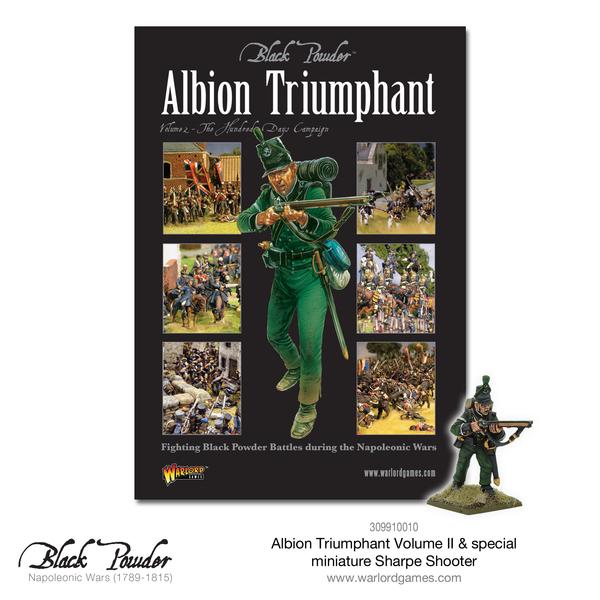

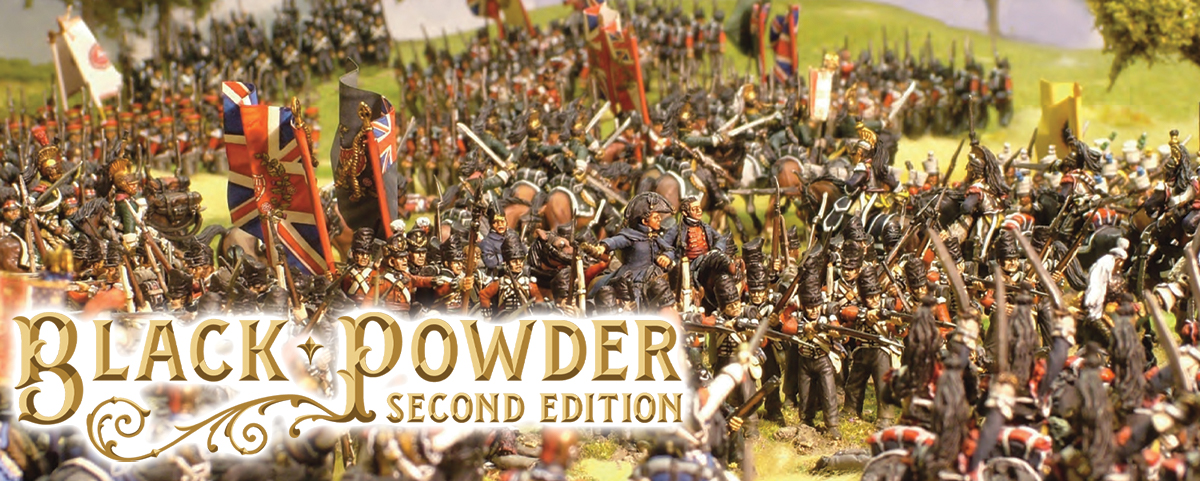

The Hundred Days and the famed battle of Waterloo marked the end of the First French Empire. You can refight the campaign using the Black Powder rules, in conjunction with Albion Triumphant Volume 2.

Returned from Exile

The shattering of the Grande Armèe in the snows of Russia in 1812, followed by two years of desperate fighting, forced the Emperor of the French to abdicate in 1814. The Sixth coalition exiled Napoleon to the tiny island of Elba. He would not be confined there long.

Sailing forth on the flagship of the Elban Navy, Napoleon slipped his leash intent on regaining his throne. His spies informed him of dissatisfaction with the Bourbon regime and many flocked to his renewed cause. Many sent to catch and imprison him were quick to change sides and pledge their support. Prisoners of war in particular; recently returned to France; provided his forces with some battle-hardened veterans.

In March 1815, Napoleon entered Paris at the head of his army, accompanied by several of his trusted Marshals. He hoped that his meteoric rise to power would bring the great powers of Europe to the negotiation table, too war-weary to risk fighting yet another costly campaign against a proven French army. Unfortunately, it was not to be, and the newly-formed Seventh Coalition declared Napoleon an outlaw on 13th March, followed swiftly by a declaration of war.

The Seventh Coalition quickly assembled a mass of 700,000 men on the borders of France, intending to repeat the invasion plan of 1814, defeating the French with sheer weight of numbers. Napoleon for his part was quickly able to assemble 500,000 men to fight under his own banner.

Wellington’s army was a shadow of the grand force he had led to victory in the earlier Peninsular campaigns, those forces having been broken up to confront the USA on the far side of the Atlantic. He lacked veterans and seventy per cent of his infantry was not comprised of British citizenry; many of its battalions untested or formed of variable quality Belgian, Dutch and German contingents. The Prussian army too appeared to be fragile. Napoleon devised his plans…

A Swift Strike

With his enemies amassing all around, Napoleon decided to launch a pre-emptive strike against a Prussian and a British army assembling in Belgium. On 15th June, his army rampaged across the Belgian border, sweeping aside the Prussian pickets at Charleroi. Victory depended on swiftness before the Coalition could react and amass a concentration of force. He would need to defeat each opposing army before they could merge into a far more threatening force.

Expecting a characteristic flank attack, the Coalition forces were covering the good roads towards Mons. Having identified the weakness between the British and Prussian armies, Napoleon divided his force into three groups, with the left wing under Marshal Ney advancing towards the crossroads at Quatre Bras, while Napoleon and Marshal Grouchy took the fight to the Prussians at Ligny.

Blucher’s Prussian corps were arrayed along the road to the east of Quatre Bras, standing ready to repulse the right and centre wings of Napoleon’s advancing army. From the beginning, Blucher was counting on Wellington to cut through the opposition at Quatre Bras and take the attacking French in the flank, ultimately pinning and destroying Napoleon’s army.

“Napoleon has humbugged me, by God; he has gained twenty-four hours’ march on me.” – The Duke of Wellington.

Wellington was caught off-guard by Napoleon’s attack, however, having received the word of Prussian attacks a full six hours after battle had been joined. With the bulk of the Coalition army either engaged at Ligny or on the march, they were left with a single division facing down three French infantry divisions and a cavalry brigade.

Waterloo

British success at Quatre Bras was undermined by the Prussians‘ failure to hold the line at Ligny. Wellington’s army was forced to fall back northward. Marshal Ney, having failed to win the crossroads at Quatre Bras had been slowed, allowing Wellington to pick his ground for the next clash. That ground would be Waterloo two days later.

With time granted to them by the good order of their retreat, Wellington was able to organize one of his characteristic defensive battles, occupying the high ground, commanding a dominating position that withstood numerous frenzied charges on the position – from the most elite of the French Cavalry and assaults from the French Imperial Guard.

The Prussian army arrived on Napoleon’s flank during the afternoon, and the tide of the battle was ultimately determined. The combined armies swept the French from the field of Waterloo, with the victory effectively putting an end to both the First French Empire and the Napoleonic Wars.

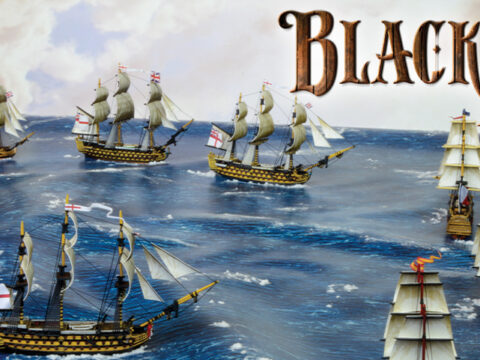

Lion meets Cockerel in Climactic Battle

The violent and bloody conclusion of the clash between two of history’s greatest generals, Wellington & Napoleon, occurred on an unassuming rain-soaked Belgian field on 18th June 1815. All this is detailed in Black Powder supplement, Albion Triumphant Volume 2. Providing a deeper exploration into the specifics of Napoleonic era and what sets it apart from other periods of horse and musket warfare, this supplement focuses on the climactic clashes of the Hundred Days Campaign, leading up to what many consider to be the most famous battle in all of military history, Waterloo.

Volume Two covers the Hundred Days campaign culminating in the grand clash at Waterloo (June 1815), and includes army lists and profiles for all the major participants. A separate volume focuses on the earlier campaigns of the Peninsular War.

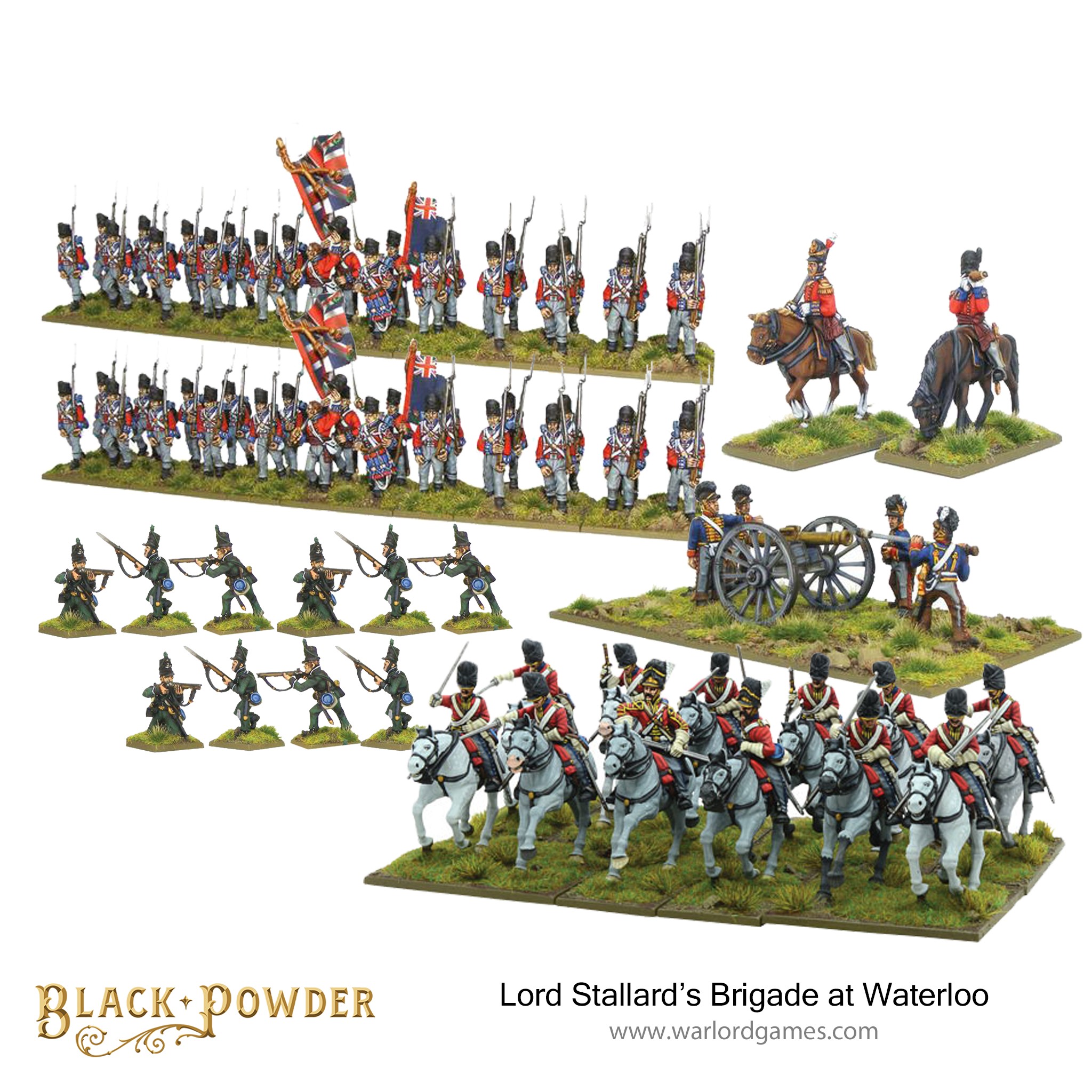

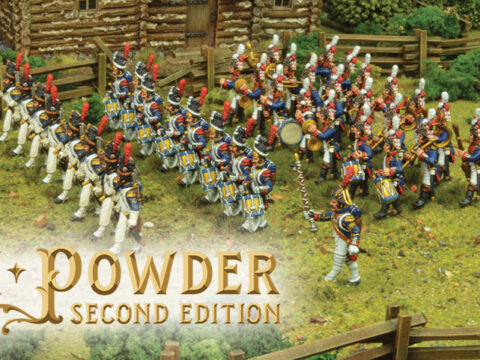

British Forces

During the Peninsular Campaign, the British had excelled, whether attacking or defending, but they were unbeatable when they were formed on the reverse slope of a ridge. this defensive tactic had ensured that many French commanders were wary of attacking the English battle line. wellington took great care to shelter his lads out of sight of the enemy and with secure flanks. He would line the crest with his artillery and throw out large numbers of skirmishers onto the forward slope to contest the French, advancing to the ‘pas de charge’ drum beat, or ‘old trousers’ as the British called it. the enemy, unsure as to the location of wellington’s main force, more often than not had blundered into British lines without being in the correct formation for the tactical situation. they would then be thrown into confusion by close-range volleys whilst trying to deploy, and a loud cheer would signal a controlled bayonet charge that would sweep the disordered French away. the Hundred Days campaign would see these tactics tested to the limit, some French commanders having learned from their mistakes on the Peninsula.

Contains:

- 72 Plastic and metal British Line infantry in Belgic Shakos

- 24 Plastic and metal Hanoverian infantry

- 12 Plastic and metal British Union Brigade heavy cavalry

- Officer on horse

- Royal Horse Artillery 9-pdr cannon

- Full-colour flag sheets

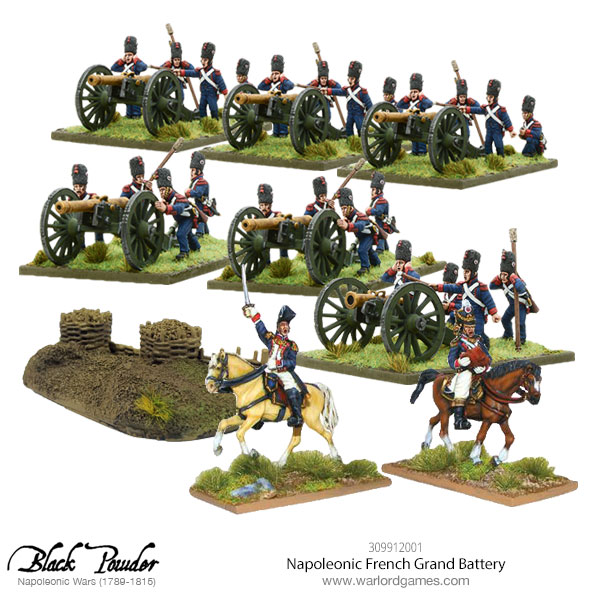

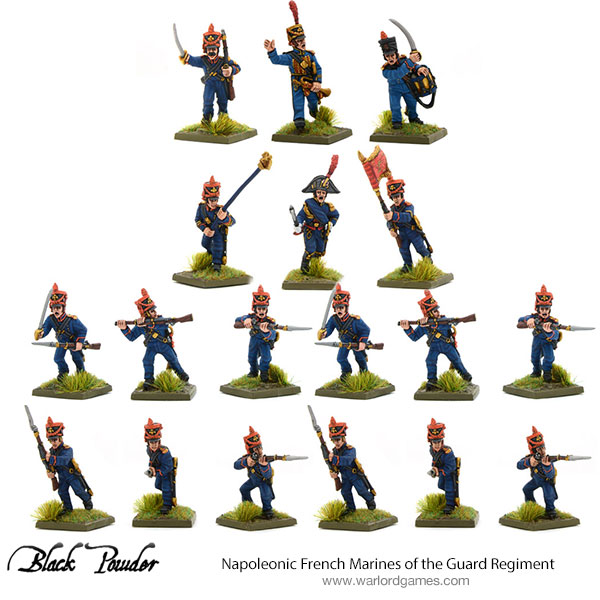

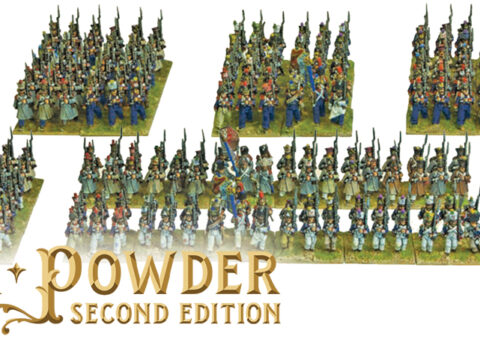

French Forces

As a result of the campaigns of the Peninsular War and the Russian campaign, the decline in the raw material of the army, the common french infantryman, meant that they were now increasingly less skilled in battlefield drill. The reliance on fast-moving assault columns, driven on by the pas de charge, became more emphasised. attacking in column would force results quickly on the field, especially if supported by a massive artillery bombardment. in all his campaigns napoleon had searched for the decisive battle that would win the war at a single stroke. The waterloo campaign would certainly emphasise this by the manoeuvres to isolate the allied armies. The divisional columns of D’Erlon’s I Corps, attacking on the field of waterloo, and the Grande batterie’s barrage, were all a product of what had gone before.

Contains:

- 84 French Line infantry

- 28 French Light infantry

- 12 French Line Lancers

- Officer on horse

- 6-pdr cannon

- Full-color flag sheets

- Waterslide decal sheets