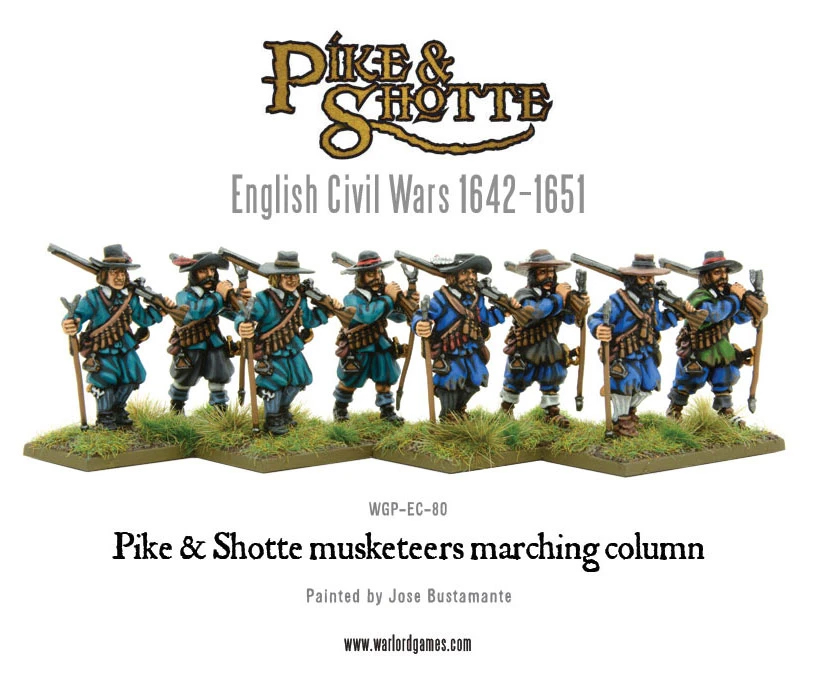

Musketeers

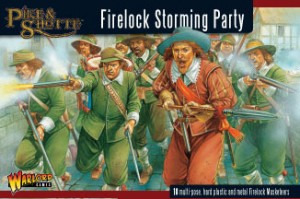

By popular demand we have made the ‘Pike & Shotte Musketeers Marching Column’ available again on the Warlord Webstore! The musket was the increasingly important infantry weapon at the time of the English Civil Wars. Individually, it was heavy, inaccurate and unreliable. Used en masse and by a proficient body of soldiers, its effect, as seen at battles such as Inverlochy, could be devastating. Most infantry were armed with the musket, which were in turn protected from the cavalry by the accompanying pike.

Check out the full English Civil Wars range!